The Football Scholars Forum, an international online think tank, convened on November 14 to discuss Football in the Middle East. The conversation focused on a special issue of the academic journal Soccer and Society, edited by Alon Raab and Issam Khalidi. The group began by noting that while football has been a critical force in broader political and cultural developments in the region, there is little institutional support for studying the game in the Middle East.

The Football Scholars Forum, an international online think tank, convened on November 14 to discuss Football in the Middle East. The conversation focused on a special issue of the academic journal Soccer and Society, edited by Alon Raab and Issam Khalidi. The group began by noting that while football has been a critical force in broader political and cultural developments in the region, there is little institutional support for studying the game in the Middle East.

The ensuing 90-minute discussion demonstrated the value of scholarly collaboration and research on the game. The group explored a dizzying number of topics and territories, including football as a source of unity and hope and as a site of political and ideological conflict; the 2022 World Cup in Qatar; soccerpolitics in Turkey; sport and Islamism; Palestinian and Iraqi Kurdish women’s teams; and football films and poetry.

For a Storify Twitter timeline click here.

Download the mp3 of the session here.

Category: Fútbology

Football and Independence in Zambia

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

LUSAKA—On a rainy Friday evening at the Pamodzi Hotel, Zambia Open University Professor Ackson Kanduza, president of the Southern African Historical Society, convened a forum based on my paper “Football and Independence in Zambia: A Political and Social History 1950s-1964.”

Part of my doctoral research on colonial and postcolonial Zambian football, the paper draws on archival, newspaper, and oral sources to argue that the changing culture of the African game influenced the anti-colonial nationalist struggle by fighting racial segregation and promoting African leaders to highly visible and prestigious administrative positions before independence.

In the early 1960s, colonial racism in then-Northern Rhodesia was still intense. Segregation kept Africans out of European-owned shops and forced black customers to shop through a window instead; Africans were not allowed to enter whites-only train carriages and buses; and jobs paying higher wages were reserved for whites.

But in 1961-62, black and liberal white businessmen founded the nonracial (racially mixed) National Football League. A black man, Tom Mtine, was named chairman of an otherwise white-dominated league executive. Two years prior to independence, the NFL permitted black players to be on the same teams as whites, and Africans were also allowed to represent the territory in international competitions. The emergence of black administrators like Tom Mtine and the game’s function as a “neutral” cultural form among people speaking 73 languages helped to assert black power as well as a sense of Zambian-ness that cannot be ignored in the history of Zambia.

An audience of both academics and members of the general public posed interesting questions and offered constructive comments. Most participants agreed with me that these sporting events signified an important step towards political freedom. Some noted that as Zambians celebrated their country’s 40th independence anniversary, my historical evidence about black leaders in football and the hosting of an international football tournament in 1964 to celebrate the nation’s birth would be highly appreciated by millions of Zambians. The discussion also grappled with the seemingly contradictory evidence that the British believed the game to be part of the “white man’s burden” while local people used it to fight colonial oppression.

“I did not know that our football has such a rich history,” said Pride Mwaanga; “I was wondering about the connection between football and independence, but now it makes sense!” Other participants asked why this rich history of Zambian football has not yet been explored. Echoing the conclusions of Marissa Moorman’s recent history of music and nationhood in the musseques (shantytowns) of colonial Luanda, Angola, audience members highlighted how, unlike anti-colonial political leaders, Zambian football administrators and players’ contributions to building the Zambian nation are not recognized in typical historical accounts.

Participants also stressed the need to publish biographies of past footballing greats such as “Ucar” Godfrey Chitalu, Dickson Makwaza, John “Ginger” Pensulo and many, many others. Professor Moses Musonda, Zambia Open University Deputy Vice Chancellor, pointed out that we need more scholars to research and write the history of football in Zambia, otherwise we are going to lose this valuable past.

Other interesting contributions came from Mrs. Kanduza and, again, from Prof. Musonda, who both gave testimonies of how they experienced leisure activities in welfare centers during the colonial era. These social centers played a critical role in the development of football. Prof. Musonda stated that Europeans enforced separate social institutions such as welfare halls to make sure that young Africans did not have the opportunity to challenge young Europeans in sport. Ironically, the same welfare centers and sporting facilities helped African men and women build their self-esteem and were later turned into avenues for political agitation.

Prof. Kanduza concluded the event by pointing out that a goal of the Zambia Open University is to organize forums that give opportunities to listen to unheard local voices. He highlighted how the research and discussion of “Football and Independence in Zambia” captures voices and conveys the historical experiences of African people through the prism of sport. The evening ended with a promise to organize more of these lively and insightful sessions in the near future.

—

*Hikabwa Chipande is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at Michigan State University. He is currently in Lusaka researching the social, cultural and political history of football in colonial and postcolonial Zambia. Follow him on Twitter at @hikabwachipande

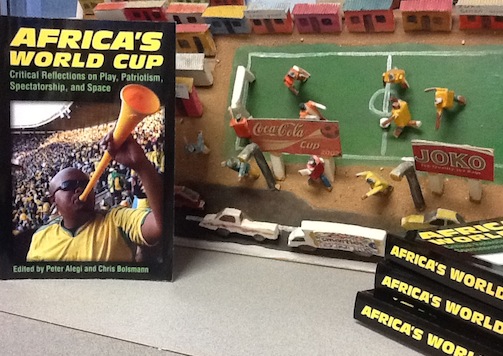

The Football Scholars Forum, an online fútbol think tank I co-founded at Michigan State University, recently launched its 2013-14 season. On October 24, FSF held a lively discussion of Africa’s World Cup: Critical Reflections on Play, Patriotism, Spectatorship, and Space, a newly published collection I edited with Dr. Chris Bolsmann, a South African sociologist based in the UK.

The 90-minute event opened with a consideration of the book’s attempt at blending scholarly and journalistic approaches to exploring the game and its broader implications. The editors and several chapter authors in attendance talked about the process of writing and editing, as well as their experience working with an academic press on a topic with potentially broad appeal.

The book, much of it written in the first person as a loving critique of the 2010 tournament, demonstrates how the FIFA World Cup story is entangled in a web of national and international politics, sporting culture, and global capitalism. Many interventions linked South Africa 2010 to Brazil 2014, particularly through the public financing of expensive and unsustainable new World Cup stadiums in countries with dysfunctional schools and hospitals and high rates of poverty and inequality. The online conversation also featured Luis Suarez’s handball against Ghana and the contradictory legacies of this “African” World Cup.

Participants logged in from half a dozen countries in North America, South America, Africa, and Europe. In attendance: Andrew Guest, Chris Bolsmann

, Christoph Wagner

, David Patrick Lane,

David Roberts,

Derek Catsam,

Jacqueline Mubanga,

Raj Raman,

Orli Bass

, Rwany Sibaja,

Laurent Dubois

, Achille Mbembe

, Jordan Pearson, Sean Jacobs, and Alex Galarza (all via Skype); and Liz Timbs,

Dave Glovsky,

Alejandro Gonzalez, and

Peter Alegi (in East Lansing).

For a Storify Twitter timeline of the event click here.

The audio recording of the discussion is freely available here.

The next Football Scholars Forum event on November 14 will focus on Soccer in the Middle East, a special issue of the journal Soccer and Society (2012), edited by Alon Raab and Issam Khalidi.

Football 150: Conference Report

Guest Post by Dr. Matthew L. McDowell

The new home of the National Football Museum, the Urbis Building in Manchester, was the site of an international conference on September 2-4, 2013, celebrating the 150th anniversary of England’s Football Association. The event welcomed a group of around sixty speakers and an even larger group of delegates from different disciplines interested in the past, present, and future of football: its culture, its finances, its development, and its governance.

The varied affiliations of the participants made for some rather productive tension: critics of world football’s leaders and patrons rubbed shoulders with officials from the FA and UEFA, and no words were minced. Sir Trevor Brooking’s appearance at the outset of the conference, and Karen Espelund’s keynote address on the final day, were sandwiched around acclaimed author David Goldblatt’s second-day keynote: a brilliant, scathing, and often surreal account of FIFA in relation to the Brazilian riots of this past summer, which occurred while the Confederations Cup was staged in the country. (Those who were at the address will never think of AC/DC’s “Hell’s Bells” in the same way again.) All in all, it made for a highly enjoyable three days, and the National Football Museum (especially Dr. Jane Clayton and Dr. Alex Jackson) and the University of Central Lancashire’s International Football Institute pulled out all of the stops to ensure that all of us working within the broad continuum of “football studies” felt at home.

After Brooking’s interview with UCLan’s John Hughson – one of the driving forces behind the gathering – Tony Mason of De Montfort University, a renowned expert on English football’s history, introduced us to previous commemorations of the FA’s anniversary: some lavish, some passing barely noticed. I attended various sessions afterwards. Naturally, I leaned toward history: Tony Collins, Roy Hay, and Gavin Kitching formed an excellent panel advocating more research into what Collins called the “primordial soup” of football in the pre-Association era. The term “football,” as both Hay and Kitching stated, was representative of a very broad church prior to 1850, and was not confined to the “public school” sphere. Afterwards, I attended a session on the history of ‘soccer’ in the United States, with my native New Jersey finding its way into both Brian Bunk’s and David Kilpatrick’s papers: Bunk discussed the football-playing circle of the mid-nineteenth century Princeton University, while Kilpatrick discussed the colorful, controversial and recently-revived New York Cosmos, whose 1970s’ home was the NFL’s Giants Stadium. The “Nostalgia and Design” panel, which featured Jean Williams, Graham Deakin, Ffion Thomas and Chris Stride teased out the meanings in some of football’s most iconic (and, in the case of Shoot and Goal magazines, not-so-iconic) images through various media.

The second and third days featured their fair share of highlights. Notable among them was Gary James, who gave us a glimpse into late-nineteenth/early-twentieth century football in Manchester, a subject long neglected by academic historians. Matthew Klugman, Svenja Mintert, and Jessica Richards, meanwhile, discussed their own pioneering research, and their attempts to examine the emotions, desires and suspicions of “the fans” in a wide variety of time periods, places, and guises. (Richards, whose ethnographic research examines the match-day rituals and gender performance of Everton supporters, candidly discussed the risks associated with field work.) Meanwhile, “The Role of the Individual,” which featured Clayton, Jackson, and Dilwyn Porter, critically examined the mythology of some of football’s greatest characters, in relation to the archival material which actually exists regarding them. Referees, it seems, took great pains to present themselves in a heroic light against agents of chaos: Porter’s examination of 1930s referee Percy Harper stated that that Harper featured death threats from supporters in his own personal archive, perhaps as kinds of trophies. The ‘World Cup’ panel featured its own fair share of surprises. Though Peter Alegi could not make it to discuss his history of South Africa 2010 (the perils of transatlantic travel!), Marion Stell and Daniel Malanski examined FIFA’s global showcase in relation to Australian and Brazilian football history respectively, showing us that domestic politics inevitably colors how individual nations view participation in the tournament.

One wonders what Football 200 will look like. Will the ‘beautiful game’ continue to stress the paradoxes of being the world’s most popular sport, while at the same time being a focal point for fierce tribalism? Will we be bemoaning the “good old days” of the 2010s, a day before money, political correctness, and middle-class sanitisation took their toll on the viewing experience of the people? The thread of nostalgia has always run through popular perceptions of what the game should be; and, as Football 150 and its constituent presentations have shown, there is no one unified consensus on what the game has represented, or what it continues to demonstrate regarding our world. It is as confused as we are; and perhaps that, above all, is the appropriate message of the conference.

**

Dr. Matthew L. McDowell is a lecturer in sport and recreation management at the University of Edinburgh, Moray House School of Education. He was written on the early history of Scottish association football, and is currently researching Scotland’s history with the Empire and Commonwealth Games competitions, and early North Atlantic footballing cultural encounters. Follow him on Twitter: @MattLMcDowell

By Bruce Berglund (cross-posted from @NewBookSports)

By Bruce Berglund (cross-posted from @NewBookSports)

In 2010, for the first time, an African nation hosted the FIFA World Cup. The advertisements surrounding the tournament used graphics and sounds intended to conjure the image of a vibrant, exotic land. In fact, though, the African-ness of the South African World Cup was pretty thin, when not wholly fabricated. For example, the music that introduced ESPN’s World Cup coverage sounded very African, as it opened with the sounding of an ox horn (the promo showed a bare-chested tribesman blowing the horn atop a mountain, silhouetted against the setting sun) and then built with pulsing drums and a choir singing layered refrains. But the piece had been written by a composer from Utah, the musicians had recorded it in Utah, and the choir consisted of members of the Broadway cast of The Lion King. At least Shakira’s ubiquitous song “Waka Waka (This Time for Africa)” had a more substantial African connection. It had been lifted, initially without credit, from a Cameroonian military song made popular in the 1980s by the group Golden Sounds.

The ironies of the 2010 tournament in South Africa are revealed in a number of essays in Africa’s World Cup: Critical Reflections on Play, Patriotism, Spectatorship, and Space (University of Michigan Press, 2013), edited by Peter Alegi and Chris Bolsmann. In the interview with Peter, we learn of the findings and observations of the volume’s contributors: an international collection of anthropologists, architectural critics, bloggers, geographers, sociologists, journalists, photographers, and former players who all attended matches in South Africa. They make sharp criticisms of class divides at the venues, the nationalism and commercialism, and, of course, the imperial reach of FIFA. But as we hear from Peter, the book’s authors were also fans. When mixing with other fans outside the stadiums, and then cheering their teams when the matches began, even normally skeptical academics and journalists were caught up in the event. Their experiences show that, for all its faults, the FIFA World Cup is still an incomparable event.

Click here to download the mp3 of the interview.

150 years after Ebenezer Morley and alumni of several elite schools founded the Football Association at the Freemasons’ Tavern in Great Queen Street, London, the Football 150 academic conference celebrates this historic anniversary. The gathering of soccerati takes place on 2-4 September at the National Football Museum in Manchester, UK. It is a joint project of the NFM, International Football Institute (University of Central Lancashire), and International Centre for Sports History and Culture (De Montfort University). The conference’s stated aims are “to reflect on the history of the Football Association and develop a blueprint for the future of the game and its study.”

Keynote speakers include historians Tony Mason, author David Goldblatt, and UEFA Executive Committee member Karen Espelund. A rich program features panels on the game’s global history, art, fan cultures and identities, migration, governance, media, and its broader social, political, and economic implications. The Arab Football Forum 2013 on Wednesday, September 4, will grapple with the potential impact of Qatar 2022 on MENA countries, the political role of football in the wake of the Arab spring, and women’s football.

My paper is part of a larger ongoing project on the history of South Africa’s hosting of the 2010 World Cup. Drawing from my digital archive of thousands of news items about the World Cup accumulated over nearly a decade, as well as government documents, published reports, oral testimony, personal observations, as well as the scholarly literature, the study argues that SA2010 reveals a paradox. On the one hand, South Africa’s image and influence in global football reached unprecedented heights thanks to the successful hosting of the tournament. But on the other hand, the overall social health of the local game (excepting a handful of elite clubs) suffered, particularly at the amateur, school, and youth level. In a small way, this paper addresses the lack of academic histories of World Cup tournaments and aims to generate discussion about the complex political, economic and cultural dynamics of football, particularly as they relate to South Africa, Africa, and more broadly to the Global South. (For more details on the topic, see my new co-edited book, with Chris Bolsmann, Africa’s World Cup.)

On my way to Manchester, it seems fitting to meet David Kilpatrick at the Freemasons Arms in London, “the spiritual home of the FA.” After a suitably English dining experience (whatever that means and entails), we’ll make our pilgrimage to the Emirates Stadium for my first North London derby!

Track conference proceedings via Twitter with the #Football150 hashtag and follow these participants: @DrDKilpatrick @ChrisBolsmann @SoccerHistoryUS @JeanMWilliams @FromaLeftWing @Davidsgoldblatt @MattLMcDowell @collinstony @mideastsoccer @j_richo1990 @GaryJamesWriter @StaceyPope20 @ShelleyBBC @ffion_ @mateobrown @DavidChilds @futbolprof

Online Fútbol University

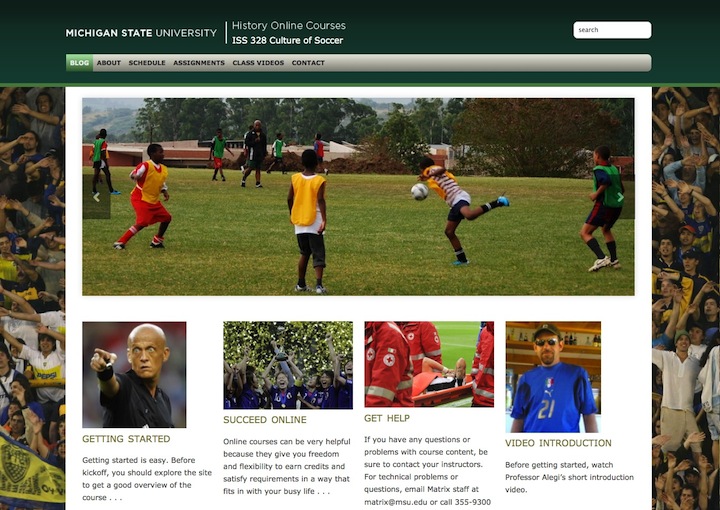

My online course “Culture of Soccer” launched today at Michigan State University. With 120 students enrolled, it recognizes and nurtures younger Americans’ growing appetite for fútbol. It may even be read as a “‘rejection’ of U.S. isolationist/exceptionalist attitudes,” as @OhioGooner put it to me on Twitter. But it’s also important to note that the course satisfies a social science component of MSU’s general education requirements.

As an exercise in pragmatism and poetry, this seven-week course explores fútbol and social change in a global context. It combines general analysis with specific case studies to make connections across time and space. By examining the intersections of the historical and the contemporary, the individual and the social, the local and the international, it explores how and why race, ethnicity, class, gender, media, and business made, and continue to make, the world of soccer we see today.

The course takes place almost entirely on the class WordPress site. Hosted and designed by the good people at Matrix–the digital humanities center at MSU–the class blog is where students write and comment on the assigned readings and the password-protected lecture videos. MSU’s new course management system (Desire2Learn) complements the WordPress site as a simple way to submit final papers and to release grades.

Why online teaching? First, it provides our department with much-needed funds for faculty research and the graduate program at a time of vicious budgetary cuts. Second, it strengthens our department’s partnership with Matrix. Third, online teaching funds two of my PhD students, Hikabwa Chipande and Liz Timbs, whose labor as teaching assistants greatly eases the burden of grading and class management. Last and certainly not least, the digital domain gives me another way to enjoy doing the work I love, and produce and share knowledge beyond the boundary of the brick-and-mortar classroom. Let the games begin.