After many, many years, I recently played Subbuteo again. It was such a blast that I’m starting a series of posts on the world’s greatest football game ever invented. My older brother, who taught me how to play, kicks off.

By Daniel Alegi

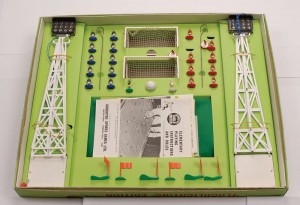

Rome, Italy, Christmas 1973: I finally got Subbuteo, the new English game everyone was talking about. It was the “Continental” set (see photo below); the box said the name was pronounced “sub-BEW-teo.” 20,000 lire ($15) got you a green cloth pitch, two white floodlights 13 inches high with 9-volt batteries, two plastic goals with brown nets, two balls, two goalies with a handle-rod and two teams in white shorts: one with red shirts, the other with blue.

“Italy – Russia!” I said. “Como-Varese!” said my brother from the height of his 18 months’ seniority. Their kits are almost identical, but would you rather make your debut in the Christmas snow at Moscow’s Lenin Stadium or in a Serie B derby in the Po Valley fog? Our first flicks were backed by our grandfather in the armchair snoring away. Cloth pitch on the carpet, improvised rules. Then during lunch dad stood up and stepped on everything (how could he miss a 4.5ft x 3ft pitch?). On the ground lay decapitated, amputated, crushed players. Only six survived this massacre, one of them a goalkeeper. And so with this ill-fated 1973 debut, played with only one goal, Subbuteo entered our house forever.

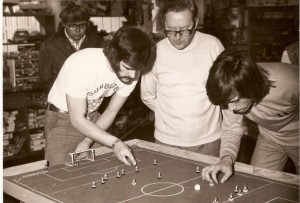

The “Club Calcio in Miniatura Subbuteo” (Cicms) was among the first Subbuteo clubs in our neighborhood. My older brother was the chairman, a neighbor who played with his legendary Red Star Belgrade and I were the other members. Later some more friends joined. The green cloth went from the floor to a plywood board on trestles. We played with the small, orange ball, the one the “professionals” used, or so we thought.

Official tournaments followed, the first in a church basement in Piazza Verbano. Four tables in a row; referees, briefcases, the air of true professionalism. We play with the large ball, what the Cicms called “beginner”, and in silence. Experienced players made their Subbuteo figures slide—miraculously—in a straight line. Ours curved around defenders to get to the ball, but could not slide smoothly across the pitch. Losing by substantial margins taught us the importance of “treating” the bases with furniture polish. This had a radical impact on our game. Suddenly we could kiss the ball with a flick from the defensive back line and then be able to shoot at goal with two touches. A wonderful discovery! The names of our teachers were Filacchione and Di Politica. Their Subbuteo was definitely not a miniature version of football: the teams often had white jerseys, no numbers. No one looked at the number of the goalscorer, as we did in our friendly competitions at home. This sport was for adults.

The Italian champion that year was Stefano Beverini from Genoa (at right, vs Mike Dent, 1975?). Almost 30 years old, beard (it was the 70s!), he appeared in the Italian Subbuteo national team jersey in the official Parodi catalog. He traveled around the country by train to show off his perfect chip shots and long-distance flicks in lobbies of luxury hotels. I went to the Hotel Parco dei Principi to see this phenom who had come in third at the 1974 Subbuteo World Cup. But there were way too many people there and the table was too far away. On TV that evening they showed two goals he scored from free kicks expertly chipped over the wall. Very difficult. Beautiful stuff.

The Italian champion that year was Stefano Beverini from Genoa (at right, vs Mike Dent, 1975?). Almost 30 years old, beard (it was the 70s!), he appeared in the Italian Subbuteo national team jersey in the official Parodi catalog. He traveled around the country by train to show off his perfect chip shots and long-distance flicks in lobbies of luxury hotels. I went to the Hotel Parco dei Principi to see this phenom who had come in third at the 1974 Subbuteo World Cup. But there were way too many people there and the table was too far away. On TV that evening they showed two goals he scored from free kicks expertly chipped over the wall. Very difficult. Beautiful stuff.

Our neighborhood club slowly declined. We continued using the small ball because the goals seemed more spectacular that way. Our bases were rough and repainted whereas Beverini and other “pros” used exclusively white bases. My younger brother, Peter, began to play. We made some of our own rules, which was fun but distanced us from top-flight tournament play. (This was typical as Subbuteo rules were often changed ad hoc.)

Freshman year in high school, my classmate Rossi and I began using silicone-based Nugget polish to “treat” our teams in hotly contested after-school matches at his house. Our game exploded. We made our guys slide the length of the pitch to connect with the ball, a move that became my specialty. Our tactical formation featured seven defenders in a straight line, a Maginot Line that the attack was forced to “unlock” by quickening the pace and provoking the defense into a “back” violation (the defensive blocker collides with the attacker before the latter touches the ball). We went to Zorzi’s place for the first time: he was a Subbuteo professional and a collector of “Playboy.” We played doubles (2 v 2), 15 minutes halves, Zorzi and I against Rossi and Piscitelli. We played close and quick: 3-0 to us. Zorzi was surprised: “You guys are good; are you coming to the regionals?”

“Guerin Subbuteo” tournament (named after its sponsor — Guerin Sportivo, Italy’s oldest football weekly): in a huge toy shop near my grandmother’s house. 100 participants, 20 tables, anxious mothers, and the smell of furniture polish. I was playing with my new Hamburg side, freshly painted: blue shirts and light pink bases, white numbers. Not great for chip shots, but precise for long-range flicks. I won all my matches without conceding a goal (11-0, 8-0, 5-0 etc..) and earned a spot in the quarter-finals against . . . Zorzi. With the crowd on my side, I gave battle but lacking in experience I lost 1-0 in extra time. OSL (Organizzazione Subbuteo Lazio) and ASR (Associazione Subbuteo Roma) — the two best clubs in the city — both recruited me, promising various benefits and sponsorships. I joined OSL simply because I needed a club closer than ASR, which was way out in the Portuense area.

“Guerin Subbuteo” tournament (named after its sponsor — Guerin Sportivo, Italy’s oldest football weekly): in a huge toy shop near my grandmother’s house. 100 participants, 20 tables, anxious mothers, and the smell of furniture polish. I was playing with my new Hamburg side, freshly painted: blue shirts and light pink bases, white numbers. Not great for chip shots, but precise for long-range flicks. I won all my matches without conceding a goal (11-0, 8-0, 5-0 etc..) and earned a spot in the quarter-finals against . . . Zorzi. With the crowd on my side, I gave battle but lacking in experience I lost 1-0 in extra time. OSL (Organizzazione Subbuteo Lazio) and ASR (Associazione Subbuteo Roma) — the two best clubs in the city — both recruited me, promising various benefits and sponsorships. I joined OSL simply because I needed a club closer than ASR, which was way out in the Portuense area.

During a hiatus in 1981, when I went to the US as an exchange student, Rossi wrote to tell me of Zorzi’s tragic death, run over by a speeding car in Viale Parioli. After returning to Rome I resumed my life on the green cloth. I began to play with Max Marcaccini, another classmate, who reignited the pleasure of playing for pure fun. We ate lunch daily at his grandmother’s, and then played the English League, the Italian Cup final, and so on.

I kept playing competitively and my OSL teammates taught me skills like the secret art of goalkeeping: looking at the index finger of your opponent, not the ball. Pascoli always wanted to bet on our games. Once I won his Arsenal team with white bases that had once belonged to Scaletti, a top-ranked player. The bases were larger than average, making it more difficult for the opponent to attack; the plastic was more dense, making chip shots virtually unstoppable. This particular Arsenal probably came from those rumored “manufacturing defects” that one had to scavenge for in the shops.

I started digging through the Subbuteo team boxes at the old lady’s shop in Piazza Vescovio, searching for deformed white bases (you could not modify the bases, but it was acceptable to use variants of the factory products). The collection of trophies at mom’s house grew before our eyes.

I started digging through the Subbuteo team boxes at the old lady’s shop in Piazza Vescovio, searching for deformed white bases (you could not modify the bases, but it was acceptable to use variants of the factory products). The collection of trophies at mom’s house grew before our eyes.

I met Mancini in Naples: he painted teams with insane details. My 1982-83 Juventus had players with Puma, Adidas, and Patrick shoes; Boniek wore his good-luck necklace, Gentile had curly hair, Bonini’s was blond. My beloved Fluminense (red and green stripes, with heavy yellow bases) was jaw-droppingly fantastic. These were the only two teams I used in those years.

Afternoon “workouts” with OSL consisted of games in little rooms with grannies sitting silently in the hallways knitting, family dinners, and kids outside playing soccer. I religiously logged every game in a special notebook: date, place, type of competition (friendly, tournament, etc.), score, and opponent (with updated record vs. that opponent). I practiced to improve the weakest aspects of my game: the chip shot and goalkeeping. By this time my older brother had long abandoned Subbuteo, but my younger brother (by 5 years), Peter, had become very good in the under 16 category. When he kept his cool and did not protest, he won official tournaments and traveled with me by train to Terni, Ancona, Pescara, Milan, to Veneto and often Liguria for nationals.

Genoa, National Championships. Palazzo dello Sport, the city’s indoor arena, with American football being played in the main arena (with cheerleaders) and Subbuteo in the main concourse. Peter, Lazio region junior champion, lost to the Italian champion, a younger boy from Calabria. Lacking in fair play, he walked away in disgust. Too bad. As for me, I was drawn in a mediocre group in the first round, but lost against the Umbria champion who also accused me of having parried a shot with my hand. I finished seventh. The evenings were nights out in Caricamento, the gritty area around Genoa’s harbor, eating pizza and chasing girls. On the long train ride back to Rome, Presutti taught me how to solve Rubik’s Cube.

1982. I qualified again for the national championships in Alassio, near Genoa. As luck would have it, the Italian national team was doing its pre-World Cup camp there, so we were able to take pictures with the future World champs. Zoff, Oriali, and Marini came by to congratulate us. I qualified for the second round, despite losing 3-8 against Renzo Frignani, the Subbuteo world champion. Against Ogno from Cagliari I collapsed in the final two minutes: from 2-1 to 2-3; arguing with the referee was not my style, but the “back” he awarded against me was ridiculous. Ogno took advantage and chipped me to draw level. A minute later he put the dagger in. Having failed to qualify for the semi-final, I won the final for 7th place, again. Frignani earned another Italian title. The following month he also won the world title in Barcelona. His secret was to mark the ball more closely, without ever committing a “back” and never allowing the attack to advance in a straight line against his dynamic defense.

1982. I qualified again for the national championships in Alassio, near Genoa. As luck would have it, the Italian national team was doing its pre-World Cup camp there, so we were able to take pictures with the future World champs. Zoff, Oriali, and Marini came by to congratulate us. I qualified for the second round, despite losing 3-8 against Renzo Frignani, the Subbuteo world champion. Against Ogno from Cagliari I collapsed in the final two minutes: from 2-1 to 2-3; arguing with the referee was not my style, but the “back” he awarded against me was ridiculous. Ogno took advantage and chipped me to draw level. A minute later he put the dagger in. Having failed to qualify for the semi-final, I won the final for 7th place, again. Frignani earned another Italian title. The following month he also won the world title in Barcelona. His secret was to mark the ball more closely, without ever committing a “back” and never allowing the attack to advance in a straight line against his dynamic defense.

The following year, in the Italian Cup (a club competition with a format similar to the Davis Cup in tennis), my teammate Fabrizio Sonnino, tired of the crowd’s anti-Semitic comments, broke someone’s nose. We left there and then, having already won enough matches to qualify for the final in Rome. In the semifinal we met Frignani’s club from Reggio Emilia and that was that. We claimed third place. The gym where we played was really small and cramped, the organization had become a bit haphazard.

In another tournament I had to deal with an opponent who used a modified goalie rod that featured a welded extension cord that fit snugly at the intersection of the crossbar and post! I lost to the trickster in the finals, taking home yet another small trophy and continued to update my log book (with well over 1,000 games). Subbuteo was the only true sport for me. In September 1983, I left for four years of college in America, and my brother Peter carried on the family tradition for a while, until he too moved on.

(“Memories of a Subbuteo Player” is adapted from a piece published in GiocArea, June 1998. Translated by Peter Alegi. My thanks to Andrea Angiolino for sending the original article.)

Categories

4 replies on “Memories of a Subbuteo Player”

Long piece from the Guardian (2011): http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/blog/2011/jul/23/subbuteo-football-sport

Ciao Danny, ciao Peter,

bellissimo il pezzo sulle memorie subbuteistiche, complimenti davvero!

E mi ha fatto enormemente piacere leggere che tra i tanti ricordi, avete pensato anche a Gianluca, che purtroppo non c’è più da tanti anni.

Proprio pochi minuti fa mia madre è tornata a Roma da Trieste, e mi ha consegnato alcune foto dell’82 scattate durante la fase finale del Guerin Subbuteo (credo) in cui appare anche Danny.

Mi sono messo a cercare sul web l’albo d’oro di quei campionati e tra i pochi link disponibili c’era questo, che mi ha riportato a voi.

Mi farebbe immensamente piacere risentirvi !

Un abbraccio

Maurizio

Why Subbuteo Remains a Cherished Childhood Memory:

http://www.balls.ie/football/subbuteo-remains-a-cherished-childhood-memory/299278

Ciao Caro Danny! Bellissimi ricordi legati al nostro caro Subbuteo. Quando venivo a casa vostra giocavo con Peter e utilizzavamo proprio la juve e il Fluminense, che squadre meravigliose! Il sottofondo delle nostre partite (insieme anche a Sokolivic) erano i Dire Straits con Brothers in arms e anche Circo Massimo di Antonello Venditti, ricordo anche Billy

joel. Grazie per questo bel racconto! Un grande abbraccio a te e a Peter!