Photo: Durban & District African FA select team, Rhodes Centenary tournament, Salisbury, Rhodesia (1953)

Football is Coming Home is pleased to receive and publish a guest essay by Zipho Dlangalala, a South African fútbologist who has coached players and trained coaches for many years at all levels. He is a teacher by profession. It has been lightly edited for style.

Guest Post by Zipho Dlangalala (makhandaz@hotmail.com)

KWAZULU-NATAL—All sports are played in, and influenced by, past and present social conditions. This is largely, if not entirely, because sport is played by people who are social beings.

When we see most of our South African players playing the same way, looking like identical midfielders, we should know instantly that we are looking at them with “foreign eyes.” They will always look like that as long as we evaluate them with foreign tools and criteria.

To African eyes, it is those midfield players that should reveal the nature and inclination of our players. Their creativity and desire to care for the ball—the uninhibited attraction to artistic modes of play—are great assets that we should have treasured so that their game exhibits the same attributes found in them naturally, at least before being diluted.

Regrettably, the Apartheid philosophy and its legacy was too strong for most of us. Based on seeing life through Master-Slave, Boss-Subordinate, Superior-Inferior, Rich-Poor, Educated-Illiterate, Advanced-Primitive, civilized-uncivilized relationships, this “baaskap” paradigm has engulfed us. Even when we know it is not desirable, we often find ourselves promoting it, advocating on its behalf through actions more than words.

It makes us feel acceptable and progressive to be seen as “the master.” We do everything and anything to feel accepted and to get approval from those who represent “the master” perspective. It has been engraved in us to look for this approval, otherwise we feel we do not have the capacity to stand by ourselves and achieve success on our own. The desire to be associated with, to be affiliated to, approved by, “the master” is hard to resist for most. It is this prevailing mentality in South Africa that undermined indigenous cultures, languages, restricted people’s movement and freedom to associate, to think, to explore, to design, to invent, to discover.

It is a “total control” approach of life. It attempts to control what people think and learn. Given the slightest opportunity, it dictates LIFE to each and every person who is supposed to be subordinated (and limited) to its wishes and desires.

In a cultural and socio-economic environment shaped by a social hierarchy long based on race, fertile ground exists for past tendencies to endure. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Football under these conditions cannot be sustained, let alone developed.

Looking at football through a particular lens inevitably results in the game looking in a particular manner. Are we using proper African perspectives to look at the game as it is in Africa? Are our views coloured to give us a special feeling? Are we ready to bring something new to world football or are we content to follow established paths and continue to consume what is already in the market? We are entrepreneurs and have skills. We need to develop them and show our own ideas to the world. We need to create something new in our football for the world to sit up and take note.

Category: Hosting

On Tuesday, June 2, Sepp Blatter announced his intention to resign as FIFA president just four days after winning reelection to a fifth term — an electoral victory that simply could not have happened without the support of FIFA’s African members.

According to unofficial calculations, the 133 votes secretly cast for Blatter came from Africa (53), Asia (46), and North America (minus the United States) and the Caribbean (34).

Why did Africans unanimously support the leader of a troubled, even loathed, organization which two days earlier witnessed the arrest of seven of its executives in Zurich on US bribery and corruption charges?

As an academic who has been researching, publishing and teaching the history and culture of African football for two decades, I want to offer a possible answer to this challenging question.

Read full text here at The Conversation.

The 2015 African Nations Cup begins on January 17 in Equatorial Guinea. The oil-rich dictatorship, a former Spanish colony with a population of 736,000, agreed to host the tournament on short notice after Morocco pulled out due to fears related to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

Africa’s most important tournament is organized by the Confederation of African Football (CAF), a trailblazing pan-Africanist institution born at the dawn of the era of decolonization. Joining the world body, as I’ve written elsewhere, was an honorable, quick, and inexpensive way for newly independent nations to assert their full membership in the international community.

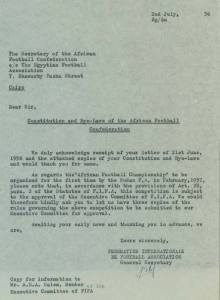

CAF took tangible shape at the 1956 FIFA Congress in Lisbon. There, delegates from Egypt, Sudan, and South Africa convened to draft a constitution and by-laws. The men also decided to organize a continental championship. Ethiopia was also involved in the discussions, but Yidnecatchew Tessema was unable to travel to Lisbon. The African proposal was later sent to FIFA for review and approval (see image at left).

On February 8, 1957, football officials from Sudan, Egypt, Ethiopia, and South Africa convened at Khartoum’s Grand Hotel to formally launch CAF. Fred Fell, a white man representing apartheid South Africa, was invited because his country was a member of FIFA and the Africans did not wish to be perceived as undiplomatic. In the meantime, the white South African football association gingerly debated the composition of the national team. However, the authorities Pretoria opposed a mixed selection and the white football establishment did not challenge the policy.

There are conflicting accounts about what happened next. CAF officials stated that they promptly excluded South Africa in a show of unequivocal pan-African solidarity. Fell and white South African football put forward a different story: they claimed they withdrew the team prior to any sanctions due to the team’s impending tour to Europe as well as security concerns linked to the ongoing Suez Crisis. Unfortunately, the minutes of the meeting at CAF were later destroyed in a fire so we may never know the exact truth of the matter. What is certain is that the South African issue did not disappear. To the contrary, the struggle against apartheid in football would become a powerful bond that united CAF and nearly all African nations for three decades.

South Africa’s absence in 1957 meant that only three teams, comprised of amateurs, participated in the inaugural African Nations Cup. Ethiopia, which had been drawn to play against South Africa, received a bye into the final. Egypt defeated hosts Sudan 2–1 and then dispatched Ethiopia 4–0 in the final watched by a crowd of 30,000 at the Stade Municipal. All four goals were scored by striker Mohammed Diab El-Attar “Ad Diba.” “Those were unforgettable matches,” Ad Diba recalled in an interview in 2001. “The success of this championship and its popularity amongst the Sudanese encouraged the African federation to organize a tournament on a biennial basis and to be played in a different country each time,” he said. Ad Diba made history again eleven years later in Addis Ababa, when he refereed the Afcon final between Congo (DRC) and Ghana (see video).

In those early days, CAF brought to life Kwame Nkrumah’s dream of a United States of Africa. At the same time, football provided a rare form of national culture, unity, and pride in postcolonial Africa.

Today, the African Nations Cup has transformed itself into a globalized commercial event with multinational corporate sponsors, matches on satellite television and online, many European coaches, and most players on the sixteen squads employed by European clubs. It is a far cry from 1957. And yet an alluring contradiction has endured: the Afcon showcases Pan-African solidarity while triggering 90-minute nationalism.

The Confederation of African Football has announced that Equatorial Guinea will replace Morocco as host nation for the 2015 African Nations Cup, the continent’s oldest and most prestigious international tournament.

The decision followed “fraternal and fruitful discussions” between CAF and Equatorial Guinea’s President Obiang, according to CAF’s official statement. Matches will be played in Malabo, Bata, Mongomo and Ebebiyin. The draw is scheduled for December 3 in Malabo.

The oil-rich former Spanish colony, population 736,000, previously co-hosted the tournament, with Gabon, in 2012.

CAF’s announcement brought a controversial and increasingly tense saga to a close. Morocco’s decision to back out of its commitment to stage the Nations Cup came in the wake of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. The North African nation’s withdrawal drew passionate criticism from many fans and observers in Africa and overseas.

Writing for The Guardian’s Comment is Free, Sean Jacobs (the South African founder of the Africa Is A Country website) argues that “a mix of politics, opportunism and self-interest seem to be behind Morocco’s decision.”

The incident, Jacobs explains, is evidence of Morocco’s “difficult relationship with nations south of the Sahara. African migrants, some on their way to Europe, regularly complain about harassment, violence and xenophobia.”

James Dorsey’s The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer blog took a similar tack. “Morocco can’t escape the impression that its decision was informed by prejudice,” especially within the context of a long and complex history of economic, cultural, and political relations between North African countries and sub-Saharan African nations. And, of course, fear shaped the decision as well. Fear, specifically, “about the possible impact of an Ebola case on tourism that accounts for an estimated ten percent of Morocco’s gross domestic product.”

Morocco’s seemingly contradictory decision not to host the Nations Cup in January but to go ahead and stage the FIFA World Club Cup next month sparked more criticism.

In the end, Africa’s grandest football show will go on thanks to Issa Hayatou, CAF’s president for the past 26 years, and President Obiang, Africa’s longest serving autocrat–in power since 1979 and at the head of the ruling Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea that holds 153 of 155 parliamentary seats.

This last-minute African Nations Cup resolution reminds me of FIFA General Secretary Jerome Valcke’s statement during the massive 2013 Confederations Cup protests in Brazil: “less democracy is sometimes better for organizing a World Cup.” And, in this case, it seems to work for an African Nations Cup too.

Quinton Fortune played seven seasons with Manchester United and 46 times for South Africa. On September 23, he wrote an excellent piece in The Guardian about a topic dear to me and to many readers of this blog: the impact of the 2010 World Cup on the growth and development of South African football.

Given the billions of rands spent on new and revamped stadiums and transport infrastructure, Fortune asks, was hosting the tournament a boon for the local game? “Judging by the poor attendances at top-flight games not involving the country’s two most popular clubs, Kaizer Chiefs and Orlando Pirates, who are also by far the most powerful in financial terms, and the poor performances of the national team Bafana Bafana, the answer unfortunately has to be a resounding ‘no’,” Fortune writes.

His concerns are numerous, important, and inter-related. The World Cup, Fortune asserts, did nothing to alter the Chiefs-Pirates duopoly, which continues to capture the lion’s share of the attention from fans, media, and sponsorship money. He points out that the quality of play in the Premier Soccer League is not terribly good, as evidenced by last year’s top scorer, Bernard Parker, boasting a meager 10 goals.

Fortune then notes how the swanky World Cup stadiums in Cape Town, Nelspruit, Polokwane, and Port Elizabeth are now massive financial drains on local municipalities struggling to deal with many pressing social needs in perhaps the most unequal country in the world.

The former Man United midfielder does not spare the PSL’s satellite broadcaster, SuperSport, which bankrolls the South African league while offering 24/7 matches and highlights of European football (such as EPL, La Liga, Serie A, Champions League). This contradiction is another reason why the PSL is “losing fans who prefer to watch the football from the comfort of their homes, receiving high definition pictures, while also having a choice of watching (better quality) football from other parts of the world,” says Fortune.

The way forward, Fortune concludes, requires harnessing South Africa’s world-class infrastructure and abundance of football talent to forge “a well-planned development programme which will develop that talent into realising its full potential.” How this should be done is the challenging part.

Scottish Independence, Britain, and FIFA

With the Scottish independence referendum a week away, Stefan Szymanski of the University of Michigan is thinking about what the outcome might mean for football.

Writing on the Soccernomics blog, he reminds us that the UK is the only nation-state with four members in FIFA and points to a historically tense relationship between the world body and the founders of the modern game.

According to Szymanski, “a vote for independence would change things.” FIFA might gain control of IFAB (responsible for the rules of the game); Welsh nationalism could receive a boost; and perhaps other football nations would call more loudly for the UK to field a single team, as it does in the Olympics.

Meanwhile in Scotland, the New York Times reports that “the country’s stadiums have become key battlegrounds for the yes and no campaigns.”

I chatted about the 2014 World Cup with Assumpta Oturu on KPFK Pacifica Radio‘s Spotlight Africa program.

We analyzed Brazil’s historic collapse, Germany’s youth development policies, club versus country loyalties, African teams’ performances and what can be done to improve their results in global football.

Listen to the entire July 19, 2014, show here.