After many, many years, I recently played Subbuteo again. It was such a blast that I’m starting a series of posts on the world’s greatest football game ever invented. My older brother, who taught me how to play, kicks off.

By Daniel Alegi

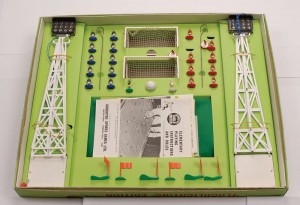

Rome, Italy, Christmas 1973: I finally got Subbuteo, the new English game everyone was talking about. It was the “Continental” set (see photo below); the box said the name was pronounced “sub-BEW-teo.” 20,000 lire ($15) got you a green cloth pitch, two white floodlights 13 inches high with 9-volt batteries, two plastic goals with brown nets, two balls, two goalies with a handle-rod and two teams in white shorts: one with red shirts, the other with blue.

“Italy – Russia!” I said. “Como-Varese!” said my brother from the height of his 18 months’ seniority. Their kits are almost identical, but would you rather make your debut in the Christmas snow at Moscow’s Lenin Stadium or in a Serie B derby in the Po Valley fog? Our first flicks were backed by our grandfather in the armchair snoring away. Cloth pitch on the carpet, improvised rules. Then during lunch dad stood up and stepped on everything (how could he miss a 4.5ft x 3ft pitch?). On the ground lay decapitated, amputated, crushed players. Only six survived this massacre, one of them a goalkeeper. And so with this ill-fated 1973 debut, played with only one goal, Subbuteo entered our house forever.

Category: Players

Luis Suarez has been banned for 8 games in the English Premier League for the alleged racist abuse of Patrice Evra. The nature of the exchange between Luis Suarez and Patrice Evra has not yet been disclosed. Luis Suarez is appealing. Here is a brief reminder of a less well known contribution Luis Suarez made to the World Cup in South Africa. A post on Luis Suarez will follow once details of the accusation against Suarez have been released by the English FA.

Stryker-Indigo New York, a private multi-media film and print production company, has announced the acquisition of a major collection of 1950s-1960s 8mm and 16mm soccer films.

Stryker-Indigo New York, a private multi-media film and print production company, has announced the acquisition of a major collection of 1950s-1960s 8mm and 16mm soccer films.

The film footage, featuring both university and international teams playing in American cities, contains rare home movie images of the history of the game in the United States. For example, there is footage of the first leg of the 1961 U.S. Open Cup Final between United Scots of Los Angeles and Ukrainian Nationals of Philadelphia at Rancho La Cienega Stadium in LA (now Jackie Robinson Stadium).

According to the Stryker-Indigo web site, its Futbol Heritage Archive houses nearly 9,000 historic photographs, slides, newspaper clippings, postcards, trophies, jerseys and artifacts. Following the closure of the US Soccer Hall of Fame in Oneonta, NY, researchers have lost access to an archive of more than 80,000 items, including the North American Soccer League archive and the 1994 World Cup archive. It is hoped that private collections such as Stryker-Indigo’s film footage will be made accessible to soccer researchers and aficionados so that the history and culture of the game can be properly recorded and disseminated.

***

Thanks to David Wallace for inspiring me to write this post.

Spotlight on African Coaches

Editor’s Note: This post begins a multi-part series on African coaches.

Continuing with Pitso is Regressing

Guest Post by Mohlomi Maubane

SOWETO, SOUTH AFRICA — In a recent issue of Kick Off, South Africa’s leading soccer magazine, Editor Richard Maguire argued against firing Bafana Bafana coach Pitso Mosimane (in photo above). Pitso, of course, is singularly responsible for South Africa’s embarrassing failure to qualify for the 2012 African Nations Cup finals (aka The Comedy in Nelspruit). I have been collecting Kickoff since high school. As a magazine, it expects vision, competence and innovation from every member of the South African football fraternity; hence the editorial vouching for Pitso to stay on as Bafana Bafana coach was surprising.

The crux of Maguire’s argument is that Mosimane should remain in charge for the sake of continuity. I say there should not have even been a beginning. Mosimane’s coaching success has been overblown. At club level, he led well-endowed Supersport United to five cup finals, losing three, and at national team level he was an assistant coach during a mediocre run from 2006 to 2010, when Bafana sunk to 90th in the FIFA World Rankings.

The ridiculous manner in which South Africa failed to qualify for the 2012 African Nations Cup finals showed Mosimane to be as unprofessional as his employers. How can a national coach fail to read or grasp competition rules? This is a man who thinks of himself as a “modern” coach always in step with the latest developments in the world game. Perhaps common sense is not part of the curriculum of the courses Mosimane often brags of attending. And for all his supposed keeping abreast with the latest trends in the game, Mosimane’s idea of “global football” is confined to the English Premier League and La Liga.

SAFA appointed Pitso Mosimane as Bafana Bafana coach soon after the 2010 World Cup. At the time, there was talk of the dawn of a new era in South African football. In truth, there was the usual lack of specific detail on how to make this new epoch come about. Instead, SAFA officials spoke at length about Vision 2014, Bafana Bafana’s campaign to qualify for the World Cup in Brazil. The seven other national teams under SAFA’s auspices were left unmentioned. Now, a year after the Vision 2014 was unveiled, we are a joke in the football world.

More than anyone else, it was Mosimane’s job to ensure Bafana qualified for 2012. He was entrusted with the troops and should have known the rules of engagement. When he was introduced as the new Bafana coach after the World Cup, Mosimane was his typical pompous self, saying he did not expect favors from anyone, he knew his mandate, and that he wanted to be judged by the results. Here are the Nations Cup results: 2 wins, 3 draws, and 1 loss, 4 goals scored, 2 against. Having failed to qualify, his story has now changed. In his first press conference after the Comedy in Nelspruit, Mosimane had the audacity to say he did not fail because South Africa finished top of their group! That Bafana actually failed to qualify was in the past; it was time to move on, he said.

Indeed it is time to move on, and perhaps it is best to do so with a coach who reads and understands the rule book; one whose trophies and coaching acumen supersede his chest-thumping bravado. Pitso Mosimane has been in the national structures for more than five years and South African football would not be served well by a continuation of his underachievement.

If Mosimane were a football journalist and wanted to write for Kick Off, I suspect Maguire would send him away with the disdain he probably feels when the magazine has to document yet another SAFA cock-up.

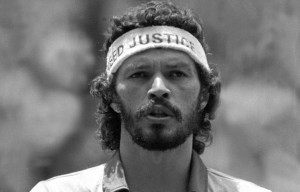

Socrates of Brazil is Gone

Barcelona, 5 July 1982: Paolo Rossi had just headed in an Antonio Cabrini cross to put us up 1-0 against Brazil in the last game of the second group stage of the 1982 World Cup. My friend Fabio and I, football-obsessed youngsters, sat wide-eyed on the floor of an impossibly crowded living room in a relative’s home outside Pesaro, in the hills of the Marche region of Italy. A few days before we had been part of a spontaneous street carnival with tens of thousands of fellow Romans celebrating our victory against Maradona’s Argentina. Rossi’s goal suddenly made a miracle possible: beat Brazil and earn a place in the semifinals.

Five minutes later, a Brazilian Doctor made an incision that surgically removed the optimism of hope. Socrates, we knew from watching Corinthians games on Teleroma 56 (a local station), had a penchant for embarrassing defenders with graceful pivots on the ball and elegant heel passes. To say nothing of goalkeepers humiliated by his swerving free kicks and shots from impossible angles.

That hot July afternoon on the pitch of Español’s Sarria Stadium, Socrates received the ball in midfield, carried, dished it off to Zico and continued his run forward. With the outside of his right foot, Zico quickly sliced a delightful pass to a streaking Socrates in the box. Socrates took a simple touch and appeared to be running out of room on the right side of the 6-yard box. Where most players would square the ball back into the middle of the box for a teammate to run on and strike at goal, Socrates instead took a precise near-post shot that faked Dino Zoff out of his shorts: 1-1. No! He didn’t just do that?! Watch it here. (Italy went on to win the game 3-2 and the World Cup.)

After the 1982 tournament, Corinthians traded Socrates to Fiorentina so we got to appreciate the fullness of this grandiose footballer for many years. Even Juve fans like me, whose contempt for La Viola is unrestrained, became fond of “Tacco d’Oro” — the Golden Heel — the tall, lanky, bearded midfielder with the long curly hair who added so much spectacle to Serie A in the age of Maradona, Platini, and Falcao.

A decade later, I found myself still learning from Socrates but in a completely different context. While teaching one of the first undergraduate courses on soccer ever taught in an American university, my students and I discussed Socrates’s role in Corinthians Democracy, a movement that helped propel democratic change in Brazil in the early 1980s. How many professional athletes would threaten to retire, as Socrates did in 1982, if a conservative businessman were to take the reins of a popular team?

So it was with profound sadness that I learned of Socrates’s passing at the age of 57. The official cause of death was “septic shock from an intestinal infection” according to a São Paulo hospital statement. Like Garrincha, Brazil’s most loved footballer, Socrates was an alcoholic. The rum-like cachaça had become his vital fluid. As Socrates candidly put it in an interview: “This country drinks more cachaça than any other in the world, and it seems like I myself drink it all.” We all battle our demons.

As the South Africans say, “Hamba kahle” brother Socrates. Your love of the game and commitment to social justice will never be forgotten.

Suggested reading:

Matthew Shirts, “Socrates, Corinthians, and Questions of Democracy and Citizenship,” in Joseph Arbena, ed., Sport and Society in Latin America: Diffusion, Dependency, and the Rise of Mass Culture (New York: Greenwood Press, 1988), pp. 97-112.

Simon Romero’s poignant obituary of Socrates in the New York Times is here.

“Playing the Game”

“Playing the Game” by Sophie Alegi

Chests heave

Legs run

Tendons work

Bones stretch and pull

Muscles bulge

Brains flash in a spark of neurons

Sweat drips.

The defender tears a tendon trying to steal the ball.

The midfielder blows past a defender in a flash of speed.

And the forward collects the ball and shoots.

The goalie stretches all of her fibers to catch the ball.

But it slams into the net.

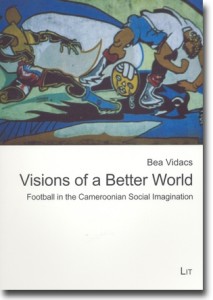

The 1990 World Cup hosted by Italy is often remembered for the exploits of Cameroon’s Indomitable Lions. Led by 38-year-old striker Roger Milla, Cameroon legitimized African football on the global stage with their 1-0 victory over Maradona’s Argentina in the opening game and then becoming the first African team to reach the World Cup quarterfinals. In 1994, Bea Vidacs, a Hungarian anthropologist based in the United States, landed in Yaoundé to begin her research on football and identity in Cameroon. Visions of a Better World: Football in the Cameroonian Social Imagination is a revised version of a doctoral thesis completed in 2002, a study that over the years midwifed several very good journal articles and chapters in scholarly collections.

Read my full review at H-Soz-u-Kult.