Photo courtesy of Chris Bolsmann

The Big Boss Man of Nigeria’s Super Eagles, Stephen Keshi, transformed perennial underachievers of the African game into continental champions in the recent African Nations Cup in South Africa.

Keshi weeded out huge egos. He selected players based on ability, merit, and, most important, attitude. He imposed strict curfews on a team brimming with young players of limited experience drawn from Nigerian clubs rather than European ones. Thanks to his steady leadership, the Super Eagles defied the prognostications of pundits and fans alike in claiming their third African title.

Keshi knows how to win. He wore the captain’s armband in Nigeria’s previous Nations Cup triumph in 1994 against Zambia. The captain of the opposing side in that final in Tunis was Kalusha Bwalya, who played an important role in masterminding Chipolopolo’s 2012 championship run. “King Kalu,” currently Zambian Football Association president, saw to it that the nucleus of that winning Chipolopolo side stuck together for more than five years. Big Boss Keshi, on the other hand, overcame a perennial African problem by selecting a team based on what they can do, and what they are willing to do for the collective, instead of which European team they play for. In orchestrating their respective countries’ African triumphs, Bwalya and Keshi merely implemented a philosophy rarely found in most parts of African football: common sense.

The enduring lesson from Nigeria’s 2013 Nations Cup victory is that having so-called big names in your team is less than important than unity and a desire to win. As I have argued before, it is this generation of African football luminaries that must ensure that our football realizes its potential. When Keshi quit his job immediately after winning the title he cast light on the mediocrity of Nigerian football administration. (His resignation has since been withdrawn. Click here and here for more details.) The sight of South African Football Association president Kirsten Nemantandani looking bamboozled, insipid, and nervous when tasked with ceremoniously passing the CAF flag to Issa Hayatou is another reminder of why African football management should be the prerogative of competent, visionary people; not motley crews of myopic sorts whose organizations find themselves in the midst of FIFA match-fixing investigations.

Witnessing Slim Jedidi’s farcical refereeing in the Ghana-Burkina Faso semifinal, a fellow brother of mine noted: “Success in Africa is never rewarded because merit is hated. Why? Because the Big Men are there by fraud and manipulation.” Thank you to runners-up Burkina Faso and to Stephen Keshi for demonstrating how African football can soar above the deeds of those who always try to bring us backwards. May it continue in that trajectory.

Category: Hosting

Nigeria’s Triumph, Africa’s Tournament

Photos courtesy of Chris Bolsmann

By Chris Bolsmann (@ChrisBolsmann) and Marc Fletcher (@MarcFletcher1)

February 11, 2013 (23rd anniversary of Mandela’s release from prison.)

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA

Chris Bolsmann (CB): In February 1996, I celebrated with 100,000 other delirious South Africans packed into Soccer City after we beat Tunisia in the African Nations Cup final. It was a special victory and an important moment in South African sports history. It was more special that the 1995 rugby World Cup win because the soccer crown was won by a genuinely racially integrated team playing the game obsessively followed by most South Africans. 1996 has remained a very powerful memory for me over the last 17 years. However, there has always been one lingering doubt in the back of my mind: Nigeria, the reigning African champions at the time, did not participate.

The Nigerian junta’s sham trial and execution in November 1995 of author and environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa drew a sharp rebuke from then-South African President Nelson Mandela. Relations between the two countries quickly deteriorated and led to the reigning champions’ withdrawal from the 1996 tournament in South Africa. These events intensified the heated rivalry between South Africa and Nigeria. For Sunday’s final I had planned to support Burkina Faso. The Burkinabé had reached their first-ever Nations Cup final by playing exciting and entertaining football; they were also the under-dogs.

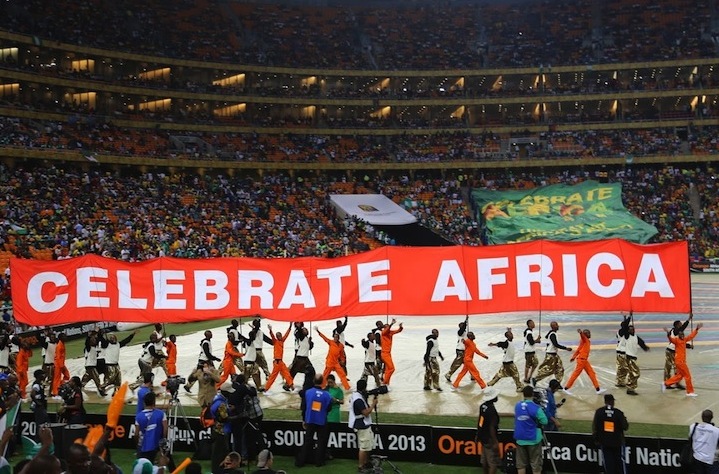

Marc Fletcher (MF): I arrived at Soccer City’s National Stadium almost four hours before Sunday’s kickoff and was pleased to see that the Nations Cup party atmosphere had finally hit Johannesburg. Considering the large Nigerian population in the city, it was unsurprising that the vast majority of the fans streaming in were Super Eagles supporters. More surprising was the significant number of South Africans choosing to support Nigeria. After all, “Nigerians” here are perceived as illegal immigrants and dangerous criminals. Tensions between African immigrant communities and South Africans have sometimes spilled over into xenophobic attacks, as in the deadly riots of 2008. But the Nations Cup final appeared to turn this association upside down; being Nigerian, or identifying with Nigeria, had become a positive thing, if only temporarily.

Walking towards the spectacular stadium, it was also apparent how this experience differed from the World Cup I attended almost three years before. Back then, football fans had been promised an “African” World Cup (whatever that entailed). South Africans and tourists alike had been repeatedly told that “It’s Africa’s Turn” and that South Africa would show the world the positives Africa had to offer. Instead, a bland, commercialised FIFA-controlled environment reduced the local flavour of the tournament to the controversy surrounding vuvuzelas. As one of my local research informants summarised, “this could be anywhere!”

Walking towards the spectacular stadium, it was also apparent how this experience differed from the World Cup I attended almost three years before. Back then, football fans had been promised an “African” World Cup (whatever that entailed). South Africans and tourists alike had been repeatedly told that “It’s Africa’s Turn” and that South Africa would show the world the positives Africa had to offer. Instead, a bland, commercialised FIFA-controlled environment reduced the local flavour of the tournament to the controversy surrounding vuvuzelas. As one of my local research informants summarised, “this could be anywhere!”

But 2013 was different. Cheaper tickets must have been a factor, allowing those who could not attend World Cup matches to engage, to experience and to celebrate. The bland hot dogs of the World Cup had been replaced with the pap and steak and boerwors rolls, staple foods at domestic matches. The relentless drumming from the small group of Burkinabé in the seats near me infused the tournament with the beat that had been lacking nearly three years ago. People of different racial, ethnic, class, and gender backgrounds socialised with one another–a dream for Rainbow Nation proponents–while the vast panoply of different African football shirts and flags reinforced a wider belonging to “Africa.” Security checks on spectators were inconsistent at best. A feeble, half-hearted pat down from a steward would do little to detect things such as flares, which constantly happens at local games (my favourite is still seeing someone pull out a full bottle of whiskey from his sock!). The pitch resembled a beach with players kicking up clouds of sand constantly. When Nigeria went ahead through Sunday Mba’s brilliant goal three-quarters of the stadium erupted in celebration. A far cry from the World Cup.

CB: Our tickets for the final were purchased months in advance, but as we tried to get to our seats it was clear that Nigerian fans occupied this part of the stadium. After stern words and persistence, we finally sat in our seats. It took stadium security and the South African police a good thirty minutes of the first half to move Nigerian fans seated on the stairs next to us to proper seats. I chatted to Sunday, a Nigerian national who told me he currently lives in Germiston on the East Rand (part of greater Johannesburg). Directly behind us was a group of eight or so trumpeters and a couple of drummers who played throughout the match. It was hard not to sway and dance to the fantastic music. By the time Nigeria took the lead my fickle allegiance was swaying towards the Super Eagles. When the final whistle blew I was happy Nigeria had won their third African title and had done so on South African soil. I look forward to Nigeria representing Africa at the Confederations Cup in Brazil later this year. But even more exciting is the prospect of South Africa regaining the lofty heights of 1996 and a show down with Nigeria. Despite Bafana’s quarterfinal exit, I carry on believing.

MF: I’ve fallen into the trap of comparing a westernised, modern, slick, commercialised World Cup with the chaotic yet dynamic African tournament. I’m not sure how to extricate myself from this other than to continue digging my hole with my romanticism of the final. It was a vibrant celebration of African football. Yet, as I drove to work this morning, the newspaper headlines attached to most Jo’burg streetlights were not about the final but Manchester United extending their lead at the top of the English Premier League. Is the 2013 Africa Cup of Nations already being forgotten?

MF: I’ve fallen into the trap of comparing a westernised, modern, slick, commercialised World Cup with the chaotic yet dynamic African tournament. I’m not sure how to extricate myself from this other than to continue digging my hole with my romanticism of the final. It was a vibrant celebration of African football. Yet, as I drove to work this morning, the newspaper headlines attached to most Jo’burg streetlights were not about the final but Manchester United extending their lead at the top of the English Premier League. Is the 2013 Africa Cup of Nations already being forgotten?

Guest Post by Marc Fletcher* (cross-posted with permission of Africa is a Country and the author.)

One of the key sights of this year’s Africa Cup of Nations has been emptiness. Aside from the opener between South Africa and Cape Verde, the television cameras have picked up images of large swathes of empty seats. Whether it was Burkina Faso’s last gasp equalizer against Nigeria in Nelspruit or Tunisia’s equally late winner versus Algeria in Rustenburg, the empty seats appeared to outnumber the fans that had made the trip. Coverage from previous editions of the tournament in Ghana, Angola and Equatorial Guinea picked up similar images. This is clearly not a South African-only problem.

I had earlier hoped that the more reasonable pricing structure for this tournament as opposed to the 2010 World Cup would have made the games more accessible to majority of poorer, working class football fans; those who make up the vast majority of the support base of South Africa’s domestic clubs. The empty seats suggest that it’s reaching few people in general.

So what are the issues behind this?

Firstly, there aren’t many players in this tournament that can be described as superstars. In the World Cup, there was Messi, Ronaldo and the entire Spanish squad. This time around, there’s Didier Drogba, whose career is winding down in China but few others. Yes, there are players such as Yaya Touré and Asamoah Gyan but they simply do not have the same star status. Why spend hard-earned money to watch two teams that you have little or no interest in?

Secondly, the 5 pm kick off times are hardly conducive to getting bums on seats. As I write this, I have one eye on the Bafana v Angola match. While attendance seems to be significantly greater than in most of the other matches, there are still many empty seats. Traffic at this time in the major cities can be nightmarish and some fans will be unwilling to put themselves through the gridlock and confusion. To make sure that you get to the stadium in plenty of time means taking the afternoon off work.

A big contributory factor is that that there are few, if any African countries that have a large fan base with a large enough disposable income to fly out to the southern tip of the continent for the tournament. Unlike the vast hoards of traveling football tourists at the Euros or at the World Cup, the support of visiting teams is usually restricted to a small rump of die-hard regular fans who are sometimes subsided by the state or political parties. While the commitment on the part of these fans is impressive, this is not going to fill these former World Cup venue. This is a problem that is not going to go away anytime soon.

But the thing that strikes me most as I write from Johannesburg is the absence of evidence that the tournament is taking place. In 2010, there were numerous posters around the city, large fan parks with big screens and people blowing vuvuzelas on street corners. Thousands crammed onto the streets in the north of the city when Bafana went on an open-top bus tour while a giant photo of Cristiano Ronaldo was emblazoned on Nelson Mandela Bridge. This time, it is severely underwhelming. There is no party atmosphere, no fan parks, little hype on local television or radio. Bafana shirts are far less apparent on the street in contrast to 2010. It’s not totally absent though. Staff at my local Spar were wearing their Bafana shirts today, while bar staff on Soweto’s tourist strip on Vilakazi Street were doing the same.

Still, it’s as if the tournament has passed Jo’burg by and I wouldn’t be surprised if it passes most of South Africa by with little more than a passing awareness that Africa’s biggest football tournament is in their country. The slogan of the tournament is “The beat at Africa’s feet,” but this beat is strangely subdued.

Maybe people realize that they have more important things to do than watch football?

N.B. During the South Africa vs Angola match, Moses Mabhida stadium in Durban seemed to be fuller in the second half. The commentator on Supersport (the South African satellite channel that dominates football broadcasting on the continent) has suggested that there is an excessive number of security cordons, which has delayed many fans from getting into the ground until the latter part of the first half.

* Marc Fletcher (MarcFletcher1), a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Johannesburg, blogs at One Man and His Football: Tales of the Global Game.

These are interesting times for politics and football in South Africa. The African National Congress is meeting this week in Bloemfontein/Mangaung to select the ruling party’s new leaders while 94-year-old Nelson Mandela is still hospitalized recovering from surgery and a lung infection. Domestic football has been rocked by a FIFA match fixing report alleging that a transnational match-fixing syndicate based in Singapore, assisted by South African Football Association (SAFA) officials, fixed Bafana Bafana’s friendlies against Thailand, Bulgaria, Colombia and Guatemala in the build up to the 2010 World Cup. Five SAFA men, including its president, Kirsten Nematandani (in photo above), have been suspended pending “further examination” of possible “criminal intent in collusion” with a front organization set up by the convicted match fixer Wilson Raj Perumal.

These are interesting times for politics and football in South Africa. The African National Congress is meeting this week in Bloemfontein/Mangaung to select the ruling party’s new leaders while 94-year-old Nelson Mandela is still hospitalized recovering from surgery and a lung infection. Domestic football has been rocked by a FIFA match fixing report alleging that a transnational match-fixing syndicate based in Singapore, assisted by South African Football Association (SAFA) officials, fixed Bafana Bafana’s friendlies against Thailand, Bulgaria, Colombia and Guatemala in the build up to the 2010 World Cup. Five SAFA men, including its president, Kirsten Nematandani (in photo above), have been suspended pending “further examination” of possible “criminal intent in collusion” with a front organization set up by the convicted match fixer Wilson Raj Perumal.

Consumed by the details of this latest sporting malfeasance as well as the tensions in ANC politics at a particularly difficult moment for South Africa, I was stunned to belatedly learn of the death of Sedick Isaacs at the age of 72. I had the extraordinary privilege to meet him in 2010 while a Fulbright Scholar at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN). I was humbled and honored to share the stage with Isaacs in a symposium on football history held on the UKZN Westville campus and sponsored by the German cultural exchange program, DAAD.

Isaacs spoke matter-of-factly about the cruelty and hardships endured during his 13 years on Robben Island. What had earned him a place in apartheid’s most notorious prison had been his role as saboteur in the armed struggle. Standing before us wearing a blue sweater in the humidity of sub-tropical Durban, Isaacs pointed out that his years on Robben Island had left him always feeling cold regardless of the temperature. A point he reiterated in Cape Town two weeks later when he spoke at my book launch for African Soccerscapes. (That’s us in the photo below.)

By studying and playing on Robben Island, Isaacs told us, prisoners formed and maintained communities of survival and resistance. He earned a university degree while behind bars and also helped to build and administer the prisoners’ Makana Football Association. (The story is admirably told by Chuck Korr and Marvin Close in More Than Just a Game: Football v Apartheid.) When the prisoners finally secured the warden’s approval for their league after three years of struggle, Isaacs ended up handling much of the day-to-day operations of the Makana FA.

Dr. Isaacs explained that the weekly cycle of matches proved crucial in fighting “eventless time” — a debilitating condition for prisoners serving lengthy sentences. The cycle worked something like this: teams started the week by analyzing the previous match and then by midweek there was growing anticipation for upcoming matches. Conversations, banter, and meetings stoked the hype and created heroes and personalities. By the weekend, excitement surrounding the matches reached fever pitch. Football’s importance, Isaacs said, was enhanced by its force as a provider of human emotions in an emotionally neutral context.

Dr. Isaacs explained that the weekly cycle of matches proved crucial in fighting “eventless time” — a debilitating condition for prisoners serving lengthy sentences. The cycle worked something like this: teams started the week by analyzing the previous match and then by midweek there was growing anticipation for upcoming matches. Conversations, banter, and meetings stoked the hype and created heroes and personalities. By the weekend, excitement surrounding the matches reached fever pitch. Football’s importance, Isaacs said, was enhanced by its force as a provider of human emotions in an emotionally neutral context.

Isaacs pointed out that the only positive effects of long prison sentences is that they can strengthen prisoners’ organizational skills and improve their understanding of human nature. The activities of the Makana FA reinforced this outcome. Intriguingly, both candidates for the ANC presidency in 2012, South African President Jacob Zuma and his challenger Kgalema Motlanthe, played football on Robben Island. “If it had not been for the beautiful game and these community building devices,” Isaacs concluded, “we could have become psychological and physical wrecks incapable of integration into a multicultural world, let alone be able to contribute positively to it.” May you rest in peace Sedick Isaacs. An exemplary South African who can teach folks in Mangaung and at SAFA a few lessons about doing the right thing in politics and football.

Banyana Banyana Win Silver: What Next?

Boosted by a home crowd of 20,000 fans, including President Teodoro Obiang Mbasogo, Equatorial Guinea crushed South Africa 4-0 in the final of the 8th African Women’s Championship in Malabo on Sunday.

Boosted by a home crowd of 20,000 fans, including President Teodoro Obiang Mbasogo, Equatorial Guinea crushed South Africa 4-0 in the final of the 8th African Women’s Championship in Malabo on Sunday.

Banyana Banyana — as the team is affectionately known — held out until the 43rd minute when the home team took the lead through Chinasa’s header from a corner kick. The goal seemed to take the wind out of Banyana’s sails. After the break the qualitative difference between the two sides became evident. Midway through the second half Banyana lost their concentration, giving up three goals in six minutes to the Nzalang Nacional (Nation’s light): Costa (66′), Anonman (70′) and Tiga (72′).

“Falling at the final hurdle is a major disappointment to all involved with Banyana Banyana,” said head coach Joseph Mkhonza at the post-match press conference. In a year that saw South Africa’s women’s team reach two major milestones, competing in the Olympics for the first time and finally beating powerhouse Nigeria, Mkhonza looked ahead and said that “Banyana Banyana should be able to qualify for international tournaments, such as the World Cup and the Olympics, in the future.”

It is always tough to play a final against the host nation, but the big game in hostile territory did appear to get the best of the South Africans. The night before the match, for example, Banyana captain Amanda Dlamini (@Amanda_Dlamini9) shared her state of mind on Twitter. “I don’t know how I’m going to sleep tonight. If I’m going to sleep at all,” she wrote. Then a few hours before the match, defender Janine Van Wyk (@Janinevanwyk5), whose marvelous goal beat Nigeria in Wednesday’s semifinal, tweeted: “Very IMPORTANT game today. I’m so nervous its [sic] insane but I know we will do well.” Perhaps adding to the pressure of the moment, the office of the Presidency (@PresidencyZA) followed by tweeting its support: “President Zuma wishes Banyana well.”

It is always tough to play a final against the host nation, but the big game in hostile territory did appear to get the best of the South Africans. The night before the match, for example, Banyana captain Amanda Dlamini (@Amanda_Dlamini9) shared her state of mind on Twitter. “I don’t know how I’m going to sleep tonight. If I’m going to sleep at all,” she wrote. Then a few hours before the match, defender Janine Van Wyk (@Janinevanwyk5), whose marvelous goal beat Nigeria in Wednesday’s semifinal, tweeted: “Very IMPORTANT game today. I’m so nervous its [sic] insane but I know we will do well.” Perhaps adding to the pressure of the moment, the office of the Presidency (@PresidencyZA) followed by tweeting its support: “President Zuma wishes Banyana well.”

That Banyana could not field three overseas players partly explains Sunday’s result. Midfielder Kylie Ann Louw and reserve goalkeeper Roxanne Barker stayed in the United States due to study commitments, while midfielder Nompumelelo Nyandeni remained with her club in Russia. “Losing a player of Nyandeni’s talent and experience will always be a setback to any team,” said Mkhonza. Another factor to consider has to do with oil-rich Equatorial Guinea’s “willingness to hand out passports to players who agree to play for them without any period of residency,” as Ian Malcolm of goal.com put it. “Almost the entire squad selected for the African Women’s Championship were born outside Equatorial Guinea, most in Brazil, but also in other African states.” While not illegal according to FIFA rules, the ethics of this all-star team formation are questionable.

The buzz about Banyana from South Africans on social media was overwhelmingly positive. “You did South Africa proud, the whole team deserves a heroes welcome. You passed all expectation and showed your greatness,” @RhandzuOptimus wrote in a tweet that captured the general tenor of South Africans’ reactions. The government chimed in too. Sports Minister Fikile Mbalula said that “Although they did not win the (African) Championships, Banyana Banyana have proven that they are an ever improving team that has shown progress over the last year.”

Now that the tournament is over what will happen to the “Banyana Bandwagon”? Practitioners and fans know that women’s football in South Africa needs much more investment and support. Even at the elite level there is no season-long national league. And as Thabo Dladla, founding director of Izichwe Youth Football in Pietermaritzburg, explains in a comment to my previous Banyana post: “There are no competitions for girls junior teams. Our girls only start playing football at the university level. These issues have nothing to do with money. SAFA should play the role in terms of promoting the game.” The road ahead is long and tortuous. We’ll be following developments closely.

Suggested Reading

Prishani Naidoo and Zanele Muholi, “Women’s bodies and the world of football in South Africa,” in Ashwin Desai, ed., Race to Transform: Sport in Post-Apartheid South Africa (HSRC Press, 2010).

Cynthia Fabrizio Pelak, “Women and gender in South African soccer: a brief history,” Soccer and Society 11, 1/2 (2010); 63-78.

Martha Saavedra, “Football Feminine—Development of the African Game: Senegal, Nigeria, and South Africa,” Soccer and Society 4, 2/3 (2003): 225-253.

Banyana Bandwagon

South Africa’s women’s national team recorded its most important victory ever on November 7 by defeating Nigeria 1-0 in the semifinal of the 8th African Women’s Football Championship in Bata, Equatorial Guinea. Defender Janine Van Wyk long-range blast gave Banyana Banyana (The Girls) their first-ever win against the six-time champion Super Falcons. South Africa will face Equatorial Guinea in the final on Sunday, November 11, a team that beat them 1-0 in the first group stage match.

South Africa’s women’s national team recorded its most important victory ever on November 7 by defeating Nigeria 1-0 in the semifinal of the 8th African Women’s Football Championship in Bata, Equatorial Guinea. Defender Janine Van Wyk long-range blast gave Banyana Banyana (The Girls) their first-ever win against the six-time champion Super Falcons. South Africa will face Equatorial Guinea in the final on Sunday, November 11, a team that beat them 1-0 in the first group stage match.

“I have been in the Banyana Banyana side since 2004 and we have tried for so long to beat the Nigerians but luck has never been on our side, but now we have proved that we can compete and beat of the best on the continent,” said Van Wyk. “At the CAF African Championship held in South Africa in 2010 I scored with a free kick from 35 metres out against Nigeria, and my teammates always remind me that I normally reserve my best for matches against Nigeria,” she laughed.

With the men’s team — Bafana Bafana — struggling, it is perhaps not surprising that South African fans and the football establishment are leaping onto the Banyana bandwagon. Following the win against Nigeria, SAFA President Kirsten Nematandani announced he would be flying out to attend the final. “The victory should open doors for the growth of women’s soccer,” he said. “Well done to the girls for making the country proud.”

With the men’s team — Bafana Bafana — struggling, it is perhaps not surprising that South African fans and the football establishment are leaping onto the Banyana bandwagon. Following the win against Nigeria, SAFA President Kirsten Nematandani announced he would be flying out to attend the final. “The victory should open doors for the growth of women’s soccer,” he said. “Well done to the girls for making the country proud.”

“We are in a very positive frame of mind going into the final game against the hosts,” said Joseph Mkhonza, the Banyana head coach. “But we are still focused on attaining our mission of taking gold in this tournament. We came here with a mission and that mission is still on track,” he said. “We have some homework to do before Sunday’s final, knowing we will play in front of a large red-clad crowd in what is certain to be a packed Malabo stadium, but we will be ready for the challenge.”

Guest Post by Chris Bolsmann (@ChrisBolsmann)

Four matches into the Premier Soccer League season and newly promoted University of Pretoria remain unbeaten. Even more surprisingly, Tuks, as the university side are known, are second on the table behind South African football giants Kaizer Chiefs. The name Tuks is derived from the institution’s original name: Transvaal University College, established in 1908. During a recent visit back to my hometown of Pretoria I watched Tuks play against city rivals Supersport United at the intimate L. C. de Villers Stadium. The uninspiring derby ended in goalless stalemate. Former national team goalkeeper, Rowan Fernandez pulled off a world-class save in the dying minutes of the game to earn Supersport United a point. This moment of brilliance was his only significant contribution but was enough to earn him the man of the match award.

I was an undergraduate student at the University of Pretoria during the volatile early 1990s. The University of Pretoria was an overwhelmingly white campus during this period with a substantial number of visible and active extreme right-wing students. It was a sign of the troubled times that the fascist Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB) essentially barred Nelson Mandela from speaking on campus. My politics classes were attended by students who left leave their 9mm pistols on their desks to either intimidate progressive lecturers or students or both.

Between 1993 and 1998 I also played football for Tukkies in the local amateur leagues. We fielded two teams and were relatively successful during this period. Our home ground was one of two fields in the enormous L. C. de Villers sports complex. Training was on Tuesday and Thursday evenings after lectures and matches on Saturday afternoons. Sunday football was deemed to violate the Sabbath and thus prohibited. The university sporting authorities were passionate about rugby but not particularly interested in football. Rugby was played on many pitches and, of course, in an impressive rugby stadium that could seat 10,000 spectators. Soccer teams weren’t issued the university regulation kit nor were we acknowledged at the end of the year sports functions.

With this history in mind, it was great to watch Tuks play PSL football at the former rugby stadium in front of a small crowd that included many black students. How things have changed at the University of Pretoria! Many of the previously sacred rugby pitches are now football fields; the football club now has teams from under 6 all the way up to the professional team. Moreover, women’s teams and university residential hall teams also play competitively.

Why the university authorities have invested substantial resources into football is perplexing. Tuks football is not a money-making venture since it attracts few paying spectators. My sense is that the University of Pretoria sees a professional football team as a marketing opportunity that helps strategically reposition itself as a premier university for all South Africans. The university has changed from its heyday as the elite training ground for Afrikaner nationalists, but as with many of South Africa’s symbols, what do we make of Tuks’s badge featuring an ox-wagon on their white shirts? Will this powerful symbol of the Boer Voortrekkers of the 1830s be reappropriated and adapted for a new era much like the Springbok survived apartheid to remain the symbol of South African rugby?