The English Premier League is an obsession for millions of African fans. Author and fútbologist David Goldblatt recently traveled to Lagos, Nigeria, to find out what this cultural phenomenon looks like and why there is such deep reverence for Arsenal, Manchester United, Chelsea, Spurs, and . . . Bournemouth.

In a newly released piece for Bleacher Report, Goldblatt hears from Emeka Onyenufuro, founder of Arsenal Nigeria, who tells him that “Monday to Friday lunchtime, I’m working in my job [as a manager in the power industry], but from Friday afternoon to Monday morning, it is all Arsenal.”

The quality of EPL play and the excitement of watching some of the world’s best players, including N’Golo Kanté, Victor Moses, Yaya Touré, and many other African superstars, partly explains the intensity of local passion for and dedication to the EPL. But another explanation is that the middle-class Nigerian men at the heart of this piece have willingly capitulated to the EPL’s “attention merchants” (Tim Wu docet): “It’s the branding. . . it’s just so professional,” a fan explains.

The author takes us into various public viewing spaces where the South African-owned satellite provider DSTV beams in live games, highlights, and talk shows that collectively stoke the obsessive compulsions of the Nigerian EPL fan. When not watching matches (and praying that frequent power cuts don’t ruin crucial moments in the broadcast), the lads follow their favorite clubs on social media for several hours a day.

The piece also features a fascinating description of the Socialiga, a football and basketball league and “social space to network with their peers, flirt and raise some money for charity.” It left me wanting to know even more about this astonishing kind of grassroots social entrepreneurship.

The Nigerian photographer Andrew Esiebo’s images complement the prose quite beautifully. And Esiebo’s camera does not lie: David Godlblatt seemed most at home in Lagos among his Spurs Nation mates (see photo above).

Read the full article here.

Category: Fútbology

Is there an implicit racial bias in Major League Soccer and other U.S. leagues?

A piercing SB Nation story this week grappled with the implications of a recent study‘s disturbing findings “that black players are 14 percent more likely to be called for cautions than their non-black counterparts.” The study by Paste magazine also found that “black players are [. . .] more than twice as likely to receive red card ejections.”

In the article, I share my thoughts on this important issue with the SB Nation reporter, Tyler Tynes. I point out that “while finding empirical data is difficult, there’s plenty of soft and hard discrimination to believe that bias can take hold in refereeing. American soccer is not excused.” In fact, officiating bias can be understood as part of a broader pattern of racism in soccer, in the U.S. and internationally, one characterized by the practice of “stacking,” the presence of very few black coaches on the sidelines, and multiple forms of racist fan behavior.

“It can’t be denied,” I say in the piece. “Racism in soccer, in Europe certainly, is very real. And, regrettably, despite all the progress that’s been made in terms of messaging and tolerance in local football culture, it’s still there. And everybody knows it.”

But don’t take my word for it, click here to read the full story.

“Beyond the Pitch” is a riveting BBC World Service radio documentary that explores the close links between the “beautiful game” of football and the “dirty game” of politics in multiple African countries.

Produced by Farayi Mungazi and Penny Dale, the 50-minute feature aired on the eve of the 2017 Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) in Gabon, which marks the 60th anniversary of the continent’s most prestigious sporting event.

The documentary opens with Nigeria’s boycott of AFCON 1996 in South Africa. The last-minute withdrawal of the Super Eagles came in retaliation for President Nelson Mandela’s scathing criticism of Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha’s regime, which in November 1995 had executed author Ken Saro Wiwa and eight more Ogoni environmental activists in a sham trial.

The next segment is captivating and among the most historically significant. It tells the story of how football helped Algeria’s struggle for independence from France through mesmerizing interviews with Mohamed and Khadidja Maouche. He was a young professional footballer in France in the late 1950s, but the newlyweds were also members of the National Liberation Front (FLN), the main Algerian liberation movement. The couple reveals how they secretly worked together to facilitate an exodus of Algerian-born footballers from their French clubs to play for the FLN “national” team. “No-one knew I was married to Maouche,” Khadidja says. “They would just be told a FLN activist wanted to speak to them. I would talk to them individually to say: ‘It’s an order, that’s it,’ and they all agreed.” In 1960 Mohamed Maouche eventually joined the FLN team, which played matches in front of large crowds in North Africa, the Middle East, East Asia, and Eastern Europe. “We were the first ambassadors of the revolution and the Algerian people,” he recalls with profound emotion half a century later.

Burundi’s current President Pierre Nkurunziza, a qualified football coach and owner of Hallelujah FC, is mentioned as a bridge to a terrific interview with Dr. Hikabwa Chipande, an historian and Michigan State University alumnus (PhD, 2015). Now a lecturer in African history at the University of Zambia, Chipande brings the BBC reporter through the archives in Lusaka where he conducted doctoral research on the history of Zambian football. As they look at sources documenting former president Kenneth Kaunda’s passion for and involvement in the game, Chipande points to a 1974 photograph of Kaunda serving food to the national team—quite an endearing, populist image. Mungazi then travels to Luanshya, on the Copperbelt, to talk football and politics with Dickson Makwaza, one of the players served by Kaunda in 1974, and with 91-year-old Tom Mtine, a legendary football administrator.

In the second half of the documentary we leap ahead to AFCON 2010 in Angola. The Togo national team bus was targeted by armed separatists from the enclave of Cabinda at the border with the Republic of Congo: “probably the most dramatic moment ‘off the pitch’ in the history of the Africa Cup of Nations,” Mungazi says. The armed attack killed two men and wounded several others: “one of the worst experiences I’ve had in my life,” said Togolese striker and English Premier League veteran, Emmanuel Adebayor.

The last time Uganda qualified for AFCON was in 1978 when the infamous Idi Amin was still in power. A local academic and former national team players explain how Amin, a keen boxer himself, bankrolled sports during his dictatorship (1971-79) to boost nationalism and also as a weapon of mass distraction. But we also hear of the traumatic experiences of John Ntensibe and Mama Baker. The former was imprisoned and forced to load bodies onto trucks after scoring the winning goal for Express FC against the army team, Simba, while Baker, a devoted Express supporter, was arrested twice for little more than being Uganda’s biggest soccer fan.

Fast forward again to the 21st century: we hear about George Weah, Africa’s only World Player of the Year (1995), who launched a career in politics in Liberia after retiring from the game. Weah lost a presidential election in 2004 (to future Nobel Peace laureate Ellen Sirleaf Johnson), but recently won a Senate seat and may run again for his country’s highest office.

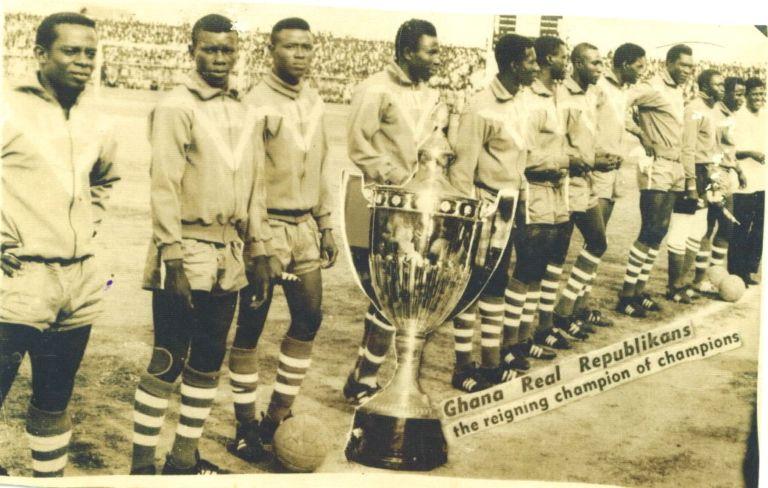

The final chapter in the story of the links between politics and football focuses on Ghana. There, top clubs Accra Hearts of Oak and Kumasi Asante Kotoko have long been entangled in party politics and presidential contests. Veteran Ghanaian reporter Kwabena Yeboah also describes the emergence of Real Republikans, a super club of the 1960s closely connected to President Kwame Nkrumah. Subsequent regimes in Ghana, it is noted, used the men’s national team, the Black Stars, to strengthen their popularity and “perpetuate their reign.”

As a scholar who has been writing about African football history, culture, and politics for a long time, I found Farayi Mungazi and Penny Dale’s “Beyond the Pitch” documentary to be finely researched and evocatively presented through African voices. The producers did well to carefully bring out the game’s contradictory capacity to be a force for empowerment and disempowerment. What a great way to get ready for the upcoming 2017 AFCON in Gabon. And what a wonderful resource for teaching and research.

Click here to listen and download the podcast version of the documentary.

The AmaXhosa Maradona

The story of Abongile Elton Qobisa, also known as the “Xhosa Maradona,” has not been covered by ESPN, SKY, SABC, or FIFA media. But Tarminder Kaur, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of the Free State in South Africa, is determined not to allow us to forget him.

On October 27, the moving tale about Qobisa will be the subject of the Football Scholars Forum’s 37th session. Kaur’s paper is based on ethnographic fieldwork in the Western Cape region. It engages critically with “sport-for-development” discourses and its limits, a topic Pelle Kvalsund and Hikabwa Chipande, among others, have written extensively about on this blog.

“In contemporary South Africa,” Kaur writes, “soccer is discursively portrayed as a tool for ‘development’ and socialization of ‘black’ youth living in structurally constrained conditions. Indeed, it is the stories of ‘rags to riches’ through sport talent and success that continue to spark imagination for possibilities through soccer for the marginalized and those in need of ‘development.'”

The paper deftly critiques these discourses by presenting an intriguingly diverse cast of male characters. Readers are introduced to passionate township players, devoted coaches, hardcore fans, and well-meaning patrons of the game. Through numerous oral interviews and personal observations, the study reveals the multiple ways in which young black men from humble circumstances “create and find meaning in practices of soccer.” In a context of economic insecurity and social instability, the author highlights how “talent and opportunities in soccer were both a gift and a curse for the amaXhosa Maradona.”

To participate in the online forum, please visit the FSF website.

Click here for the Sport in Africa web dossier compiled by the African Studies Library at Leiden University.

Politics and Soccer in the Middle East

The Football Scholars Forum opened its 2016-17 season on September 19 with a discussion of James Dorsey’s long-awaited new book, The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer.

A journalist and Senior Fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University, Dorsey’s blog “(has) become a reference point for those seeking the latest information as well as looking at the broader picture” on Middle East soccer and politics, according to FSF member Alon Raab, who teaches at the University of California Irvine.

Twenty participants spread out across North and South America, Africa, Europe, and, naturally, the Middle East engaged in a lively online discussion with the author. Dorsey began by describing the origin of the project and a disclaimer that he is neither a player or fan of the game. The book, he stated, is about politics, not soccer. But he immediately qualified this quasi-heretical statement (among fútbologists, at least) by stressing that sports and politics are always linked, though at different levels of intensity depending on the place and time.

Dorsey emphasized the importance of young Egyptian ultras in the overthrow of Mubarak and of stadiums as spaces of mobilization, dissent, and censorship. A particularly interesting thread of the forum was the focus on social media as scholarly sources–“cyber-ethnography”–and also as an invaluable space for public discourse.

Prompted by new questions, Dorsey shared his thoughts on gender issues; the limited influence of “Muscular Islam” in its diverse interpretations (from conservative to liberal) on the region’s football culture; racial and ethnic discrimination; and how the failed July 15 coup in Turkey means soccer fans have been caught in the wider web of repression carried out by the Erdogan regime.

Despite the grim status quo for people and football in war-ravaged Syria, Dorsey closed on an optimistic note, arguing that we are at the beginning of a long process of potentially positive change in the Middle East. Time will tell, but what is certain is that the game will continue to serve “as an arena where struggles for political control, protest and resistance, self-respect and gender rights are played out.”

Click here for an audio recording of the session.

For information about the next Football Scholars Forum on October 27, please visit footballscholars.org.

Image: Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C.

Image: Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C.

Cross-posted from The Allrounder

[First published on November 13, 2014]

We don’t just watch sports – we speak and hear sports. To find out how language shapes our lives as fans, we asked some of our writers to tell us about the ways that people talk sports in English and their native languages. Kay Schiller hails from Munich, fellow historian Peter Alegi grew up in Rome, media scholar Markus Stauff lives in the Netherlands, and sociologist Pablo Alabarces teaches at the University of Buenos Aires. Together, they offer a Rosetta Stone of sports talk.

You’ve all lived for a time in English-speaking countries. Did anything in particular strike you – say, the first times you went to a stadium or watched a match on television – about the ways that native speakers of English talk about their sports?

Kay Schiller: I have lived in the UK since 1997. One of the things that struck me as a non-native speaker when going to see Chelsea, Spurs, Liverpool, ManU, or, more recently, Blackburn Rovers was that I had a tremendously hard time understanding the terrace chants, despite being quite fluent in English. I suppose that this is similar to what English fans experience when they attend a Bundesliga match.

Thankfully, there are now websites that explain what you hear in the stadium. You can learn that Blackburn Rovers fans at Ewood Park have several profane chants for Burnley, such as “Burnley are s**t s**t s**t , they always gonna be s**t.” One major difference with Germany is that while this kind of folklore can be found in the supporters’ curves of stadia, you wouldn’t hear otherwise respectable-looking people participating in chants like these – or middle-aged ladies calling the referee a c***.

I’m not sure what this suggests about the different football cultures of England and Germany, or culture more generally, but I find it worthy of note. Perhaps it’s reassuring that even with all-seater stadia and the continuous jacking-up of gate prices in English football, some things do not change.

Peter Alegi: At venerable Fenway Park in Boston, sitting in the bleachers with my dad (obstinately wearing a Yankees cap), the usual chant we heard was: “Yankees suck!” At New Haven Coliseum, where my older brother and I followed minor league ice hockey, it was: “Shoot the puck!” At basketball and American football games, giant electronic scoreboards demanded chants of “Deeeeee-fe-nse!”

This was a world away from the Italian football stadiums and basketball arenas I grew up with.

What first struck me in the U.S. was a lack of spontaneity in the language of fans at the grounds. The PA announcer, the scoreboard, and recorded music directed the orality of the crowd. Maybe this was because of the corporate nature of American sports, with its top-down manufactured stadium experience that transforms fans into consumers. It’s also hard to chant and sing when spending so much time, money, and energy eating and drinking during games. In any case, the second thing that hit me about the U.S. context was the lack of creativity in the language. Much of the spoken word among fans, chants and commentary alike, seemed very direct and not terribly imaginative, a bit like the English language!

In Italy, our oral culture at the stadium was far more creative. I remember sitting in the stands listening to self-appointed bards who would rise to recite absorbing monologues in the vernacular (dialects are hugely important and richly diverse in Italy). These men (rarely were they women) explained the causes of our striker’s inexplicable impotence or the reasons for the referee’s situational ethics. The language was often metaphorical, indirect. The best insults were the ones delivered with a perfect balance of grit, humor, and linguistic dexterity. Even my intellectual Roman mother, with a PhD in Italian literature, relished such vulgar poetic performances (“vulgus” in Latin means ordinary people, after all). This creative genius came through in the songs we sang. Fans developed an art of crafting lyrics and combining them with a dizzying range of musical sources: classical (Beethoven’s “Ode To Joy” was a favorite); operatic (Verdi, of course); patriotic compositions (“La Marseillaise”); marches (John Philip Sousa!); folk/traditional (“La Società dei Magnaccioni,” “O Sole Mio,” and “Auld Lang Syne”); partisan resistance (“Bella Ciao”), and loads of pop (from “Yellow Submarine” to Antonello Venditti’s “Roma, Roma, Roma”).

Eventually, I came to appreciate the comfort and safety of U.S. stadiums and arenas. But to this day, their canned and often lifeless aural culture makes me nostalgic of home.

Click here to read on.