With the African Nations Cup about to kick off this weekend in Equatorial Guinea and Gabon, it’s time to put the spotlight on Yaya Touré, the Ivorian international and Man City midfielder. In this part of a longer interview produced by his new endorser — Puma, an expanding commercial force in African football — the best-paid player in the English Premier League reflects on growing up in Ivory Coast, learning the game in Bouake, and then moving to big-time football in Abidjan.

Thanks to Tom McCabe for telling me about this interview.

Author: Peter Alegi

Spotlight on African Coaches: Part 2

Photo: Breakthrough Chiparamba girls football team, 20 July, 2011, Olympic Youth Development Center, Lusaka, Zambia. Courtesy of Hikabwa Chipande.

Training and Developing Coaches in Southern Africa: Licensing and Administration

Guest Post by Hikabwa Decius Chipande (@HikabwaChipande)

Football is the most popular sport in southern Africa but there are few qualified coaches at all levels. Prior to 2010 most top league clubs in southern Africa were coached by people without even a basic qualification.

One major problem is that Southern African countries have a haphazard approach to coach education. What had been happening until recently was that any person could come to the region, conduct a coaching course for a few days, and declare the participants as coaches with questionable certificates of limited value. It has been, therefore, very difficult to know the actual capabilities of local coaches and their qualifications because there had been no set benchmarks. South Africa is an exception in that it has the South African Qualification Authority (SAQA), although its effectiveness remains debatable.

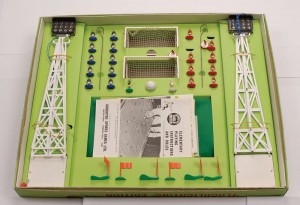

Memories of a Subbuteo Player

After many, many years, I recently played Subbuteo again. It was such a blast that I’m starting a series of posts on the world’s greatest football game ever invented. My older brother, who taught me how to play, kicks off.

By Daniel Alegi

Rome, Italy, Christmas 1973: I finally got Subbuteo, the new English game everyone was talking about. It was the “Continental” set (see photo below); the box said the name was pronounced “sub-BEW-teo.” 20,000 lire ($15) got you a green cloth pitch, two white floodlights 13 inches high with 9-volt batteries, two plastic goals with brown nets, two balls, two goalies with a handle-rod and two teams in white shorts: one with red shirts, the other with blue.

“Italy – Russia!” I said. “Como-Varese!” said my brother from the height of his 18 months’ seniority. Their kits are almost identical, but would you rather make your debut in the Christmas snow at Moscow’s Lenin Stadium or in a Serie B derby in the Po Valley fog? Our first flicks were backed by our grandfather in the armchair snoring away. Cloth pitch on the carpet, improvised rules. Then during lunch dad stood up and stepped on everything (how could he miss a 4.5ft x 3ft pitch?). On the ground lay decapitated, amputated, crushed players. Only six survived this massacre, one of them a goalkeeper. And so with this ill-fated 1973 debut, played with only one goal, Subbuteo entered our house forever.

Bundesliga Blooper

Stryker-Indigo New York, a private multi-media film and print production company, has announced the acquisition of a major collection of 1950s-1960s 8mm and 16mm soccer films.

Stryker-Indigo New York, a private multi-media film and print production company, has announced the acquisition of a major collection of 1950s-1960s 8mm and 16mm soccer films.

The film footage, featuring both university and international teams playing in American cities, contains rare home movie images of the history of the game in the United States. For example, there is footage of the first leg of the 1961 U.S. Open Cup Final between United Scots of Los Angeles and Ukrainian Nationals of Philadelphia at Rancho La Cienega Stadium in LA (now Jackie Robinson Stadium).

According to the Stryker-Indigo web site, its Futbol Heritage Archive houses nearly 9,000 historic photographs, slides, newspaper clippings, postcards, trophies, jerseys and artifacts. Following the closure of the US Soccer Hall of Fame in Oneonta, NY, researchers have lost access to an archive of more than 80,000 items, including the North American Soccer League archive and the 1994 World Cup archive. It is hoped that private collections such as Stryker-Indigo’s film footage will be made accessible to soccer researchers and aficionados so that the history and culture of the game can be properly recorded and disseminated.

***

Thanks to David Wallace for inspiring me to write this post.

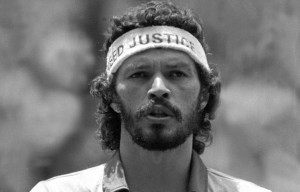

Socrates of Brazil is Gone

Barcelona, 5 July 1982: Paolo Rossi had just headed in an Antonio Cabrini cross to put us up 1-0 against Brazil in the last game of the second group stage of the 1982 World Cup. My friend Fabio and I, football-obsessed youngsters, sat wide-eyed on the floor of an impossibly crowded living room in a relative’s home outside Pesaro, in the hills of the Marche region of Italy. A few days before we had been part of a spontaneous street carnival with tens of thousands of fellow Romans celebrating our victory against Maradona’s Argentina. Rossi’s goal suddenly made a miracle possible: beat Brazil and earn a place in the semifinals.

Five minutes later, a Brazilian Doctor made an incision that surgically removed the optimism of hope. Socrates, we knew from watching Corinthians games on Teleroma 56 (a local station), had a penchant for embarrassing defenders with graceful pivots on the ball and elegant heel passes. To say nothing of goalkeepers humiliated by his swerving free kicks and shots from impossible angles.

That hot July afternoon on the pitch of Español’s Sarria Stadium, Socrates received the ball in midfield, carried, dished it off to Zico and continued his run forward. With the outside of his right foot, Zico quickly sliced a delightful pass to a streaking Socrates in the box. Socrates took a simple touch and appeared to be running out of room on the right side of the 6-yard box. Where most players would square the ball back into the middle of the box for a teammate to run on and strike at goal, Socrates instead took a precise near-post shot that faked Dino Zoff out of his shorts: 1-1. No! He didn’t just do that?! Watch it here. (Italy went on to win the game 3-2 and the World Cup.)

After the 1982 tournament, Corinthians traded Socrates to Fiorentina so we got to appreciate the fullness of this grandiose footballer for many years. Even Juve fans like me, whose contempt for La Viola is unrestrained, became fond of “Tacco d’Oro” — the Golden Heel — the tall, lanky, bearded midfielder with the long curly hair who added so much spectacle to Serie A in the age of Maradona, Platini, and Falcao.

A decade later, I found myself still learning from Socrates but in a completely different context. While teaching one of the first undergraduate courses on soccer ever taught in an American university, my students and I discussed Socrates’s role in Corinthians Democracy, a movement that helped propel democratic change in Brazil in the early 1980s. How many professional athletes would threaten to retire, as Socrates did in 1982, if a conservative businessman were to take the reins of a popular team?

So it was with profound sadness that I learned of Socrates’s passing at the age of 57. The official cause of death was “septic shock from an intestinal infection” according to a São Paulo hospital statement. Like Garrincha, Brazil’s most loved footballer, Socrates was an alcoholic. The rum-like cachaça had become his vital fluid. As Socrates candidly put it in an interview: “This country drinks more cachaça than any other in the world, and it seems like I myself drink it all.” We all battle our demons.

As the South Africans say, “Hamba kahle” brother Socrates. Your love of the game and commitment to social justice will never be forgotten.

Suggested reading:

Matthew Shirts, “Socrates, Corinthians, and Questions of Democracy and Citizenship,” in Joseph Arbena, ed., Sport and Society in Latin America: Diffusion, Dependency, and the Rise of Mass Culture (New York: Greenwood Press, 1988), pp. 97-112.

Simon Romero’s poignant obituary of Socrates in the New York Times is here.

Golatoo! What Maradona Taught Me

Juan Manuel Olivera scores the winner for Al Wasl against Al Ain in the UAE league. Al Wasl’s head coach, Diego Armando Maradona, must be pleased to see his lessons translated into magical “golatos.”