Alexandra Wrage, a Canadian attorney and founder of TRACE International, a business anti-corruption group, was interviewed by BBC Newsnight about the ongoing FIFA corruption scandal over Qatar’s successful bid to host the 2022 World Cup.

Alexandra Wrage, a Canadian attorney and founder of TRACE International, a business anti-corruption group, was interviewed by BBC Newsnight about the ongoing FIFA corruption scandal over Qatar’s successful bid to host the 2022 World Cup.

Wrage worked for FIFA’s governance reform commission from 2011 to 2013. In April 2013 she told the Wall Street Journal “that the FIFA executive committee ‘undermined the recommendations we were making’at almost every turn.” She resigned because “you don’t keep doing the same thing if you’re not having an impact.”

Wrage believes change is more likely to come if Swiss law regulates locally based non-profits like FIFA (sic!) more effectively and, perhaps, if a groundswell of popular criticism can compel corporate sponsors to take action.

Click here to watch the 4-minute interview.

Author: Editor

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

“If you want to see the heart of China’s soft-power push into Africa,” writes Elliot Ross in a recent piece for Sports Illustrated’s “Roads & Kingdoms” series, “you’ll find it in the continent’s new soccer stadia.”

I am one of the many Zambians saddened that most of our national team matches are now staged at the Chinese-built Levy Mwanawasa Stadium in Ndola, an industrial town on the Copperbelt 200 miles north of the capital, Lusaka. This is not only because I live in Lusaka, where the team used to play its home games, but also because the move greatly diminishes, if not erases, the deeper significance of historic football venues.

It was in Lusaka’s then-newly constructed Independence Stadium on October 23, 1964, that the Union Jack was lowered and the new Zambian flag raised at midnight in a sumptuous ceremony attended by the Princess Royal and Kenneth Kaunda’s new cabinet. The following day, the stadium hosted the final of the Ufulu (independence) tournament. Ghana’s Black Stars, reigning African champions, beat Zambia 3-2 in front of about 18.000 spectators. From then on, almost all important international matches (as well as domestic cup finals) were played at Independence Stadium, a local example of how stadiums in postcolonial Africa, “quickly became almost sacred ground for the creation and performance of national identities” (Alegi, African Soccerscapes, p. 55).

Occasionally, Dag Hammarskjöld Stadium in Ndola hosted big matches. Constructed by the Ndola Playing Fields Association during the colonial era, this ground was rechristened in honor of the Swedish Secretary-General of the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjöld, who died in 1961 in a plane crash near Ndola. After the British colony of Northern Rhodesia became independent Zambia, the stadium was donated to the Ndola City Council. As the largest stadium in the Copperbelt, the traditional hub of football in the country, it hosted virtually every important match in the region.

In January 1986, the Zambian government bought into the idea of hosting the 1988 African Nations Cup finals. Mary Fulano, then a member of the Central Committee in charge of sport, informed the public that the government had started renovating both Independence and Dag Hammarskjöld stadiums. But in December 1986, after Dag Hammarskjöld stadium had been demolished for its planned reconstruction, Youth and Sport minister Frederick Hapunda announced that government had withdrawn its bid to host the 1988 tournament.

Copperbelt residents complained that they needed their beloved stadium, but the government kept on issuing empty promises. Surprisingly, two decades later, when an opportunity arose to build a new stadium in Ndola courtesy of China, the Zambian government opted for a completely new Levy Mwanawasa Stadium in a different area, thereby burying the rich history of Dag Hammarskjöld Stadium.

In 2012, I attended the inauguration of the Levy Mwanawasa Stadium: a 2014 World Cup qualifier between Zambia and Ghana (see my blog post about it here). The atmosphere at the venue was similar to the one described by Elliot Ross at the Estádio Nacional do Zimpeto in Maputo. Unlike the game in Maputo, however, there was no pushing and shoving at Levy Mwanawasa, thanks to plenty of available space and sound event management. But the stadium was so vast that the crowd could not sing and chant cohesively, or create the electrifying atmosphere so many of us treasure at football grounds.

The ignominuous end for Independence Stadium in Lusaka came after FIFA inspectors in 2007 declared it unsafe for international matches. As a temporary solution, the Football Association of Zambia moved internationals to Nkonkola Stadium in a small mining town on the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo. Bolstered by another Chinese loan, the Zambian government then erected a new National Heroes Stadium directly across from Independence Stadium and the graves of national team members who perished in the Gabon air crash of 1993.

The demolition of Independence Stadium prompted many people to wonder why the government chose not to renovate the hallowed ground and build the Chinese-funded stadium somewhere else in Lusaka. While younger Zambians tend to like the new sporting arenas, many older fans lament the disappearance of stadiums they associate with the stories of their personal lives, their memory, their past.

Regardless of age and status, Zambians are very much aware of “Chinese soft diplomacy.” People know that Chinese stadiums have less to do with friendship or mutual cooperation and more with gaining access to Africa’s material resources. Yet there is very little that can be done about it because the government does not consult with citizens on economic deals with China. There is criticism about Chinese firms bringing very cheap laborers to work in construction sites. But there seems to be a general feeling among the population that it is acceptable for the Chinese to build stadiums and other infrastructure in exchange for copper because the alternative is allowing Zambia’s political leaders to pocket the profits from this wealth.

—

*Hikabwa Chipande is a PhD candidate in History at Michigan State University. He is a recipient of the FIFA Havelange Research Scholarship for his doctoral dissertation on the social and political history of football in Zambia, 1950-1993. Follow him on Twitter at @HikabwaChipande

The Football Scholars Forum, an international online think tank, convened on November 14 to discuss Football in the Middle East. The conversation focused on a special issue of the academic journal Soccer and Society, edited by Alon Raab and Issam Khalidi. The group began by noting that while football has been a critical force in broader political and cultural developments in the region, there is little institutional support for studying the game in the Middle East.

The Football Scholars Forum, an international online think tank, convened on November 14 to discuss Football in the Middle East. The conversation focused on a special issue of the academic journal Soccer and Society, edited by Alon Raab and Issam Khalidi. The group began by noting that while football has been a critical force in broader political and cultural developments in the region, there is little institutional support for studying the game in the Middle East.

The ensuing 90-minute discussion demonstrated the value of scholarly collaboration and research on the game. The group explored a dizzying number of topics and territories, including football as a source of unity and hope and as a site of political and ideological conflict; the 2022 World Cup in Qatar; soccerpolitics in Turkey; sport and Islamism; Palestinian and Iraqi Kurdish women’s teams; and football films and poetry.

For a Storify Twitter timeline click here.

Download the mp3 of the session here.

Guest Post by Khaya Sibeko (@KhayaSibeko1)

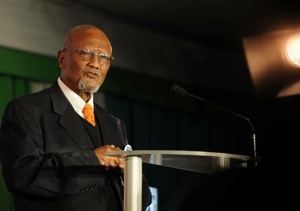

JOHANNESBURG—On October 30, 2013, Leepile Taunyane, South Africa’s legendary football administrator, died at the age of 85. It would not be an exaggeration to compare his passing to the burning of a national archive.

Born in Alexandra, Johannesburg, Taunyane grew up playing football in the streets and then joined Rangers in the early 1950s, a club known for its technical prowess and feared for its lineup stacked with ex-convicts. After hanging up his boots, in the 1960s Taunyane started a career as a football organizer and served as principal first at Alexandra High School and then at Katlehong High.

His administrative career saw him involved in every major transformation in the South African game. Taunyane worked with Bethuel Morolo at the South African Bantu Football Association and then with his successor, George Thabe. In the mid-1980s, an era of massive political and social upheaval in apartheid South Africa, Taunyane led the Transvaal affiliate of Thabe’s Africans-only organization to throw its weight behind the National Soccer League. A precursor of today’s Premier Soccer League, the NSL was a new, racially integrated league launched in 1985 as a break away league from Thabe’s NPSL. Taunyane became the NSL’s first president.

In a recent City Press article, Premier Soccer League and Orlando Pirates chairperson, Irvin Khoza honored his mentor: “I was his student when he was a teacher. He recruited me at the tender age of 14 to become a member of the Alexandra Football Association. We later rubbed shoulders in the national league and federation structures. Dr. Taunyane personifies the values that govern my decision-making and actions, consciously and unconsciously.”

Taunyane was “the last of the Mohicans” of football administrators of a venerable generation. Even when others around him found the temptations of post-isolation football too much to resist, Taunyane remained a diligent and incorruptible servant of the beautiful game. It was no surprise when, a few years ago, the PSL bestowed the honorific title of Life President.

It is not enough to celebrate and award titles, of course. By publicly recognizing Taunyane’s great legacy, local football administrators should strive to follow his exemplary managerial conduct. That would be the best way to remember and honor a “son of the soil” who spared neither time nor energy in the service of football and education.

Undoubtedly, the gods of South African football have placed Taunyane alongside Bethuel Mokgosinyane, Solomon Senaoane, Dan Twala, Albert Luthuli, Henry Ngwenya, George Singh and so many elders of the distant past, men whose efforts shaped our football in the era of segregation and apartheid. Without the contributions of men like Taunyane, South Africa would never have hosted the 2010 World Cup and the PSL would not be among the ten richest leagues in the world.

Guest Post by *Hikabwa D. Chipande (@HikabwaChipande)

LUSAKA––The Football Association of Zambia and Hervé Renard have parted company after the 2012 African Nations Cup winning coach signed with French Ligue 1 club Sochaux. FAZ communications officer Eric Mwanza made the announcement on Monday (October 7) after much speculation that the Frenchman was on his way out. Rumors had been flying around Lusaka that the Frenchman was interviewing for jobs overseas. He had also hinted a few months ago before the Zambia vs Ghana 2014 World Cup qualifier that if the team were to fail to make it to Brazil then he’d resign.

LUSAKA––The Football Association of Zambia and Hervé Renard have parted company after the 2012 African Nations Cup winning coach signed with French Ligue 1 club Sochaux. FAZ communications officer Eric Mwanza made the announcement on Monday (October 7) after much speculation that the Frenchman was on his way out. Rumors had been flying around Lusaka that the Frenchman was interviewing for jobs overseas. He had also hinted a few months ago before the Zambia vs Ghana 2014 World Cup qualifier that if the team were to fail to make it to Brazil then he’d resign.

Although FAZ indicated it consulted with Renard and “agreed not to stand in his way,” many Zambians have received this decision with mixed feelings. Some wondered whether Renard had just managed to sweet-talk and dump the national team as he did in an earlier stint with Chipolopolo (copper bullets).

In 2008, Renard landed the Chipolopolo job after working as an assistant to his fellow Frenchman and mentor Claude Leroy, then head coach of the Ghanaian national team, the Black Stars. Renard led Chipolopolo to the quarterfinal of the 2010 African Cup of Nations, a result last achieved at the 1996 tournament in South Africa. In 2010, he left Chipolopolo for better paying Angola, but was soon fired after going four games without a win. After Angola, Renard moved on to coaching USM Alger.

Following the dismissal of Italian coach Dario Bonetti, the Football Association of Zambia announced on October 22, 2011, that Renard would return as coach of the national team on a one-year contract. Peter Makembo, patron of the Zambia Soccer Fans Association, seemed to speak for many local fans when he questioned the loyalty of the French manager. After hearing that Renard was being interviewed at FC Sochaux a few weeks ago, Makembo told Radio Ichengelo that, “as soccer fans we feel betrayed by Renard’s actions.”

However, Renard silenced all his critics in his second tenure at the helm of Chipolopolo by winning the 2012 African Nations Cup: Zambia’s first-ever continental crown. His charges dispatched favourites Senegal in the group stages and African powerhouses Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire in the semi-final and final respectively.

There is no doubt that Renard will remain one of the most respected and loved coaches in the history of Zambian football because of the African title he brought to the country. But some critics point out that he only came back when it suited him and that he reaped where he did not sow since Bonetti, whom he replaced, had done the groundwork for Chipolopolo’s success.

Other Zambians remarked that Renard came here as an inexperienced player and used Zambia to build his coaching resumè before leaving for greener pastures. This is a common phenomenon not only in African sport, but in donor-funded development projects too. Typically, “Western” volunteers arrive, are mentored by local men and women, and then return to their countries where they often become “experts” paid to supervise the Africans who originally taught them much of what they know.

The question remains: is there anything wrong in a European professional coming to an African country like Zambia to build his profile only to leave for a more prestigious, high-paying job? From my point of view, this is how things are and there is little we can do apart from getting used to it. We also need to be realistic and come to terms with the fact that inexperienced, ambitious coaches like Hervé Renard are what poorer countries like Zambia can attract and afford to pay. Few African nations can hire exaggeratedly expensive coaches like the Brazilian Carlos Alberto Parreira, as South Africa did for the 2010 World Cup. (Interestingly, South Africa became the first host nation in World Cup history to be eliminated in the first round of the competition.)

From 2010 to 2013, Renard proved that he is a good coach by delivering what all previous Zambian skippers failed to do: win the African Nations Cup. Many Zambians argue that he is the best foreign coach Zambia has ever had, sometimes in tandem with Yugoslav Ante Buselic who took Chipolopolo to second place in the 1974 Nations Cup in Egypt. Without question, Renard will remain close to the hearts of millions of Zambian soccer fans for a very long time.

However, the Frenchman’s failure to defend the African title and Chipolopolo’s premature elimination from the 2014 World Cup qualifiers compelled FAZ to part ways with Renard. Luckily for Zambia, Renard’s new employers rejected his proposal of bringing his assistant Patrice Beaumelle, also French, to Sochaux. As a result, Beaumelle was chosen as interim head coach of the national team.

Depending on how the new Frenchman will command the Chipolopolo during the friendly match against Brazil in China in a few days’ time, he is likely to be confirmed as Renard’s permanent replacement. Zambians hope that Beaumelle will perform the same miracle as his predecessor, even if he’s only here to strengthen his coaching pedigree before moving on to the next level of world football.

—

Hikabwa D. Chipande is a PhD student at Michigan State University. He is currently in Lusaka conducting archival research and oral history interviews for a doctoral dissertation on the social, cultural, and political history of football in colonial and postcolonial Zambia. Follow him on Twitter: @HikabwaChipande

By Bruce Berglund (cross-posted from @NewBookSports)

By Bruce Berglund (cross-posted from @NewBookSports)

In 2010, for the first time, an African nation hosted the FIFA World Cup. The advertisements surrounding the tournament used graphics and sounds intended to conjure the image of a vibrant, exotic land. In fact, though, the African-ness of the South African World Cup was pretty thin, when not wholly fabricated. For example, the music that introduced ESPN’s World Cup coverage sounded very African, as it opened with the sounding of an ox horn (the promo showed a bare-chested tribesman blowing the horn atop a mountain, silhouetted against the setting sun) and then built with pulsing drums and a choir singing layered refrains. But the piece had been written by a composer from Utah, the musicians had recorded it in Utah, and the choir consisted of members of the Broadway cast of The Lion King. At least Shakira’s ubiquitous song “Waka Waka (This Time for Africa)” had a more substantial African connection. It had been lifted, initially without credit, from a Cameroonian military song made popular in the 1980s by the group Golden Sounds.

The ironies of the 2010 tournament in South Africa are revealed in a number of essays in Africa’s World Cup: Critical Reflections on Play, Patriotism, Spectatorship, and Space (University of Michigan Press, 2013), edited by Peter Alegi and Chris Bolsmann. In the interview with Peter, we learn of the findings and observations of the volume’s contributors: an international collection of anthropologists, architectural critics, bloggers, geographers, sociologists, journalists, photographers, and former players who all attended matches in South Africa. They make sharp criticisms of class divides at the venues, the nationalism and commercialism, and, of course, the imperial reach of FIFA. But as we hear from Peter, the book’s authors were also fans. When mixing with other fans outside the stadiums, and then cheering their teams when the matches began, even normally skeptical academics and journalists were caught up in the event. Their experiences show that, for all its faults, the FIFA World Cup is still an incomparable event.

Click here to download the mp3 of the interview.

A “Hallmark Holiday” for American Soccer

Guest Post by Tom McCabe

I’ve been invited to not one, but three Boxing Day parties this year, which got me thinking that the day after Christmas should become a soccer holiday in the United States. Like other manufactured holidays such as Grandparent’s Day, Secretary’s Day, and Boss’s Day, Boxing Day can become American soccer’s Hallmark Holiday.

This country has no real tradition for December 26th, unlike England and some other Commonwealth countries, so two Englishmen and one American I know have co-opted the day and made it an “unofficial” soccer holiday.

My friend Jimmie’s son was born seven years ago on Boxing Day, and ever since he has an open house for his soccer-loving friends and family. He wants his son’s birthday to always be filled with soccer. His house is just seven exits away on the Garden State Parkway (yes, the “Which exit?” New Jersey joke lives on) so my son and I watch a Premier League match as we eat an early morning English breakfast.

Phil, an Englishman, just started his Boxing Day party, but we’ll have to pass on it as one in our hometown gets top billing. Steve, a Scouser who supports Liverpool, has hosted a match and after-party for a number of years now.

The event starts as an eleven-a-side “international” between England and the U.S.A., but disintegrates into a twenty-a-side melee when the kids join in. It ends with a party at the local Elks Lodge. Last year, the Stars and Stripes posted a convincing 4-1 victory over Mother England on a clear, cold day. One player dressed as a Victorian-era Englishman with a retro Three Lions jersey, long white shorts, and a faux mustache. After the match we warm ourselves with meat pies and beer.

It’s a festive day of food and football that others should partake in. Soccer clubs could use it as a get-together after the fall season. Professional clubs might use the opportunity to stage an exhibition match, advertise the coming season (Major League Soccer just announced its home openers for 2013 this past week), or just host fans for a holiday party.

Whatever the motivation, December 26 could become a day that gets you off the couch and back onto the field. With soccer as its focus, it would be better than any of those other Hallmark Holidays.