Boosted by a home crowd of 20,000 fans, including President Teodoro Obiang Mbasogo, Equatorial Guinea crushed South Africa 4-0 in the final of the 8th African Women’s Championship in Malabo on Sunday.

Boosted by a home crowd of 20,000 fans, including President Teodoro Obiang Mbasogo, Equatorial Guinea crushed South Africa 4-0 in the final of the 8th African Women’s Championship in Malabo on Sunday.

Banyana Banyana — as the team is affectionately known — held out until the 43rd minute when the home team took the lead through Chinasa’s header from a corner kick. The goal seemed to take the wind out of Banyana’s sails. After the break the qualitative difference between the two sides became evident. Midway through the second half Banyana lost their concentration, giving up three goals in six minutes to the Nzalang Nacional (Nation’s light): Costa (66′), Anonman (70′) and Tiga (72′).

“Falling at the final hurdle is a major disappointment to all involved with Banyana Banyana,” said head coach Joseph Mkhonza at the post-match press conference. In a year that saw South Africa’s women’s team reach two major milestones, competing in the Olympics for the first time and finally beating powerhouse Nigeria, Mkhonza looked ahead and said that “Banyana Banyana should be able to qualify for international tournaments, such as the World Cup and the Olympics, in the future.”

It is always tough to play a final against the host nation, but the big game in hostile territory did appear to get the best of the South Africans. The night before the match, for example, Banyana captain Amanda Dlamini (@Amanda_Dlamini9) shared her state of mind on Twitter. “I don’t know how I’m going to sleep tonight. If I’m going to sleep at all,” she wrote. Then a few hours before the match, defender Janine Van Wyk (@Janinevanwyk5), whose marvelous goal beat Nigeria in Wednesday’s semifinal, tweeted: “Very IMPORTANT game today. I’m so nervous its [sic] insane but I know we will do well.” Perhaps adding to the pressure of the moment, the office of the Presidency (@PresidencyZA) followed by tweeting its support: “President Zuma wishes Banyana well.”

It is always tough to play a final against the host nation, but the big game in hostile territory did appear to get the best of the South Africans. The night before the match, for example, Banyana captain Amanda Dlamini (@Amanda_Dlamini9) shared her state of mind on Twitter. “I don’t know how I’m going to sleep tonight. If I’m going to sleep at all,” she wrote. Then a few hours before the match, defender Janine Van Wyk (@Janinevanwyk5), whose marvelous goal beat Nigeria in Wednesday’s semifinal, tweeted: “Very IMPORTANT game today. I’m so nervous its [sic] insane but I know we will do well.” Perhaps adding to the pressure of the moment, the office of the Presidency (@PresidencyZA) followed by tweeting its support: “President Zuma wishes Banyana well.”

That Banyana could not field three overseas players partly explains Sunday’s result. Midfielder Kylie Ann Louw and reserve goalkeeper Roxanne Barker stayed in the United States due to study commitments, while midfielder Nompumelelo Nyandeni remained with her club in Russia. “Losing a player of Nyandeni’s talent and experience will always be a setback to any team,” said Mkhonza. Another factor to consider has to do with oil-rich Equatorial Guinea’s “willingness to hand out passports to players who agree to play for them without any period of residency,” as Ian Malcolm of goal.com put it. “Almost the entire squad selected for the African Women’s Championship were born outside Equatorial Guinea, most in Brazil, but also in other African states.” While not illegal according to FIFA rules, the ethics of this all-star team formation are questionable.

The buzz about Banyana from South Africans on social media was overwhelmingly positive. “You did South Africa proud, the whole team deserves a heroes welcome. You passed all expectation and showed your greatness,” @RhandzuOptimus wrote in a tweet that captured the general tenor of South Africans’ reactions. The government chimed in too. Sports Minister Fikile Mbalula said that “Although they did not win the (African) Championships, Banyana Banyana have proven that they are an ever improving team that has shown progress over the last year.”

Now that the tournament is over what will happen to the “Banyana Bandwagon”? Practitioners and fans know that women’s football in South Africa needs much more investment and support. Even at the elite level there is no season-long national league. And as Thabo Dladla, founding director of Izichwe Youth Football in Pietermaritzburg, explains in a comment to my previous Banyana post: “There are no competitions for girls junior teams. Our girls only start playing football at the university level. These issues have nothing to do with money. SAFA should play the role in terms of promoting the game.” The road ahead is long and tortuous. We’ll be following developments closely.

Suggested Reading

Prishani Naidoo and Zanele Muholi, “Women’s bodies and the world of football in South Africa,” in Ashwin Desai, ed., Race to Transform: Sport in Post-Apartheid South Africa (HSRC Press, 2010).

Cynthia Fabrizio Pelak, “Women and gender in South African soccer: a brief history,” Soccer and Society 11, 1/2 (2010); 63-78.

Martha Saavedra, “Football Feminine—Development of the African Game: Senegal, Nigeria, and South Africa,” Soccer and Society 4, 2/3 (2003): 225-253.

Author: Peter Alegi

Banyana Bandwagon

South Africa’s women’s national team recorded its most important victory ever on November 7 by defeating Nigeria 1-0 in the semifinal of the 8th African Women’s Football Championship in Bata, Equatorial Guinea. Defender Janine Van Wyk long-range blast gave Banyana Banyana (The Girls) their first-ever win against the six-time champion Super Falcons. South Africa will face Equatorial Guinea in the final on Sunday, November 11, a team that beat them 1-0 in the first group stage match.

South Africa’s women’s national team recorded its most important victory ever on November 7 by defeating Nigeria 1-0 in the semifinal of the 8th African Women’s Football Championship in Bata, Equatorial Guinea. Defender Janine Van Wyk long-range blast gave Banyana Banyana (The Girls) their first-ever win against the six-time champion Super Falcons. South Africa will face Equatorial Guinea in the final on Sunday, November 11, a team that beat them 1-0 in the first group stage match.

“I have been in the Banyana Banyana side since 2004 and we have tried for so long to beat the Nigerians but luck has never been on our side, but now we have proved that we can compete and beat of the best on the continent,” said Van Wyk. “At the CAF African Championship held in South Africa in 2010 I scored with a free kick from 35 metres out against Nigeria, and my teammates always remind me that I normally reserve my best for matches against Nigeria,” she laughed.

With the men’s team — Bafana Bafana — struggling, it is perhaps not surprising that South African fans and the football establishment are leaping onto the Banyana bandwagon. Following the win against Nigeria, SAFA President Kirsten Nematandani announced he would be flying out to attend the final. “The victory should open doors for the growth of women’s soccer,” he said. “Well done to the girls for making the country proud.”

With the men’s team — Bafana Bafana — struggling, it is perhaps not surprising that South African fans and the football establishment are leaping onto the Banyana bandwagon. Following the win against Nigeria, SAFA President Kirsten Nematandani announced he would be flying out to attend the final. “The victory should open doors for the growth of women’s soccer,” he said. “Well done to the girls for making the country proud.”

“We are in a very positive frame of mind going into the final game against the hosts,” said Joseph Mkhonza, the Banyana head coach. “But we are still focused on attaining our mission of taking gold in this tournament. We came here with a mission and that mission is still on track,” he said. “We have some homework to do before Sunday’s final, knowing we will play in front of a large red-clad crowd in what is certain to be a packed Malabo stadium, but we will be ready for the challenge.”

Fútbologia: Talking Football in Bologna

I caught the football virus early on in life. Growing up in Rome, some of my earliest memories of pure freedom and unadulterated joy had to do with playing football with my brothers, friends, and school mates in courtyards, playgrounds, streets and on the dirt and gravel pitches of Villa Ada and Villa Borghese. Eventually, I made it into the CONI Acqua Acetosa football academy, which in the 1970s was a bountiful feeder program for youth development programs across the city, including Roma and Lazio.

This was around the time of the Iranian Revolution and the U.S. Embassy hostage crisis (go see Argo if you haven’t yet). When our creative writing teacher demanded an essay on a global topic, I cheekily produced a (handwritten) lengthy fiction piece about an Iran vs. U.S. “peace match” in Tehran. I coreographed it tightly. President Carter and Ayatollah Khomeini sat next to each other in the VIP seats (!) and at the end of the match the unifying power of sport resolved the diplomatic crisis. Nothing like a young boy’s idealism and imagination!

These childhood memories were suddenly stirred up when I learned about “Fútbologia 2012” — a day-long gathering to be held in Bologna on Saturday, November 3. John Foot, lecturer in Italian history at the University of London and author of Calcio: A History of Italian Football will give a keynote address (follow him on Twitter @footymac) based on his book and the evolution of football writing in Italy and abroad.

I liked the emotional, unpretentious prose of the event’s official description, as well as its philosophical thrust. “We sniff football from when we are kids. The smell of mold in the dressing room, shoe polish, sweaty uniforms,” write the Fútbologia organizers. “Entire lineups memorized. We watch football since forever. We recognize stadiums from around the world. And yet the level of discourse on football in Italy is very modest. And its global business system is in deep shit. We’ve been having less fun for quite some time. But now we have a plan. A conversation about football from a historical perspective, comparative and contemporary. About power and popular culture. Social sciences and physical sciences, art and literature. High pressing and Tahrir Square.”

Now that’s what I call a Saturday well spent. Buon divertimento!

For more information visit the futbologia.org blog.

“Neither magazine nor book, but somewhere in between,” is how journalist and author Jonathan Wilson describes the genre of long-form football writing currently gaining popularity in the United States and Britain. I call this genre the bookzine, a hybrid form that lies at the intersection of academia and popular journalism.

“Neither magazine nor book, but somewhere in between,” is how journalist and author Jonathan Wilson describes the genre of long-form football writing currently gaining popularity in the United States and Britain. I call this genre the bookzine, a hybrid form that lies at the intersection of academia and popular journalism.

In an insightful article at Forbes.com, Zach Slaton notes how in September 2012 “three English-language print publications – XI Quarterly, The Blizzard, and Howler – either debuted or had their latest issue released all within a month of each other.” Each of the three magazines has a distinct style, edge, form, and funding model. Published in both print and digital editions, XI Quarterly and The Blizzard are more narrative and non-commercial than Howler, which emphasizes visual graphics and has a deal with Nike. “We’re embarking on a golden age for such writing,” Slaton writes, one “that may just be sustainable given the niches each one fills.”

The main triggers powering this new trend, according to Slaton, are “the globalization of the game and the tearing down of historical publishing structures.” He’s right, of course, as satellite and cable television, Web publishing, video and audio streaming online, Facebook, and Twitter expanded access for soccer junkies almost everywhere.

Having spent almost twenty years as a sort of football academic, I wonder why this supposed “golden era” is happening right now. Are there some deeper, longer-term factors fueling this sudden explosion of bookzines?

On Friday, Howard Riddle, Senior District Judge in the Westminster Magistrates’ Court, found Chelsea captain John Terry not guilty of racially abusing Queen’s Park Rangers Anton Ferdinand. Here are eight things I learned by reading Judge Riddle’s decision:

1. “There is no doubt that John Terry uttered the words ‘fucking black cunt’ at Anton Ferdinand” (p.13).

2. TV footage unequivocally demonstrates that “Terry directed the words ‘black cunt’ in the direction of Anton Ferdinand” (p.3).

3. In a statement to the English FA Terry 5 days after the incident, remembered saying to Ferdinand “I think it was something along the lines of, ‘You black cunt, you’re a fucking knobhead'” (p.10).

4. Lip reading experts are amazing people who do important work, but this doesn’t mean much in the big picture.

5. Terry said what he said in the heat of the game and was angry, physically and mentally tired (pp.13-14). Seriously.

6. Give money to a charity in Africa: it’s a great alibi (as Elliot Ross explains here).

7. That nobody on the pitch claims to have heard Terry calling Ferdinand a “fucking black cunt” at the time and that “there are limitations to lip reading” [p. 14]) was used to obfuscate the undisputed factual evidence of the video footage.

8. The “not guilty” verdict reflects tortuously twisted logic. The decision seems to hinge on the possibility that Terry hurled the insult at Ferdinand only after the latter had “accused Mr Terry on the pitch of calling him a black cunt” (p. 14). “It is therefore possible,” Judge Riddle concludes, “that what he said was not intended as an insult, but rather as a challenge to what he believed had been said to him” (p. 15). So let me see if I understand this legal reasoning correctly: it is not racially abusive speech to call a black person a “fucking black cunt” if it’s in response to an accusation of calling you a fucking black cunt. Huh?

As @NutmegRadio eloquently tweeted: “The John Terry verdict now stands as a how-to-guide for how to escape a racially aggravated public order offense in the UK.”

Spain: The Greatest Team Ever?

Euro 2008, World Cup 2010, and now Euro 2012 champions. Spain’s 4-0 demolition of Italy in yesterday’s final in Kiev secured their third consecutive major tournament victory in the last four years. The question many are asking today is whether La Roja is the greatest team in the history of football.

Euro 2008, World Cup 2010, and now Euro 2012 champions. Spain’s 4-0 demolition of Italy in yesterday’s final in Kiev secured their third consecutive major tournament victory in the last four years. The question many are asking today is whether La Roja is the greatest team in the history of football.

Hundreds of millions of TV viewers watching the final in pubs, homes, and public venues around the world witnessed Spain’s best performance of the Euros. Propelled by Xavi’s sudden resurgence and Del Bosque’s flawless tactics, lineup, and game management, the Spanish tiki-taka approached a near-perfect synthesis of art and science. Meanwhile Italy’s tired legs and coach Prandelli’s naive decision to deploy 2 strikers, no defensive midfielders, and field injured Chiellini, De Rossi and even Motta (as a final substitute!) exposed the substantial qualitative gap separating the two finalists.

While my emotional wounds from enduring such a hideous hiding are still raw, I’m interested in what people have to say about how Spain 2008-12 compares, say, with Brazil 1970? Germany 1972-74? Or even Uruguay 1924-1930 and Hungary 1950-54 if we delve into a radically different media era? Should we consider club teams too? Real Madrid 1955-60, Ajax 1971-73, Milan 1989-90, and Barcelona 2009-2011 immediately come to mind.

Here are my top 5:

1. Uruguay 1924-30 (winners of 1924 & 1928 Olympics and 1930 World Cup)

2. Spain 2008-2012

3. Brazil 1970 (good case for the best ever, but won only one title)

4. Hungary 1950-54 (undefeated, 42 wins and 7 draws).

5. Barcelona 2009-11 (FIFA Club World Cup: 2009, 2011; Champions League: 2008–09, 2010–11; UEFA Super Cup: 2009, 2011; La Liga: 2008–09, 2009–10, 2010–11; Copa del Rey: 2008–09, 2011–12; Supercopa de España: 2009, 2010, 2011)

What do you think? Share your rankings in the comment section!

Afritalians: Past is Prologue

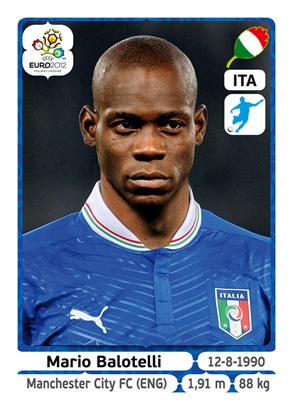

The Africanization of Italy may have started 2200 years ago as Hannibal of Carthage led his troops and elephants across the Alps on the way to Rome, but Mario Balotelli’s two-goal performance in Italy’s defeat of Germany in the Euro 2012 semifinal may be mainstreaming it.

The Africanization of Italy may have started 2200 years ago as Hannibal of Carthage led his troops and elephants across the Alps on the way to Rome, but Mario Balotelli’s two-goal performance in Italy’s defeat of Germany in the Euro 2012 semifinal may be mainstreaming it.

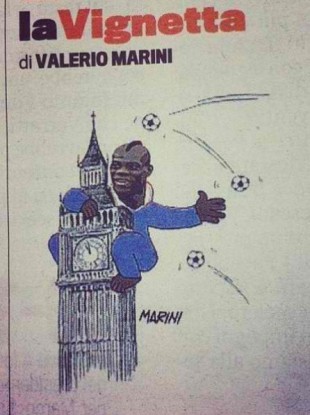

Italians across the political spectrum are gushing in their praise of the 21-year-old striker. “Pride of Italy!” screamed the web site of La Gazzetta dello Sport, which earlier in the week had printed an insulting cartoon of Balotelli as King Kong by Valerio Marini (see below). (Despite an outpouring of criticism from readers and on social media, the paper could only muster this sad excuse for an apology: “if certain readers found the cartoon offensive, we apologize.”)

Earlier in the tournament Balotelli had won accolades for his acrobatic overhead strike against Ireland and for his impeccable penalty which opened the shootout against England (scored against Man City teammate Joe Hart). Now, on the eve of the final against Spain in Kiev, ordinary Italians and the media are comparing Balotelli to Gigi Riva, Totò Schillaci, and Gianluca Vialli — illustrious Azzurri of the past who transcended the football pitch to become popular icons of national culture. A big and very noticeable difference between Super-Mario and his predecessors, of course, is that Balotelli is black — the Palermo-born son of the Barwuahs from Ghana who was adopted by the Balotellis of Brescia. He is the first Afritalian football superstar.

Super-Mario’s central role in potentially ushering in a new phase in the Africanization of Italy is reflected in Italian media stories highlighting how Mario is like you and me: he loves football, family, pizza, and hanging out with his friends. In a country where mothers are sacred and where the Virgin Mary is venerated almost as much as her more famous son, Mario’s loving embrace of Mamma Silvia in the stands at the Warsaw stadium shot an arrow into the heart of every Italian. “Boastful and ‘mammone’, Balotelli represents the prototype of the Italian,” wrote Il Giornale, a conservative paper owned by Silvio Berlusconi’s brother, Paolo.

And Balotelli is not an isolated case; he’s not even the only Afritalian in the Euro squad. Sitting on the reserves’ bench is 24-year-old Angelo Obinze Ogbonna (at left), a central defender who plays his club football for Torino. Born in Cassino, near Rome, of Nigerian parents, Ogbonna was recruited into the Torino youth academy at age 14 and played his first serie A match at 19. Like Balotelli, Ogbonna speaks Italian without a trace of accent. The experiences of Super-Mario and Ogbonna open up an opportunity to consider the history of Afritalian footballers.

And Balotelli is not an isolated case; he’s not even the only Afritalian in the Euro squad. Sitting on the reserves’ bench is 24-year-old Angelo Obinze Ogbonna (at left), a central defender who plays his club football for Torino. Born in Cassino, near Rome, of Nigerian parents, Ogbonna was recruited into the Torino youth academy at age 14 and played his first serie A match at 19. Like Balotelli, Ogbonna speaks Italian without a trace of accent. The experiences of Super-Mario and Ogbonna open up an opportunity to consider the history of Afritalian footballers.

Let’s start with Claudio Gentile. He was born in Tripoli, the son of a Sicilian father and a Tripoli-born mother possibly of Italian background, and grew up playing street football in Libya before moving to Como in 1961 with his family. Nicknamed “il libico,” Gentile had his best years at right back for Juventus and Italy in the 1970s and early 1980s, forming with Dino Zoff, Antonio Cabrini, and Gaetano Scirea one of the stingiest defensive lines of all time. Gentile’s ferociously effective man-to-man marking of Maradona and Zico in the 1982 World Cup, which Italy won, has become the stuff of legend.

We had to wait nearly two decades for the next Afritalians to make an appearance in the national team. In 2001, Fabio Liverani, the Rome-born son of a Somali mother and Italian father, made his international debut in a friendly against South Africa. Despite a solid career as a midfielder with Lazio, Fiorentina, and Palermo, Liverani only played twice more for the Azzurri. Around the same time, Matteo Ferrari, the Algeria-born son of an Italian father and a Guinean mother, played eleven times in the heart of Italy’s defense. Prior to Balotelli’s success, Ferrari had held the record for most international appearances for an Afritalian. (He now plays for the Montreal Impact in MLS.)

There are other players of African blood in Italian football. Among them, Stephan El Shaarawi, Stefano Chuka Okaka, and Fabiano Santacroce (of Afro-Brazilian/Italian parentage) have been capped at junior level. There is also a female Afritalian: left back Sara Gama (at right), who also earned the distinction of becoming the first Afritalian woman to captain the U-19 national team, and leading them to the 2008 European title.

There are other players of African blood in Italian football. Among them, Stephan El Shaarawi, Stefano Chuka Okaka, and Fabiano Santacroce (of Afro-Brazilian/Italian parentage) have been capped at junior level. There is also a female Afritalian: left back Sara Gama (at right), who also earned the distinction of becoming the first Afritalian woman to captain the U-19 national team, and leading them to the 2008 European title.

Mauro Valeri, a sociologist and author of La Razza in campo: Per una storia della Rivoluzione Nera nel calcio (EDUP, 2005) wonders if the increasing presence of black players at junior and senior level is “perhaps a sign of a transformation underway, of the affirmation of a Black Revolution [in football] that for more than a decade has been unfolding in Italy.” While structural changes would be necessary for such a shift to be lasting and meaningful, social perceptions of Afritalians may be changing thanks to Balotelli’s sudden popularity. In a grim age of austerity and structural adjustment, Italians seem eager for another taste of Super-Mario-triggered football euphoria.