In this video, Alex Galarza and I discuss digital fútbol scholarship at Michigan State University. The conversation ranges from Galarza’s doctoral dissertation entitled “Between Civic Association and Mass Consumption: The Soccer Clubs of Buenos Aires,” to the Football Scholars Forum, the online football think tank.

For more information about Galarza’s research click here.

Author: Peter Alegi

Nigeria’s Triumph, Africa’s Tournament

Photos courtesy of Chris Bolsmann

By Chris Bolsmann (@ChrisBolsmann) and Marc Fletcher (@MarcFletcher1)

February 11, 2013 (23rd anniversary of Mandela’s release from prison.)

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA

Chris Bolsmann (CB): In February 1996, I celebrated with 100,000 other delirious South Africans packed into Soccer City after we beat Tunisia in the African Nations Cup final. It was a special victory and an important moment in South African sports history. It was more special that the 1995 rugby World Cup win because the soccer crown was won by a genuinely racially integrated team playing the game obsessively followed by most South Africans. 1996 has remained a very powerful memory for me over the last 17 years. However, there has always been one lingering doubt in the back of my mind: Nigeria, the reigning African champions at the time, did not participate.

The Nigerian junta’s sham trial and execution in November 1995 of author and environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa drew a sharp rebuke from then-South African President Nelson Mandela. Relations between the two countries quickly deteriorated and led to the reigning champions’ withdrawal from the 1996 tournament in South Africa. These events intensified the heated rivalry between South Africa and Nigeria. For Sunday’s final I had planned to support Burkina Faso. The Burkinabé had reached their first-ever Nations Cup final by playing exciting and entertaining football; they were also the under-dogs.

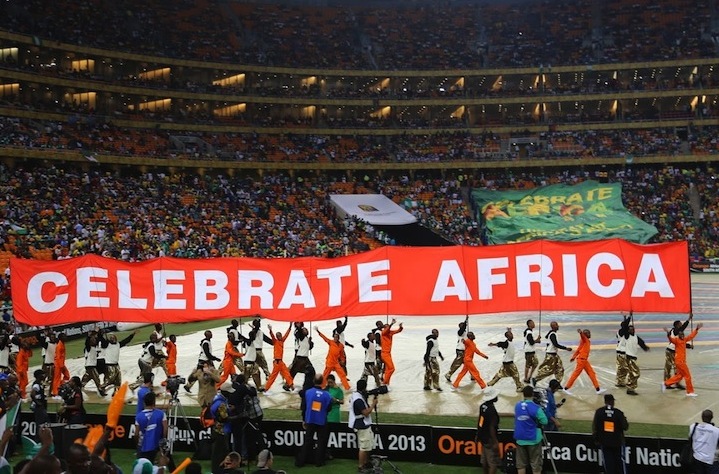

Marc Fletcher (MF): I arrived at Soccer City’s National Stadium almost four hours before Sunday’s kickoff and was pleased to see that the Nations Cup party atmosphere had finally hit Johannesburg. Considering the large Nigerian population in the city, it was unsurprising that the vast majority of the fans streaming in were Super Eagles supporters. More surprising was the significant number of South Africans choosing to support Nigeria. After all, “Nigerians” here are perceived as illegal immigrants and dangerous criminals. Tensions between African immigrant communities and South Africans have sometimes spilled over into xenophobic attacks, as in the deadly riots of 2008. But the Nations Cup final appeared to turn this association upside down; being Nigerian, or identifying with Nigeria, had become a positive thing, if only temporarily.

Walking towards the spectacular stadium, it was also apparent how this experience differed from the World Cup I attended almost three years before. Back then, football fans had been promised an “African” World Cup (whatever that entailed). South Africans and tourists alike had been repeatedly told that “It’s Africa’s Turn” and that South Africa would show the world the positives Africa had to offer. Instead, a bland, commercialised FIFA-controlled environment reduced the local flavour of the tournament to the controversy surrounding vuvuzelas. As one of my local research informants summarised, “this could be anywhere!”

Walking towards the spectacular stadium, it was also apparent how this experience differed from the World Cup I attended almost three years before. Back then, football fans had been promised an “African” World Cup (whatever that entailed). South Africans and tourists alike had been repeatedly told that “It’s Africa’s Turn” and that South Africa would show the world the positives Africa had to offer. Instead, a bland, commercialised FIFA-controlled environment reduced the local flavour of the tournament to the controversy surrounding vuvuzelas. As one of my local research informants summarised, “this could be anywhere!”

But 2013 was different. Cheaper tickets must have been a factor, allowing those who could not attend World Cup matches to engage, to experience and to celebrate. The bland hot dogs of the World Cup had been replaced with the pap and steak and boerwors rolls, staple foods at domestic matches. The relentless drumming from the small group of Burkinabé in the seats near me infused the tournament with the beat that had been lacking nearly three years ago. People of different racial, ethnic, class, and gender backgrounds socialised with one another–a dream for Rainbow Nation proponents–while the vast panoply of different African football shirts and flags reinforced a wider belonging to “Africa.” Security checks on spectators were inconsistent at best. A feeble, half-hearted pat down from a steward would do little to detect things such as flares, which constantly happens at local games (my favourite is still seeing someone pull out a full bottle of whiskey from his sock!). The pitch resembled a beach with players kicking up clouds of sand constantly. When Nigeria went ahead through Sunday Mba’s brilliant goal three-quarters of the stadium erupted in celebration. A far cry from the World Cup.

CB: Our tickets for the final were purchased months in advance, but as we tried to get to our seats it was clear that Nigerian fans occupied this part of the stadium. After stern words and persistence, we finally sat in our seats. It took stadium security and the South African police a good thirty minutes of the first half to move Nigerian fans seated on the stairs next to us to proper seats. I chatted to Sunday, a Nigerian national who told me he currently lives in Germiston on the East Rand (part of greater Johannesburg). Directly behind us was a group of eight or so trumpeters and a couple of drummers who played throughout the match. It was hard not to sway and dance to the fantastic music. By the time Nigeria took the lead my fickle allegiance was swaying towards the Super Eagles. When the final whistle blew I was happy Nigeria had won their third African title and had done so on South African soil. I look forward to Nigeria representing Africa at the Confederations Cup in Brazil later this year. But even more exciting is the prospect of South Africa regaining the lofty heights of 1996 and a show down with Nigeria. Despite Bafana’s quarterfinal exit, I carry on believing.

MF: I’ve fallen into the trap of comparing a westernised, modern, slick, commercialised World Cup with the chaotic yet dynamic African tournament. I’m not sure how to extricate myself from this other than to continue digging my hole with my romanticism of the final. It was a vibrant celebration of African football. Yet, as I drove to work this morning, the newspaper headlines attached to most Jo’burg streetlights were not about the final but Manchester United extending their lead at the top of the English Premier League. Is the 2013 Africa Cup of Nations already being forgotten?

MF: I’ve fallen into the trap of comparing a westernised, modern, slick, commercialised World Cup with the chaotic yet dynamic African tournament. I’m not sure how to extricate myself from this other than to continue digging my hole with my romanticism of the final. It was a vibrant celebration of African football. Yet, as I drove to work this morning, the newspaper headlines attached to most Jo’burg streetlights were not about the final but Manchester United extending their lead at the top of the English Premier League. Is the 2013 Africa Cup of Nations already being forgotten?

Guest Post by Marc Fletcher* (cross-posted with permission of Africa is a Country and the author.)

One of the key sights of this year’s Africa Cup of Nations has been emptiness. Aside from the opener between South Africa and Cape Verde, the television cameras have picked up images of large swathes of empty seats. Whether it was Burkina Faso’s last gasp equalizer against Nigeria in Nelspruit or Tunisia’s equally late winner versus Algeria in Rustenburg, the empty seats appeared to outnumber the fans that had made the trip. Coverage from previous editions of the tournament in Ghana, Angola and Equatorial Guinea picked up similar images. This is clearly not a South African-only problem.

I had earlier hoped that the more reasonable pricing structure for this tournament as opposed to the 2010 World Cup would have made the games more accessible to majority of poorer, working class football fans; those who make up the vast majority of the support base of South Africa’s domestic clubs. The empty seats suggest that it’s reaching few people in general.

So what are the issues behind this?

Firstly, there aren’t many players in this tournament that can be described as superstars. In the World Cup, there was Messi, Ronaldo and the entire Spanish squad. This time around, there’s Didier Drogba, whose career is winding down in China but few others. Yes, there are players such as Yaya Touré and Asamoah Gyan but they simply do not have the same star status. Why spend hard-earned money to watch two teams that you have little or no interest in?

Secondly, the 5 pm kick off times are hardly conducive to getting bums on seats. As I write this, I have one eye on the Bafana v Angola match. While attendance seems to be significantly greater than in most of the other matches, there are still many empty seats. Traffic at this time in the major cities can be nightmarish and some fans will be unwilling to put themselves through the gridlock and confusion. To make sure that you get to the stadium in plenty of time means taking the afternoon off work.

A big contributory factor is that that there are few, if any African countries that have a large fan base with a large enough disposable income to fly out to the southern tip of the continent for the tournament. Unlike the vast hoards of traveling football tourists at the Euros or at the World Cup, the support of visiting teams is usually restricted to a small rump of die-hard regular fans who are sometimes subsided by the state or political parties. While the commitment on the part of these fans is impressive, this is not going to fill these former World Cup venue. This is a problem that is not going to go away anytime soon.

But the thing that strikes me most as I write from Johannesburg is the absence of evidence that the tournament is taking place. In 2010, there were numerous posters around the city, large fan parks with big screens and people blowing vuvuzelas on street corners. Thousands crammed onto the streets in the north of the city when Bafana went on an open-top bus tour while a giant photo of Cristiano Ronaldo was emblazoned on Nelson Mandela Bridge. This time, it is severely underwhelming. There is no party atmosphere, no fan parks, little hype on local television or radio. Bafana shirts are far less apparent on the street in contrast to 2010. It’s not totally absent though. Staff at my local Spar were wearing their Bafana shirts today, while bar staff on Soweto’s tourist strip on Vilakazi Street were doing the same.

Still, it’s as if the tournament has passed Jo’burg by and I wouldn’t be surprised if it passes most of South Africa by with little more than a passing awareness that Africa’s biggest football tournament is in their country. The slogan of the tournament is “The beat at Africa’s feet,” but this beat is strangely subdued.

Maybe people realize that they have more important things to do than watch football?

N.B. During the South Africa vs Angola match, Moses Mabhida stadium in Durban seemed to be fuller in the second half. The commentator on Supersport (the South African satellite channel that dominates football broadcasting on the continent) has suggested that there is an excessive number of security cordons, which has delayed many fans from getting into the ground until the latter part of the first half.

* Marc Fletcher (MarcFletcher1), a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Johannesburg, blogs at One Man and His Football: Tales of the Global Game.

Alex Galarza, a PhD student in history at Michigan State University and co-founder of the Football Scholars Forum, has been awarded the João Havelange Research Scholarship. This prestigious award is administered jointly by FIFA and CIES (Centre International d’Etude du Sport), an independent research center created in 1995 by the governing body in collaboration with the University of Neuchâtel, and the City and State of Neuchatel, Switzerland.

Alex Galarza, a PhD student in history at Michigan State University and co-founder of the Football Scholars Forum, has been awarded the João Havelange Research Scholarship. This prestigious award is administered jointly by FIFA and CIES (Centre International d’Etude du Sport), an independent research center created in 1995 by the governing body in collaboration with the University of Neuchâtel, and the City and State of Neuchatel, Switzerland.

Galarza’s project is titled “Between Civic Association and Mass Consumption: The Soccer Clubs of Buenos Aires.” It explores how clubs developed as both centers of mass spectacle and sites of everyday urban sociability. Club members and officials used political connections to secure city space and public subsidies for stadiums and the overall success of their professional teams. While clubs became centers of patronage and spectacle, they were also non-profit civic associations central to social and cultural activities in the city. Clubs provided educational facilities, libraries, leisure space, and political forums for their members.

Galarza’s research examines the tensions within football clubs during the mid-twentieth century, an era when Argentine society entered a period of deep economic and political changes following the ouster of Juan Domingo Perón in 1955. Perón’s project aimed at developing a new kind of citizen and civic culture in which the popular classes would have a greater political voice and heightened access to new forms of mass consumption. Mass political participation and consumption remained critical and unresolved tensions during the democratic and military governments that followed. One powerful example of how soccer clubs gave shape and meaning to civic engagement, popular spectacle, and mass consumption is Boca Juniors’ Ciudad Deportiva (in photo above). This failed project was a mix between a stadium complex and amusement park, built over seven artificial islands on sixty hectares of land filled in the Rio de la Plata.

Click here to read a digital version of Galarza’s preliminary work on the fascinating history of the Ciudad Deportiva.

Check back with us for an interview with Galarza in the coming days.

These are interesting times for politics and football in South Africa. The African National Congress is meeting this week in Bloemfontein/Mangaung to select the ruling party’s new leaders while 94-year-old Nelson Mandela is still hospitalized recovering from surgery and a lung infection. Domestic football has been rocked by a FIFA match fixing report alleging that a transnational match-fixing syndicate based in Singapore, assisted by South African Football Association (SAFA) officials, fixed Bafana Bafana’s friendlies against Thailand, Bulgaria, Colombia and Guatemala in the build up to the 2010 World Cup. Five SAFA men, including its president, Kirsten Nematandani (in photo above), have been suspended pending “further examination” of possible “criminal intent in collusion” with a front organization set up by the convicted match fixer Wilson Raj Perumal.

These are interesting times for politics and football in South Africa. The African National Congress is meeting this week in Bloemfontein/Mangaung to select the ruling party’s new leaders while 94-year-old Nelson Mandela is still hospitalized recovering from surgery and a lung infection. Domestic football has been rocked by a FIFA match fixing report alleging that a transnational match-fixing syndicate based in Singapore, assisted by South African Football Association (SAFA) officials, fixed Bafana Bafana’s friendlies against Thailand, Bulgaria, Colombia and Guatemala in the build up to the 2010 World Cup. Five SAFA men, including its president, Kirsten Nematandani (in photo above), have been suspended pending “further examination” of possible “criminal intent in collusion” with a front organization set up by the convicted match fixer Wilson Raj Perumal.

Consumed by the details of this latest sporting malfeasance as well as the tensions in ANC politics at a particularly difficult moment for South Africa, I was stunned to belatedly learn of the death of Sedick Isaacs at the age of 72. I had the extraordinary privilege to meet him in 2010 while a Fulbright Scholar at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN). I was humbled and honored to share the stage with Isaacs in a symposium on football history held on the UKZN Westville campus and sponsored by the German cultural exchange program, DAAD.

Isaacs spoke matter-of-factly about the cruelty and hardships endured during his 13 years on Robben Island. What had earned him a place in apartheid’s most notorious prison had been his role as saboteur in the armed struggle. Standing before us wearing a blue sweater in the humidity of sub-tropical Durban, Isaacs pointed out that his years on Robben Island had left him always feeling cold regardless of the temperature. A point he reiterated in Cape Town two weeks later when he spoke at my book launch for African Soccerscapes. (That’s us in the photo below.)

By studying and playing on Robben Island, Isaacs told us, prisoners formed and maintained communities of survival and resistance. He earned a university degree while behind bars and also helped to build and administer the prisoners’ Makana Football Association. (The story is admirably told by Chuck Korr and Marvin Close in More Than Just a Game: Football v Apartheid.) When the prisoners finally secured the warden’s approval for their league after three years of struggle, Isaacs ended up handling much of the day-to-day operations of the Makana FA.

Dr. Isaacs explained that the weekly cycle of matches proved crucial in fighting “eventless time” — a debilitating condition for prisoners serving lengthy sentences. The cycle worked something like this: teams started the week by analyzing the previous match and then by midweek there was growing anticipation for upcoming matches. Conversations, banter, and meetings stoked the hype and created heroes and personalities. By the weekend, excitement surrounding the matches reached fever pitch. Football’s importance, Isaacs said, was enhanced by its force as a provider of human emotions in an emotionally neutral context.

Dr. Isaacs explained that the weekly cycle of matches proved crucial in fighting “eventless time” — a debilitating condition for prisoners serving lengthy sentences. The cycle worked something like this: teams started the week by analyzing the previous match and then by midweek there was growing anticipation for upcoming matches. Conversations, banter, and meetings stoked the hype and created heroes and personalities. By the weekend, excitement surrounding the matches reached fever pitch. Football’s importance, Isaacs said, was enhanced by its force as a provider of human emotions in an emotionally neutral context.

Isaacs pointed out that the only positive effects of long prison sentences is that they can strengthen prisoners’ organizational skills and improve their understanding of human nature. The activities of the Makana FA reinforced this outcome. Intriguingly, both candidates for the ANC presidency in 2012, South African President Jacob Zuma and his challenger Kgalema Motlanthe, played football on Robben Island. “If it had not been for the beautiful game and these community building devices,” Isaacs concluded, “we could have become psychological and physical wrecks incapable of integration into a multicultural world, let alone be able to contribute positively to it.” May you rest in peace Sedick Isaacs. An exemplary South African who can teach folks in Mangaung and at SAFA a few lessons about doing the right thing in politics and football.

The 90th Minute Trailer from Jun Stinson on Vimeo.

The Football Scholars Forum is holding its final session of the 2012 season on Wednesday, December 5, at 3:30pm EST, on Jun Stinson’s short film, The 90th Minute. The 20-minute documentary follows three members of FC Gold Pride, the 2010 Women’s Professional Soccer champions. The film sheds light on what it’s like to be a female pro player in the U.S. — a dream that has become more elusive after the demise of the WPS.

Why do Hope Solo, Alex Morgan, Megan Rapinoe, Abby Wambach and others struggle to play professionally in their country? Why have two pro women’s soccer leagues failed since the heady days of Mia Hamm, Brandi Chastain and the 1999 Women’s World Cup? What needs to happen for a new women’s league in the U.S. to be sustainable? How does the situation in the U.S. compare with international trends?

Jun Stinson recorded an interview with me ahead of the session in which I also asked a few questions on behalf of FSF members. To listen click here. Gwen Oxenham, former Duke and Santos player and one of the producers of the film Pelada will participate in what promises to be a terrific season finale!

For more information about this event please contact Alex Galarza: galarza1 [at] msu [dot] edu.

Update: On November 21, “U.S. Soccer president Sunil Gulati announced the launch of a women’s professional league which will start play in March.” Details here.

Théophile Abega, the heart and soul of Cameroon’s superb national team of the 1980s, has died at the age of 58. Thoughtful, elegant, and tough, Abega had an illustrious club career with Canon Yaoundé. He was a dominant force in the team that twice won the African Champions Cup (1978, 1980), the African Cup Winners’ Cup (1976, 1979), and three domestic league titles. Abega’s only World Cup participation was in 1982 in Spain, where Cameroon drew all three group stage matches against Peru, Poland, and Italy.

I remember watching him on TV against my beloved Azzurri in an extraordinarily tense contest with qualification to the next round on the line. Abega’s composure, strength, and technique were striking. As a result of the 1-1 draw, Cameroon was eliminated on goal difference (number of goals scored in fact) but nevertheless enhanced the image of African football on the global stage. Two years later, as the video above demonstrates, Abega was at his footballing peak as Cameroon defeated Nigeria 3-1 in the 1984 African Nations Cup final. The Indomitable Lions returned to international glory at the 1990 World Cup in Italy (Roger Milla!), but by that time Abega had closed out his career with Toulouse in France and no longer commanded Cameroon’s midfield with his consummate professionalism and style.

May his soul rest in peace.