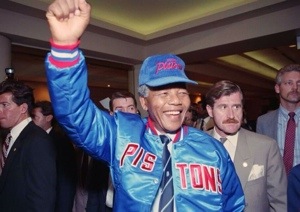

Sport is serious fun. Nelson Mandela, a keen amateur boxer in his youth, appreciated how the antiapartheid sport boycott assisted South Africa’s liberation struggle and, as a democratically elected president, he used the “politics of pleasure” to propel Rainbow Nationalism. Team sports like football reveal much about the experiences and mindsets of neighborhoods, cities, and nations. “The way we play the game, organize it and reward it reflects the kind of community we are,” is how Arthur Hopcraft put it in The Football Man (1968), one of the finest football books ever written.

Sport is serious fun. Nelson Mandela, a keen amateur boxer in his youth, appreciated how the antiapartheid sport boycott assisted South Africa’s liberation struggle and, as a democratically elected president, he used the “politics of pleasure” to propel Rainbow Nationalism. Team sports like football reveal much about the experiences and mindsets of neighborhoods, cities, and nations. “The way we play the game, organize it and reward it reflects the kind of community we are,” is how Arthur Hopcraft put it in The Football Man (1968), one of the finest football books ever written.

These issues strike at the heart of a new project I am embarking on with my Latin Americanist colleague Brenda Elsey, author of a splendid book on fútbol and politics in Chile. Brenda and I will be editing a special issue of Radical History Review on “Historicizing the Politics and Pleasure of Sport.” This marks the first time RHR, an academic journal known for “addressing issues of gender, race, sexuality, imperialism, and class, and stretching the boundaries of historical analysis to explore Western and non-Western histories” will turn its attention to sport. The issue is scheduled for publication in 2016.

Here’s the call for papers:

The global reach of football (soccer), basketball, cricket, and Olympic sports in the contemporary world can be traced back to European and U.S. imperial and commercial expansion. The agents of that imperialism—teachers, soldiers, traders, and colonial officials— believed sport to be an important part of their “civilizing mission.” Military interventions in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, often accompanied by “soft power” cultural programs and private business ventures, fueled the popularity of Western sports. Reform movements tied eugenics and racism to their dissemination. But local elites and subalterns were not simply duped; they enjoyed the games on their own terms. As more communities participated, sport came to represent and constitute broader processes of social change. In the stands, sports pages, and clubhouses, fans rendered sport a place to debate racial and gender hierarchies. In the late twentieth century, international sport became part of a new global capitalist network of sport institutions (e.g. FIFA, International Olympic Committee, International Cricket Council), private corporations, mass media, and migrant athletes and coaches. In this process, sport came to symbolize and intensify unequal social and economic relations.

Histories of sport reveal a paradox: sport generates empowerment and disempowerment; inclusion and exclusion; unity and division. Sports have provided spaces for pleasure, freedom, solidarity, and resistance, but they have also reproduced class privilege, patriarchy, and racism. The performance of masculinities, creation of ideal body types, and the ongoing marginalization of women in sport illustrate these tensions. Recent events in Brazil, where controversy over contemporary mega sporting events merged with massive demonstrations for a range of social justice issues, highlight the unusual capacity of sport both to crystallize inequalities and to trigger civic activism. Reports of labor abuses in Qatar and censorship and environmental damage in Russia cast a dark shadow on the human and material costs of hosting “mega” sports events.

The editors invite submissions from scholars working on any period and world region. We are especially interested in studies that build upon the rich historiography about the nature of agency, identity, and embodiment as a way to explore sport’s contradictory past and present.

Author: Peter Alegi

On December 5, Jonathan Wilson, journalist, author, and founding editor of The Blizzard, and the Football Scholars Forum convened for an online session devoted to independent fútbol writing in a digital age.

On December 5, Jonathan Wilson, journalist, author, and founding editor of The Blizzard, and the Football Scholars Forum convened for an online session devoted to independent fútbol writing in a digital age.

Wilson fielded a range of questions from an international audience from five continents. The 90-minute conversation blended English pragmatism and fútbol romantico, and indirectly grappled with Simon Kuper’s critique that “Football just isn’t what it’s cracked up to be,” and “anyone who peeks behind football’s curtain discovers there is no magic there.”

The Forum with Wilson pivoted around the notion that there is a growing English-speaking audience for longer-form writing about the game that goes beyond mixed-zone clichès, diatribes about managers, questionable refereeing decisions, and other narrow, shallow concerns of so much contemporary sport journalism. The challenges and opportunities of publishing in print and digital formats sparked conversation and debate, as did the evolving relationship between the futbology work of reporters and academics.

The audio recording of the session is available here.

For a Storify Twitter timeline click here, with special thanks to Liz Timbs (@tizlimbs).

Learn more about the Football Scholars Forum here.

Jonathan Wilson, journalist, author, and founding editor of The Blizzard, is the featured guest at the Football Scholars Forum on Thursday, December 5. Starting at 4pm Eastern (9pm GMT), the online football think tank will discuss the craft of independent fútbol writing in a digital age.

Jonathan Wilson, journalist, author, and founding editor of The Blizzard, is the featured guest at the Football Scholars Forum on Thursday, December 5. Starting at 4pm Eastern (9pm GMT), the online football think tank will discuss the craft of independent fútbol writing in a digital age.

Born in a pub after a Sunderland 4-0 demolition of Bolton in 2010, The Blizzard is a football quarterly that, Wilson says, is “neither magazine nor book, but somewhere in between.” It combines short- and long-form writing and is available in both analog and digital formats. The experience of independent English-language publications like The Blizzard and the recently defunct U.S.-based XI Quarterly, or Howler for that matter, suggests that journalists and scholars share many similar challenges and opportunities in publishing rigorously entertaining, meaningful football writing aimed at readers worldwide. [Click here to read my 2012 blog post on football at the intersection of academic research and popular journalism.]

Issue Nine of The Blizzard is being served up for Thursday’s session [download it here]. Its tasty menu includes: David Conn on the rise of Manchester, and Manchester City; Simon Kuper’s dissection of Barcelona tactics; Philippe Auclair interview with Michael Garcia, Fifa’s Ethics Committee chairman [sic!]; Gwendolyn Oxenham’s search for a pickup game in Teheran; and Igor Rabiner speaking with Lev Yashin’s widow.

To participate in the 90-minute session that takes place simultaneously at Michigan State University and online via Skype, please contact me asap (alegi.peter AT gmail.com) with your Skype name. Folks can also email or tweet me (@futbolprof) questions before the session.

Football and Independence in Zambia

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

LUSAKA—On a rainy Friday evening at the Pamodzi Hotel, Zambia Open University Professor Ackson Kanduza, president of the Southern African Historical Society, convened a forum based on my paper “Football and Independence in Zambia: A Political and Social History 1950s-1964.”

Part of my doctoral research on colonial and postcolonial Zambian football, the paper draws on archival, newspaper, and oral sources to argue that the changing culture of the African game influenced the anti-colonial nationalist struggle by fighting racial segregation and promoting African leaders to highly visible and prestigious administrative positions before independence.

In the early 1960s, colonial racism in then-Northern Rhodesia was still intense. Segregation kept Africans out of European-owned shops and forced black customers to shop through a window instead; Africans were not allowed to enter whites-only train carriages and buses; and jobs paying higher wages were reserved for whites.

But in 1961-62, black and liberal white businessmen founded the nonracial (racially mixed) National Football League. A black man, Tom Mtine, was named chairman of an otherwise white-dominated league executive. Two years prior to independence, the NFL permitted black players to be on the same teams as whites, and Africans were also allowed to represent the territory in international competitions. The emergence of black administrators like Tom Mtine and the game’s function as a “neutral” cultural form among people speaking 73 languages helped to assert black power as well as a sense of Zambian-ness that cannot be ignored in the history of Zambia.

An audience of both academics and members of the general public posed interesting questions and offered constructive comments. Most participants agreed with me that these sporting events signified an important step towards political freedom. Some noted that as Zambians celebrated their country’s 40th independence anniversary, my historical evidence about black leaders in football and the hosting of an international football tournament in 1964 to celebrate the nation’s birth would be highly appreciated by millions of Zambians. The discussion also grappled with the seemingly contradictory evidence that the British believed the game to be part of the “white man’s burden” while local people used it to fight colonial oppression.

“I did not know that our football has such a rich history,” said Pride Mwaanga; “I was wondering about the connection between football and independence, but now it makes sense!” Other participants asked why this rich history of Zambian football has not yet been explored. Echoing the conclusions of Marissa Moorman’s recent history of music and nationhood in the musseques (shantytowns) of colonial Luanda, Angola, audience members highlighted how, unlike anti-colonial political leaders, Zambian football administrators and players’ contributions to building the Zambian nation are not recognized in typical historical accounts.

Participants also stressed the need to publish biographies of past footballing greats such as “Ucar” Godfrey Chitalu, Dickson Makwaza, John “Ginger” Pensulo and many, many others. Professor Moses Musonda, Zambia Open University Deputy Vice Chancellor, pointed out that we need more scholars to research and write the history of football in Zambia, otherwise we are going to lose this valuable past.

Other interesting contributions came from Mrs. Kanduza and, again, from Prof. Musonda, who both gave testimonies of how they experienced leisure activities in welfare centers during the colonial era. These social centers played a critical role in the development of football. Prof. Musonda stated that Europeans enforced separate social institutions such as welfare halls to make sure that young Africans did not have the opportunity to challenge young Europeans in sport. Ironically, the same welfare centers and sporting facilities helped African men and women build their self-esteem and were later turned into avenues for political agitation.

Prof. Kanduza concluded the event by pointing out that a goal of the Zambia Open University is to organize forums that give opportunities to listen to unheard local voices. He highlighted how the research and discussion of “Football and Independence in Zambia” captures voices and conveys the historical experiences of African people through the prism of sport. The evening ended with a promise to organize more of these lively and insightful sessions in the near future.

—

*Hikabwa Chipande is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at Michigan State University. He is currently in Lusaka researching the social, cultural and political history of football in colonial and postcolonial Zambia. Follow him on Twitter at @hikabwachipande

Punk Football for the Working Class

We play therefore we are.

That, in essence, is the sentiment that motivated a group of disaffected Red Devils’ fans opposed to Malcolm Glazer’s $1.5 billion takeover in 2003 of Manchester United to quit Old Trafford and form a new club: FC United of Manchester.

Punk Football, a terrific and profoundly humanistic new documentary film, chronicles FC United’s dramatic 2012-13 campaign which brought them to the brink of promotion to the North Conference League—five levels below the glitz and glamor of the English Premier League.

We are introduced to FC United supporters, officials, players, and coaches who explain what it means to be a community football club owned and democratically run by 2825 co-owners, each holding one voting share. FC United’s manifesto makes it clear this is football by the people, for the people. Football for the working class. “FC United seeks to change the way that football is owned and run, putting supporters at the heart of everything,” states the club’s website. “It aims to show, by example, how this can work in practice by creating a sustainable, successful, fan-owned, democratic football club that creates real and lasting benefits to its members and local communities.”

Around the time of the film’s release, construction began on FC United’s new 5,000-capacity stadium. After wandering for years playing home matches at rented grounds, most recently at Gigg Lane in Bury, members raised more than £2m through a share scheme, and secured additional funding from Sport England, the Football Foundation, the City of Manchester, and Manchester College. (Click here for a recent news story about the stadium.)

The extraordinary story of FC United putting people and poetry before profits is beautifully told in this brilliant documentary. Don’t miss it!

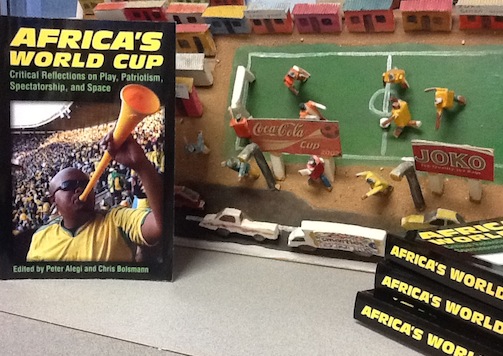

The Football Scholars Forum, an online fútbol think tank I co-founded at Michigan State University, recently launched its 2013-14 season. On October 24, FSF held a lively discussion of Africa’s World Cup: Critical Reflections on Play, Patriotism, Spectatorship, and Space, a newly published collection I edited with Dr. Chris Bolsmann, a South African sociologist based in the UK.

The 90-minute event opened with a consideration of the book’s attempt at blending scholarly and journalistic approaches to exploring the game and its broader implications. The editors and several chapter authors in attendance talked about the process of writing and editing, as well as their experience working with an academic press on a topic with potentially broad appeal.

The book, much of it written in the first person as a loving critique of the 2010 tournament, demonstrates how the FIFA World Cup story is entangled in a web of national and international politics, sporting culture, and global capitalism. Many interventions linked South Africa 2010 to Brazil 2014, particularly through the public financing of expensive and unsustainable new World Cup stadiums in countries with dysfunctional schools and hospitals and high rates of poverty and inequality. The online conversation also featured Luis Suarez’s handball against Ghana and the contradictory legacies of this “African” World Cup.

Participants logged in from half a dozen countries in North America, South America, Africa, and Europe. In attendance: Andrew Guest, Chris Bolsmann

, Christoph Wagner

, David Patrick Lane,

David Roberts,

Derek Catsam,

Jacqueline Mubanga,

Raj Raman,

Orli Bass

, Rwany Sibaja,

Laurent Dubois

, Achille Mbembe

, Jordan Pearson, Sean Jacobs, and Alex Galarza (all via Skype); and Liz Timbs,

Dave Glovsky,

Alejandro Gonzalez, and

Peter Alegi (in East Lansing).

For a Storify Twitter timeline of the event click here.

The audio recording of the discussion is freely available here.

The next Football Scholars Forum event on November 14 will focus on Soccer in the Middle East, a special issue of the journal Soccer and Society (2012), edited by Alon Raab and Issam Khalidi.

Boca Júniors’ “Fraud of the Century”

On October 3-4, Alex Galarza spoke at the Rethinking Sports in the Americas conference at Emory University about the history of Club Atlético Boca Júniors’ Ciudad Deportiva (“sports city”), a gargantuan urban project hailed in the 1960s as a harbinger of national progress and modernization that later became known as the “fraud of the century.” Galarza is a doctoral student in history at Michigan State University and co-founder of the Football Scholars Forum. This paper is part of ongoing doctoral research funded by the Fulbright Program and a FIFA Havelange Scholarship.

The scholarly gathering in Atlanta provided ten early career scholars and graduate students with a chance to present new research papers and receive feedback from peers and senior scholars. Participants read and commented on pre-circulated papers, which made for lively and engaging discussions. Chris Brown, an Emory History PhD student studying sport in the Brazilian Amazon, organized the conference with support from Dr. Jeff Lesser of the Emory History Department and Dr. Raanan Rein, Vice President of Tel Aviv University. Several Football Scholars Forum members shared their work and ideas, including keynote speaker, Brenda Elsey, as well as Rwany Sibaja and Ingrid Bolívar.

The video of Alex Galarza’s presentation on the Ciudad Deportiva reveals the intertwining of sport, politics, and society in postwar Buenos Aires. The Ciudad was profoundly shaped by the idea that popular consumption of fútbol and leisure were integral components of citizenship and national progress. This helps explain why Argentina’s national government and Buenos Aires’ municipal authorities subsidized the project and integrated it into the city’s master plan. The general public, not just Boca supporters, invested an impressive amount of money and faith into the undertaking. While the initial success of the Ciudad speaks to the changing ways in which porteños viewed modernity and consumed leisure, the project’s monumental failure in the long run sheds new light on the nature of political and economic change in Argentina after Perón.