Guest Post by *Liz Timbs

In August 2013, I had the privilege of spending three days with the Izichwe Football Club in Pietermaritzburg, capital of South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province. During my brief stay, I observed training sessions, visited players’ high schools, and interviewed some of the young men and coaches. The quotes below come from these conversations.

Every weekday afternoon at the University of KwaZulu-Natal campus in Pietermaritzburg, two dozen 10th grade-boys come together on a humble football pitch to hone their skills at Izichwe Football Club. Established in 2010 and named after the first military regiment (ibutho) commanded by Shaka Zulu, the club is “not just about kicking a ball,” says Thabo Dladla, founding director of Izichwe and Director of Soccer at UKZN. It is also about developing young men of character and respect who represent their communities and themselves with pride and honor.

Respect (inhlonipho in the Zulu language) and discipline (inkuliso) are core values at Izichwe as they are in Zulu culture more broadly. The coaches refer to the teenagers as amadoda (umarried young men) and even baba (father) to stress the importance of carrying themselves in a mature way on and off the pitch.

These two dozen high school boys at Izichwe embody the values and lessons imparted to them by their coaches, especially Thabo’s emphasis on showing self-respect as much as respect for others. When I spoke with the youngsters, they politely thanked me for coming to Pietermaritzburg to meet them and spoke with poise beyond their years.

“The program is not only about sports or soccer. It’s mostly about life,” Asanda tells me. Izichwe is “about respecting the people you are around, and playing fair, which applies in life. You do it the right way. Don’t cheat. Don’t cheat yourself.” Similarly, Simphiwe stated, without hesitation, that Izichwe had taught him “to work hard in life and to respect your instructors.” Asanda and Simphiwe’s statements were echoed in a team meeting I observed. Technical director Mhlanga Madondo, a police officer, entreated the players to look at their performances in the previous weekend’s tournament, stating that he expected them to “take responsibility for their own growth.”

“The program is not only about sports or soccer. It’s mostly about life,” Asanda tells me. Izichwe is “about respecting the people you are around, and playing fair, which applies in life. You do it the right way. Don’t cheat. Don’t cheat yourself.” Similarly, Simphiwe stated, without hesitation, that Izichwe had taught him “to work hard in life and to respect your instructors.” Asanda and Simphiwe’s statements were echoed in a team meeting I observed. Technical director Mhlanga Madondo, a police officer, entreated the players to look at their performances in the previous weekend’s tournament, stating that he expected them to “take responsibility for their own growth.”

Hard work is another crucial component of the Izichwe way. When I asked Lindi what the program had given him, he said, simply: “discipline.” Every day, without exception, the boys make their way to the university sports fields to train from 3:30p.m. to 5:30p.m. Many of the boys also play for their school teams at least one day a week (with one boy competing in cross country events in addition to playing school soccer). Saturday is match day in a local amateur league. Sundays are reserved for tournaments. This intense, demanding schedule instills in the boys not only physical endurance and strength, but mental acuity as well. Dladla believes this constant pressure shows the dedication and perseverance of his players. “Boys like Siphesehle (the cross country runner), he’s very, very competitive, you know? He did cross country; he came [to training], and I said, “Hey! You rest!” He said, “No, coach! I came to train!”

Although the players’ development as athletes is central to the program, Thabo, a former teacher and ex-professional footballer, regularly reminds players that “nothing in this life is as important as knowledge.” As a result, the program integrates numerous educational programs into their activities. Every night at the conclusion of practice, around 5:30, a group of the players gathers in a classroom on campus to study under the supervision of volunteer university students.

Although the players’ development as athletes is central to the program, Thabo, a former teacher and ex-professional footballer, regularly reminds players that “nothing in this life is as important as knowledge.” As a result, the program integrates numerous educational programs into their activities. Every night at the conclusion of practice, around 5:30, a group of the players gathers in a classroom on campus to study under the supervision of volunteer university students.

The coaches closely monitor individuals’ academic performance by reviewing school progress reports. This scrutiny, one parent explained, helps to “notice any hiccups in their progress at school.” In the opinion of Devon, the life sciences teacher at Alexandra High School, which several Izichwe boys attend, such devoted attention to player’s academics is unusual when compared with many other students who lack such careful supervision. “It’s a structured lifestyle which, I think, is lacking in a lot of our schools,” Devon explained. “I think that’s partly why these boys are so successful. They grow and they excel in every area.”

The youngsters openly expressed their gratitude to the adults who put precious time, energy, and resources into the program. “There are many kids out there who want this opportunity and we are very special to get that,” Mpumelelo said. Sandile stated unequivocally that the program has “changed the most part of my life.” Keelyn agreed, and without hesitation added that thanks to Izichwe, “I found myself.” Sandile spoke passionately about his appreciation for Izichwe: “Basically, what this program means to me is that it gives me the opportunity to realize a dream that I never thought . . . it was never something I believed I’d be able to do . . . it just made me realize, if I continue working hard enough, I can be one of the best players in the world.”

The youngsters openly expressed their gratitude to the adults who put precious time, energy, and resources into the program. “There are many kids out there who want this opportunity and we are very special to get that,” Mpumelelo said. Sandile stated unequivocally that the program has “changed the most part of my life.” Keelyn agreed, and without hesitation added that thanks to Izichwe, “I found myself.” Sandile spoke passionately about his appreciation for Izichwe: “Basically, what this program means to me is that it gives me the opportunity to realize a dream that I never thought . . . it was never something I believed I’d be able to do . . . it just made me realize, if I continue working hard enough, I can be one of the best players in the world.”

The Izichwe coaches are also grateful to be part of this project. Coach Madondo said that working with these young men has inspired him; he’s seen them “not just growing physically, but also [in] how to approach life.” Coach Ronnie “Reese” Chetty, who had a long coaching career including experiences in the United States, told me he is reinvigorated by the hard work and dedication these young men exhibit on a daily basis. The coaches are also driven and guided by the hardships, struggles, and perseverance of some of the players and families.

“It’s people like Sipesehle and Mhlengi’s mothers who sometimes give me lots of motivation when I see how hard they try, you know?” explained Thabo Dladla. “So then, I say: ‘Hey man! I cannot give up. I cannot let them down. So let me try and help them develop real men,’ you know?”

And from what I saw these Izichwe boys are becoming real men of immense diligence, humility, discipline, and respect. And, perhaps even more so, this community of boys, men, and parents demonstrates the great potential for grassroots soccer programs to fuel the development of not only athletic talent with a bright future in sport, but also of productive citizens in a democratic society.

—

*Liz Timbs is a PhD student in African history at Michigan State University. Her research interests are in the history of health and healing in South Africa; the professionalization of medicine; masculinity studies; and comparative studies between South Africa and the United States. Follow her on Twitter: @tizlimbs

Category: Hosting

By Bruce Berglund (cross-posted from @NewBookSports)

By Bruce Berglund (cross-posted from @NewBookSports)

In 2010, for the first time, an African nation hosted the FIFA World Cup. The advertisements surrounding the tournament used graphics and sounds intended to conjure the image of a vibrant, exotic land. In fact, though, the African-ness of the South African World Cup was pretty thin, when not wholly fabricated. For example, the music that introduced ESPN’s World Cup coverage sounded very African, as it opened with the sounding of an ox horn (the promo showed a bare-chested tribesman blowing the horn atop a mountain, silhouetted against the setting sun) and then built with pulsing drums and a choir singing layered refrains. But the piece had been written by a composer from Utah, the musicians had recorded it in Utah, and the choir consisted of members of the Broadway cast of The Lion King. At least Shakira’s ubiquitous song “Waka Waka (This Time for Africa)” had a more substantial African connection. It had been lifted, initially without credit, from a Cameroonian military song made popular in the 1980s by the group Golden Sounds.

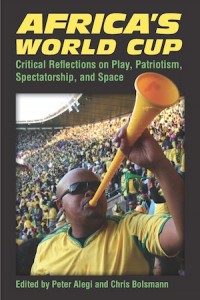

The ironies of the 2010 tournament in South Africa are revealed in a number of essays in Africa’s World Cup: Critical Reflections on Play, Patriotism, Spectatorship, and Space (University of Michigan Press, 2013), edited by Peter Alegi and Chris Bolsmann. In the interview with Peter, we learn of the findings and observations of the volume’s contributors: an international collection of anthropologists, architectural critics, bloggers, geographers, sociologists, journalists, photographers, and former players who all attended matches in South Africa. They make sharp criticisms of class divides at the venues, the nationalism and commercialism, and, of course, the imperial reach of FIFA. But as we hear from Peter, the book’s authors were also fans. When mixing with other fans outside the stadiums, and then cheering their teams when the matches began, even normally skeptical academics and journalists were caught up in the event. Their experiences show that, for all its faults, the FIFA World Cup is still an incomparable event.

Click here to download the mp3 of the interview.

After the World Cup is Gone

By Sean Jacobs (@Africasacountry)

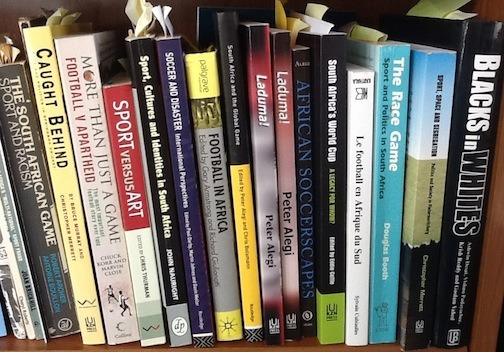

Do we need a book on the 2010 World Cup already? That’s the first question I asked Peter Alegi and Chris Bolsmann, editors of the brand new volume, Africa’s World Cup (University of Michigan Press, 2013). Their quick riposte: “Nobel Peace laureate Desmond Tutu said that ‘anyone who wasn’t thrilled by the World Cup needs to see their psychiatrist.’ Since therapists cost too much, we wrote a book instead.” That’s a good enough reason, and Peter and Chris are uniquely qualified to edit the book. Peter teaches history at Michigan State University and has written two books about African football (here and here). He also runs a football blog and shoots videos of himself walking from his home to his office playing keepy uppy. Chris, a former club footballer in South Africa’s capital Pretoria, is a sociologist based in the UK. He has written a number of academic articles about football, including on the cultural significance of Mark Fish, one of a few white players to represent South Africa after Apartheid and who played for Lazio in Serie A (he’s one of a few South Africans who played in Serie A). As far as we know, this–three years later–is the first substantive attempt, whether popular or from scholars to make sense of what marketers also dubbed “Africa’s World Cup.” The book is especially relevant now given recent events in Brazil. What follows is a transcript of an email interview we did a few weeks back.

Is your book the first of its genre?

Africa’s World Cup is a valuable source for thinking more deeply about the matches, fan cultures, media coverage, cultural exhibits, and political and economic struggles related to the tournament. We, the editors, came to this project on the strength of fifteen years publishing scholarly books and journal articles on the history and sociology of South African and African football. We teach university courses about the subject and actively participate in the Football Scholars Forum (full disclosure: Sean is a member), an online fútbol think tank. Besides this professional expertise, we both share a lifelong passion for the game. We have played in ramshackle township grounds in South Africa, coached at the youth level, and attended countless matches across the country, from Athlone and Atteridgeville to Pietermaritzburg and Soweto. The World Cup coming to South Africa was hugely meaningful to both of us. It inspired us to bring together an international team of academics, journalists, writers, bloggers, players, coaches, museum curators, photographers, and architects to reflect on the experience and its aftermath.

Another distinctive quality of this book is its cross-over nature. It combines essayistic writing with scholarly analysis. Written in the first person, the two-dozen chapters are concise pieces that can be read in just about any order. This format and style should appeal to general readers and specialists alike. We like to think of it as a book that works well for university courses on Africa, sport, and globalization and also makes for good bedside reading. Africa’s World Cup is neither the first nor probably the last book of its kind. But it is the only book that does what it does.

The publicity suggest the book “reflect(s) on the … broader significance, meanings, complexities, and contradictions” of the 2010 World Cup? Can you say more about that?

The book is divided into four parts, arranged thematically. The essays in Part 1 consider the ways in which the 2010 World Cup refashioned urban spaces in host cities and the local struggles these changes engendered. Chapters on Cape Town, Johannesburg, and Durban by Daniel Herwitz, Marc Fletcher, David Roberts and Orli Bass. Killian Doherty note how and why the tournament accentuated processes of inclusion and exclusion in South African society. Airports were built or renovated; central business districts got facelifts; public transport improved; and broadband access widened. But it was mostly those of us who could afford to pay for expensive tickets that gained access to stadiums and FIFA “exclusion zones.” Many essays in the book point to this gentrification of the “people’s game” as evidence that while some racial mixing is taking place in contemporary South Africa, it is happening mainly in privatized and closely policed bourgeois spaces.

Part 2 shifts to how football, the World Cup, and South Africa were represented in popular art, music, media, and visual culture both locally and abroad. Jennifer Doyle’s essay juxtaposes Shakira’s plagiarism of the official World Cup song and Coca-Cola’s selective editing of K’naan’s song “Wavin’ Flag” with the Internet distribution of oppositional World Cup music. Solomon Waliaula explores the paradox of the vuvuzela—possibly the most enduring symbol of the tournament—as both leisure and noise. His essay makes some really interesting connections between centuries-old rites of passage in east Africa and today’s rituals of spectatorship in South Africa. Fiona Rankin-Smith looks at the aesthetics and visuals of football-related art in the Halakasha! exhibition she curated at a Johannesburg gallery during the World Cup. Finally, John Harpham records the sounds and conversations among patrons watching France’s World Cup matches at a café in Paris and, in the process, uses soccer to explore belonging and identity in contemporary France.

Part 3, the longest in the book, focuses on the complicated relationships between soccer and patriotism, nationalism, and pan-Africanism. The eight essays in this section chronicle the experiences of supporters of South Africa, Ghana, England, Uruguay, United States, Netherlands, and Mexico. These fans’ reflections provide a glimpse into processes of self-identification and allegiance and into the multiple meanings of the tournament. Individually and collectively, these essays do a terrific job of humanizing the World Cup corporate spectacle. A few examples: Chris Bolsmann writes about his dilemma on whether to sing the “Die Stem” portion of the South African national anthem due to its association with Afrikaner nationalism and apartheid. Traveling after the USA-England match, Andrew Guest is so revolted by the ignorance and jingoism of a fellow American supporter that when the latter tried to shake his hand at the end of the journey the author just turned and walked away. David Patrick Lane reveals the secret behind Uruguay’s surprising run to the semifinals. Apparently, it owed as much to Oscar Tabarez’s scientific coaching method and choosing Kimberley as a tranquilo base camp, as it did to the team’s devotion to candombe beats and garra Charrúa (Charruan claws, or fighting spirit). These are just some tasty morsels of what you can dig into in this part of the book.

Part 4 looks at the political discourses and economic rationales of World Cup hosting. Albert Grundlingh and John Nauright, well-known historians of South African sport, compare the broader impact of the 1995 Rugby World Cup and the 2010 soccer World Cup. Their main point is that neither event did much to address poverty, unemployment, or other critical socioeconomic questions facing postapartheid South Africa. Laurent Dubois acknowledges such limitations but encourages us to appreciate that the World Cup is the planet’s largest theater, an escapist narrative that plays out on iconic stages, with unpredictable outcomes, plot twists and turns, and unusual characters in the stands and on the pitch. Meg Vandermerwe questions World Cup discourse about pan-African solidarity in light of the xenophobic tensions in South Africa.

The book closes with a World Cup roundtable. As a South African, the World Cup made me very proud,” says Rodney Reiners, a former professional player and now head soccer writer at the Cape Argus. “Considering where this country has come from—once a pariah of the world, then the miracle of democratic change, and the enduring negativity of Afro-pessimism—we showed that “Africa can do world class.” According to Thabo Dladla, founder of the Izichwe Youth Football program in KwaZulu-Natal, there were also missed opportunities. “I had expected that long before the World Cup kicked off, concerted investments in terms of providing the facilities, providing equipment, providing the coaches for the kids would have occurred all over South Africa,” Dladla states. “This grassroots development would have been the biggest legacy of the World Cup. But we did not do that . . . The World Cup was successful, but too many young people in this country still have no hope, they have no future.”

What is the significance of the 2010 World Cup apart from the fact that it was the first World Cup played on African soil?

There are positive and negative aspects to the World Cup’s significance. On the positive side, most South Africans were quite pleased with the ways in which FIFA and global media congratulated South Africa for staging a world-class event. There was just about universal praise for South Africa’s warm hospitality, high modernist stadiums, tight security, sound event management, adequate accommodation, good transportation, and functional telecommunication networks. The World Cup added luster to “Brand South Africa” and fostered genuine patriotic unity for a short while. As Dladla puts it in the roundtable: “Maybe we need to have a World Cup every day in this country!”

On the negative side, the tournament highlighted the inequitable nature of FIFA’s hosting arrangement. The world body earned more than $3 billion in tax-free revenue, largely through the sale of television rights and corporate sponsorships, while South Africa spent more than twice that amount in public funds and made at most $100 million from ticket sales. World Cup economics privatized profits and socialized costs in other ways. South African shopping mall retailers, construction giants, and food and hospitality companies did well, but the overall impact on GDP in South Africa amounted to between 0.3 and 0.5 percent—roughly one-tenth of the original estimate. That most stadiums built or renovated for the World Cup now stand empty on most weekends is a sad and entirely predictable legacy. Even Local Organizing Committee CEO Danny Jordaan recognizes this fact: “Many of the expectations among South Africans were too high,” said Jordaan in a recent interview, referring to the viability of the marginal stadiums. “We did not think it through and engage all the stakeholders, large and small.” Finally, Parliament’s passed a special law (the 2010 FIFA World Cup Special Measures Acts 11 and 12 of 2006) which set a potentially dangerous precedent. These laws meant that for the duration of the tournament, South Africa surrendered its national sovereignty and suspended some constitutional rights in order to protect FIFA’s cash cow.

Whose legacy among football administrators was or were most advanced by the 2010 World Cup and why?

As a vocal advocate for South Africa’s World Cup, Sepp Blatter delivered on a campaign promise made to African FIFA delegates in the late 1990s: bringing the World Cup to Africa for the first time. 2010 cultivated a perception of Blatter as a “friend of Africa” which, among other things, he can use to deflect attention from FIFA bribery and corruption scandals. On the African side, the 2010 World Cup strengthened the position and status of Issa Hayatou, as we saw in his recent reelection as president of the Confederation of African Football (which he’s led since 1988). And then Irvin Khoza, Local Organizing Committee chair, probably solidified his grip on power in South African football and gained indispensable experience in managing a global megaevent.

If there’s a villain or villains in this piece, who gets to play that role(s)?

World Cup soccer is a complex phenomenon. The chapters in our book do not really identify heroes and villains. Rather than judge or assign blame, the essays draw on a rich set of sources and data, as well as personal experiences, to better understand the politics, economics, social, and sporting dimensions of the tournament. Having said that, some of the most important critiques raised in the book have to do with the nature and impact of financial and legal arrangements between FIFA and South Africa, as well as the development of public spaces and infrastructure in host cities for the benefit of foreign tourists and the local consumer class. World Cup sponsors and other corporate interests, local and international, are called to task for shaping fans’ experiences at South African stadiums and fan parks. The small number of black African fans and of African supporters from outside South Africa chipped away at the “Africanness” of the competition. Finally, the trend toward conservative, risk-averse football, Spain, Germany, and Mexico excepted, comes in for its fair share of criticism.

World Cups are intensely mediated and that’s how most people experienced them. Not just the live match, but the lead-up, the 24-hour banter, the news programs about construction of stadiums, etcetera. How would you characterize the coverage of the 2010 World Cup in global media, i.e. major Western media? Can you also comment on why do you think coverage swung from pre-tournament scare-mongering to post-tournament assessments like that of the International Herald Tribune: “South Africa’s triumph in being host to the World Cup can no longer be questioned”?

It was pretty amazing to see how in the end even conservative media in Britain and the United States went from skeptical or worse to triumphalist in their assessment of South Africa 2010. The day after the final the Times of London ran a story about how “The World Cup has been a triumph for South Africa.” The Wall Street Journal countered with its own version under the headline “Rejoice, the Beloved Country, toot your own vuvuzela.” The pendulum swung so wildly because the tournament went off with few glitches and, perhaps, because sports coverage tends to be emotional and even sensationalistic.

And in South African media? Did old South African divisions play out in the coverage?

While there is a reasonable diversity of opinions in South African media, government agendas and corporate interests decisively shaped media coverage of 2010. Between 2004 and 2008, there were occasions when the government was openly criticized, as seen in the debate over the construction of the Green Point Stadium in Cape Town. But by 2009, with the Confederations Cup approaching, private and public media turned actively boosterist. (Watch “Think Positive” ad by FNB.) It is also true that media coverage reflected South Africans’ passion for the game and genuine World Cup excitement. Even the Mail & Guardian weekly at times struggled to balance its “watchdog role” with riding the World Cup bandwagon.

After the final, self-congratulatory headlines and stories that filled South African television, radio, newspapers, and electronic media. South African big business enthusiastically joined the praise singers’ chorus, taking out full-page advertisements in the country’s major dailies: “Today this is the greatest country in the world,” declared First National Bank, an official World Cup sponsor; “South Africa: you can be proud,” stated the Pick ’n Pay supermarket chain. Within a few weeks of the World Cup’s conclusion, however, this united front faded away. Cricket and rugby returned to their dominant position in mainstream media while SABC failed to broadcast several Bafana Bafana matches.

Do we get a sense from the book how other Africans on the continent, outside South Africa, experienced the World Cup?

Simon Akindes, a former player on Benin’s national team, grapples with how his love for Arsenal and the absence of his motherland of Benin complicated which World Cup side he chose to support. Together with his U.S.-born son, Akindes eventually decided to cheer for teams emphasizing an attractive style of play over soulless efficiency. Dutch journalist Niels Posthumus and Austrian photographer Anna Mayumi Kerber embarked on an overland trip from Europe to South Africa in which they travelled through a number of African countries in the lead-up to the World Cup finals. In their description of the countries they visited we get a sense of what the World Cup meant to Africans outside of South Africa on the continent.

Football in South Africa is seen as a black sport which it is to a large extent (in the country’s media or at matches), despite a long and deep history of football among some white South Africans. Why is that so? Did the 2010 World Cup change that and, if so, in what ways?

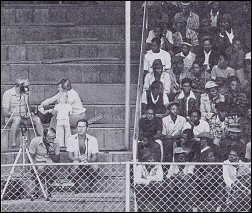

Since the end of World War Two, large crowds of black and white South Africans watched and enjoyed football in rival leagues. The amateur South African Soccer Federation in the 1950s and the semi-professional South African Soccer League in the 1960s were at the forefront of nonracial football in apartheid South Africa. But what is also interesting, and often overlooked, is that between the mid-1950s and mid-1970s football matched rugby as the most popular spectator sport among white South Africans. The National Party tinkered with the rougher edges of apartheid sport in the 1970s. First, the regime permitted tournaments where racially defined teams competed against each other in stadiums with segregated seating. Then, after Soweto ’76, racially mixed football was allowed at elite club level. As a result of these shifts, the whites-only National Football League collapsed, clubs fielded mixed teams, and segregation at stadiums ended. Many professional white teams returned to whites-only amateur football leagues, which were still shielded by apartheid laws. White fans deserted integrated football and increasingly turned their attention to rugby, which became professional in the early 1990s. The 1995 Rugby World Cup victory added to the passion and excitement many white South African developed for that sport. As several contributors to our book point out, the 2010 FIFA World Cup attracted significant numbers of white South Africans. The possibility of seeing world-class players and teams competing in newly built stadiums was an opportunity not to be missed. But in the long term, unfortunately, the World Cup did not change the racial divisions in South African football.

What for you were–or your contributors–the most defining moment off the pitch of the 2010 World Cup?

An interesting aspect of the book is how each contributor identifies a different defining moment. But many authors reflect on the experiences of walking in and around South African stadiums and city centers for the first time; using public transport to get to matches; and interacting openly with scores of international visitors and South Africans.

And on the pitch?

Siphiwe Tshabalala’s goal for South Africa against Mexico in the opening game at Soccer City represents a poignant moment for South Africans. For a dozen minutes it seemed like the “Madiba Magic” era of the mid-1990s had returned. Another extraordinary moment was Luis Suarez’s handball in the dying moments of extra time in the quarterfinal between Ghana and Uruguay. Suarez’s “save” and Asamoah Gyan’s subsequent penalty miss essentially prevented the Black Stars from becoming the first African side to reach a World Cup semifinal. (Ghana went on to lose the penalty shoot-out). The Final was no World Cup classic, but most observers seemed pleased that Spain’s “tiki-taka” style had overcome the physical brutality of the Dutch team to lift the trophy at Soccer City.

The World Cup was a marketer’s dream. Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Brand South Africa with its “Diski” ads, among others, latched onto the tournament. What do you think were the most striking campaigns of the tournament?

Within South Africa, a number of large corporations latched onto the success of the World Cup by placing full-page color advertisements in national newspapers at the end of the tournament. Banks and grocery chains were quick to congratulate South Africa on hosting a ‘World Class event’. The most successful campaign was “Football Friday.” It began as a corporate initiative by the Southern Sun hotel group, which encouraged its employees to wear football shirts on Fridays. It was later adopted by the Local Organizing Committee and government agencies and departments. This initiative generated huge enthusiasm for the World Cup around the country. Another striking marketing strategy was MTN’s “Ayoba” campaign. This neologism (loosely translated as “cool”) quickly entered into South Africans’ and foreigners’ World Cup lexicon.

The 2010 World Cup was billed as “Africa’s World Cup” by the local organizers and FIFA. How close to that description did the tournament come?

The World Cup was held in South Africa; six African teams competed; and thousands of Africans attended matches. The opening and closing ceremonies were symbolically laden with African images, new and old. However, the book demonstrates that the tournament was first and foremost a slickly run corporate operation overseen by FIFA, albeit with the vital assistance of the host nation’s government and the local organizing committee. In this respect, South Africa was part of a broader global trend that has seen nations from outside the West host global mega sporting events. Beijing staged the 2008 Summer Olympics and Delhi the 2010 Commonwealth Games. Brazil is hosting the 2014 World Cup as well as the 2016 Summer Games in Rio de Janeiro. Russia is due to host the 2014 Winter Games (in seaside Sochi!) and the 2018 World Cup. Placed in this wider context, the personal experiences and social analysis presented in this book should resonate beyond South Africa 2010.

One of the contributors Davy Lane writes about Uruguay’s World Cup experience. Can you give us a sense of how he deals with the Luis Suarez’s gamesmanship against Ghana and the reaction to it?

Davy Lane refers to the Uruguayan team as underdogs that “became the stray of the tournament, ugly, unloved, and unwanted.” When Suárez pulled off the most important “save” of the 2010 World Cup, Lane writes, he showed us something about sacrifice: he “epitomized selflessness, surrendering himself for his team.” In that dramatic game’s aftermath, Uruguay came in for much abuse, but this was not unanimous. As Lane reminds us, many took into account that Ghana squandered a golden opportunity to win the game through Gyan’s missed penalty.

South Africa recently hosted the 2013 African Cup of Nations. Could we detect any of 2010 legacies in the running of the tournament?

The 2013 African Nations Cup was an understated yet well-managed event. The South African government spent millions, rather than billions, on hosting the Nations Cup. Unlike 2010, one could have been in the country and not noticed that the continental showcase was even taking place. Most matches saw large sections of the stadiums empty despite relatively cheap tickets. The quality of the playing surface at Mbombela and Soccer City, renamed the National Stadium for the occasion, was abysmal. The Mbombela pitch looked like a sand pit, while parts of Soccer City’s barren pitch was spray painted green. On the plus side, local vendors were not severely restricted from trading in “FIFA exclusion zones,” but instead did fairly brisk business around the Nations Cup venues.

One final comment about the legacy of 2010 and South Africa’s enthusiastic hosting of international sporting events. In the book’s conclusion Mohlomi Maubane puts it this way: “the World Cup was dangled as a carrot to the poor, as a beacon of hope and the answer to their material hardships. Now that the tournament has come and gone, it is clear that millions of people still struggle to make ends meet. What is the ruling class now going to dangle? The 2020 bid for the Olympics in Durban?”

*This article is cross-posted between FICH and the popular Africa is A Country blog.

Guest Post by *Marc Fletcher

Gloomy skies and wet weather greeted the Research Forum on South African Football held at the University of Johannesburg (UJ) last month. The bleak conditions made for an intimate crowd, but the academics, journalists and sports practitioners in attendance were rewarded with three strikingly different presentations on varying aspects of the “beautiful game” in South Africa. The aim of the forum was to advance the specialized study of soccer in the country and beyond.

First up was Chris Bolsmann, a South African sociologist based at Aston University, Birmingham. His paper entitled “Professional Football in Apartheid South Africa: Leisure, Consumption and Identity in the National Football League, 1959-1977” provided a rich history of the whites-only National Football League (NFL) during apartheid. The common misconception of South African football is that it has historically been, and continues to be, an exclusively black, working-class game. Yet, Chris’s work challenges such a perception and begins to reconstruct a past that is often forgotten or even ignored. Matches in this white league were staged in front of segregated crowds. A successful corporate affair, the NFL attracted a host of world-renowned players, including George Best and Bobby Charlton. In concluding that the NFL became the leisure and sporting entertainment of choice for significant numbers of white and black (particularly Indian and Coloured) South Africans, this history emphasized how football in South Africa has had a more diverse support base than is often acknowledged.

First up was Chris Bolsmann, a South African sociologist based at Aston University, Birmingham. His paper entitled “Professional Football in Apartheid South Africa: Leisure, Consumption and Identity in the National Football League, 1959-1977” provided a rich history of the whites-only National Football League (NFL) during apartheid. The common misconception of South African football is that it has historically been, and continues to be, an exclusively black, working-class game. Yet, Chris’s work challenges such a perception and begins to reconstruct a past that is often forgotten or even ignored. Matches in this white league were staged in front of segregated crowds. A successful corporate affair, the NFL attracted a host of world-renowned players, including George Best and Bobby Charlton. In concluding that the NFL became the leisure and sporting entertainment of choice for significant numbers of white and black (particularly Indian and Coloured) South Africans, this history emphasized how football in South Africa has had a more diverse support base than is often acknowledged.

My paper on “Divisions, Difference and Encounters in Johannesburg Soccer Fandom,” explored contemporary cultures of fandom beset by race and class divisions, where domestic football is regularly constructed as an Africanized space without white supporters. However, through an ethnography of Kaizer Chiefs, Bidvest Wits, and Manchester United supporters’ clubs in Johannesburg, I began to explore the deeper complexities, where supporters on the margins of these groups began to engage with the other. In doing so, some fans challenged these social barriers in football and thus reinterpreted their understanding of soccer fandom and their wider experiences of everyday life in the city.

My paper on “Divisions, Difference and Encounters in Johannesburg Soccer Fandom,” explored contemporary cultures of fandom beset by race and class divisions, where domestic football is regularly constructed as an Africanized space without white supporters. However, through an ethnography of Kaizer Chiefs, Bidvest Wits, and Manchester United supporters’ clubs in Johannesburg, I began to explore the deeper complexities, where supporters on the margins of these groups began to engage with the other. In doing so, some fans challenged these social barriers in football and thus reinterpreted their understanding of soccer fandom and their wider experiences of everyday life in the city.

Chris Fortuin, based in the Department of Sport and Movement Studies at UJ, gave the third paper–an eye-opening account of the grim state of youth development in South African football. It was alarming to hear the inadequate ratio of qualified youth coaches to players in South Africa compared to some of the giants of international soccer, especially Spain. The shortage of such coaches, along with the absence of a coherent development plan at the national level, is harming the game at all levels and has contributed to the malaise of the men’s national team, Bafana Bafana.

Chris Fortuin, based in the Department of Sport and Movement Studies at UJ, gave the third paper–an eye-opening account of the grim state of youth development in South African football. It was alarming to hear the inadequate ratio of qualified youth coaches to players in South Africa compared to some of the giants of international soccer, especially Spain. The shortage of such coaches, along with the absence of a coherent development plan at the national level, is harming the game at all levels and has contributed to the malaise of the men’s national team, Bafana Bafana.

The presentations encouraged members of the audience to think more seriously about football as an academic field of inquiry. During the second half of the forum panelists responded to numerous questions from the floor. One question stuck out, one that is often asked; why are black South Africans not writing about this subject? It is true that much of what is written on the subject is by foreigners like me. But a main goal of football scholars, regardless of origin, is to empower South African students in the humanities and social sciences (and other fields) with tools and desire to critically engage with football studies.

With questions on the presentations filling up the second half, the question of where does the academic study of South African football go from here was left unresolved. Events such as the UJ forum can play a vital role in motivating South African scholars to research and write about their game. Clearly, football is a legitimate and fascinating area of research. But many more events like the forum are needed to further develop the field and chart future directions.

To this end, readers of this blog who are in the Johannesburg area, are welcome to attend the UJ Wednesday Seminar Series on Wednesday, May 8, at 3:30pm, where I will be presenting a paper entitled “Reinforcing Divisions and Blurring Boundaries: Race, Identity and the Contradictions of Johannesburg Soccer Fandom.” For details about the event click here.

The journey continues.

*Marc Fletcher, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Johannesburg, blogs at One Man and His Football: Tales of the Global Game. Follow him on Twitter: @MarcFletcher1

Police in riot gear battle protestors in the streets of Rio de Janeiro. Aggressive slum clearance threatens favelas. Gentrification at Maracanã Stadium. FIFA exclusion zones around World Cup venues. Sound familiar?

As readers of this blog know, South Africa staged a successful World Cup in 2010, marketing the country globally to tourists and foreign investors, and uniting, albeit temporarily, a nation divided along racial and economic fault lines. South Africa’s experience was part of a larger trend, that of BRICS countries enthusiastically embracing the global mega sporting events business: from Beijing (2008 Summer Olympics) and Delhi (2010 Commonwealth Games) to Brazil (2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics) and Russia (2014 Winter Games [Sochi] and 2018 World Cup).

Recent media coverage of Brazil’s preparations reveals growing FIFA unease with delays in infrastructure construction projects and other hosting problems. Speaking at a FIFA academic symposium last week, FIFA General Secretary Jerome Valcke expressed frustration with Brazil’s government, saying that “less democracy is sometimes better for organizing a World Cup,” according to a Reuters wire story. Valcke’s extraordinary remark confirmed some experts’ suspicions about FIFA’s underlying rationale for choosing autocratic Russia and Qatar (2022) as World Cup hosts.

Another story about 2014 World Cup stadiums was published in the New York Times Goal blog. James Young’s “White Elephant Hunting in Brazil” highlighted the importance of staging matches across the country. It concluded that while there were some troubling questions about the preparations, “Nevertheless, amid talk of delays and spiraling costs, the 2014 World Cup will at least be an event for all Brazil. In a country where the north-south cultural and economic divide is so deeply engrained, that at least is something to celebrate.”

Young’s article elicited a sharp response from Chris Gaffney (@geostadia), Visiting Professor at the Graduate School of Architecture and Urbanism at Rio’s Federal University, on his blog “Hunting White Elephants.”

“The projects associated with the World Cup were poorly planned, hastily executed (if at all) and may not serve the long-term needs of the cities or the country,” Gaffney writes. “There is no redress (as the [NYT] author suggests) of historically-situated cultural or economic divides in World Cup investment, especially when we take into consideration the astronomical sums being invested in Rio de Janeiro for the 2016 Olympics.” Gaffney concludes emphatically by pointing out that Young’s piece “does not attempt to kill White Elephants, but to make them into bichos de estimação (pets).”

On Saturday, April 27, ABC radio in Australia picked up on Gaffney’s critical blogging. Listen to Geraldine Doogue’s interview with him here.

Next month the University of Johannesburg is hosting an exciting “Research Forum on South African Football.” Organized by the UJ Department of Sport and Movement Studies, the gathering will consider three papers that address socio-historical, sociological, and developmental aspects of football in South Africa, as well as broader issues related to the local game.

In his paper “Professional Football in Apartheid South Africa: Leisure, Consumption and Identity in the National Football League, 1959-1977,” sociologist Chris Bolsmann (Aston University) will present a preliminary analysis of the NFL, a “whites-only” league established in 1959 by a group of (white) Johannesburg businessmen. Playing in segregated stadiums, the NFL introduced professional football to South Africa. At the height of its popularity, it had two divisions, attracted significant corporate sponsorship, and recruited prominent foreign players, such as George Best and Bobby Charlton. The NFL became the leisure and sporting entertainment of choice for significant numbers of black and white South Africans and was unparalleled in popularity during this period.

Ethnographer Marc Fletcher (Department of Sociology, University of Johannesburg) will explore contemporary dynamics in a paper titled “Divisions, Difference and Encounters in Johannesburg Soccer Fandom.” This ethnography of Kaizer Chiefs, Bidvest Wits, and Manchester United supporters’ clubs in the city shows how supporters on the margins of these groups began to engage with the other, crossed racial and class divisions, and thus reinterpreted their understanding of soccer fandom and their wider experiences of everyday life in the city.

Last but not least, Chris Fortuin (Department of Sport and Movement Studies, University of Johannesburg) will discuss “Youth Football Development in South Africa.” The paper notes how in South Africa there is a severe lack of focus on youth football development to sustain national junior and senior teams. I also highlights that youth football development is not coordinated, there is limited success in nurturing young players for the international market, and coach development with a specific focus on youth football is strongly lacking.

This forum takes place on April 19, 2013, 10:00-12:00 at the University of Johannesburg’s Protea Auditorium, School of Hospitality and Tourism, Bunting Road Campus, Auckland Park. For more details please contact Dr. Chris Bolsmann (chris [dot] bolsmann [AT] aston [dot] ac [dot] uk or @ChrisBolsmann on Twitter).

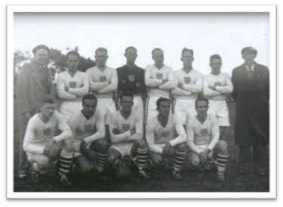

Rethinking American Soccer History

The Football Scholars Forum, an online fútbol think tank, met on February 26, 2013, for a lively session on the history of American soccer. Steven Apostolov shared a paper on Massachusetts; Gabe Logan on Chicago; and Tom McCabe on northern New Jersey. David Kilpatrick, official historian of the New York Cosmos, moderated the 90-minute conversation.

The Football Scholars Forum, an online fútbol think tank, met on February 26, 2013, for a lively session on the history of American soccer. Steven Apostolov shared a paper on Massachusetts; Gabe Logan on Chicago; and Tom McCabe on northern New Jersey. David Kilpatrick, official historian of the New York Cosmos, moderated the 90-minute conversation.

Listen to the audio from the session here.

Twitter timeline here.