Guest Post by “Er Prof”

ROME–This past Sunday at the Stadio Olimpico I screamed in honor of Michael Bradley’s first serie A match with “La Magica Roma.” I howled so much during the 2-2 draw with Catania that I’m still hoarse three days later.

I am proud to say that I yelled only encouraging, positive things because I had my two boys, Alberto (age 9) and Luca (age 6), with me in the “Family” section of the Distinti Nord. (Long gone are my days with the Commando Ultrà Curva Sud.) In truth, I was also heeding my wife’s warning that if the kids returned home swearing she’d kick me out of the house.

It was so beautiful to see Luca absolutely mesmerized by the stadium atmosphere and the chaos; Alberto got into it too, especially after we drew level and he started believing in a miraculous victory even more than me.

There are at least two ways to comment on what happened in this strange opening game of the 2012-13 season. The first draws on the “dietrologia” (“behindology”) typical of the frustrated Romanista of the post-Capello era: “there you go, Zeman speaks the truth [about corruption and other ills affecting calcio] and those goddamn refs nail us immediately: Catania’s two goals were ludicrously offsides; we were denied a clear penalty; and Osvaldo was, absurdly, deemed offside on a breakaway that would have, surely, resulted in a goal. Two stolen points to keep those Juve bastards calm and content.”

Somehow I managed not to insult the referee for the entire ninety minutes, despite the time-tested knowledge that when in doubt referees always make important calls against us. It may sound like bullshit, but accepting this disgusting (“schifoso”) state of affairs is a big step forward for us as we move towards a different future, one defined by clean, clear, decisive victories achieved in spite of crooked referees.

The second way to reflect on the game is calmer, the kind possible only after the game; it is more focused on the sporting side of things. In the first half, La Roma played like utter shite. The team seemed confused and also intimidated by Catania’s toughness and fitness (a team with nine Argentineans!). Totti and Lamela were almost invisible; Bradley tactically too horizontal; De Rossi couldn’t deliver a vertical pass; and Piris shanked every cross. In the second half, La Roma started playing more seriously, but only through Florenzi and the 19-year-old Uruguayan Nico Lopez did it become truly dangerous. Shortcomings aside, we deserved to win handily. And we would have had it not been for the five officials: five pairs of eyes that managed to miss amazing offsides on Catania’s goals and an incredible handball in their box.

At halftime a child in our section asked his father why we were losing. The man replied with extraordinary wisdom: “because we were born to suffer” (“perchè semo nati pè soffrì”). That was a damn good answer, but the best line may still be the graffiti etched on a wall in our Eternal City: “VIVA LA PAZZA GIOIA D’ESSE ROMANISTIII” (“Long live the crazy joy of being Romanisti”).

Category: Players

Guest Post by Chris Bolsmann (c.h.bolsmann [at] aston [dot] ac [dot] uk)

COVENTRY–In a week when South African cricketers and golfers recorded convincing victories, a hat trick of results would have seen South Africa’s women’s national team celebrate their first appearance at the Olympic Games by beating Sweden. But facing a team ranked 4th in the world, Banyana Banyana (Zulu for “the ladies”) could not pull off the miracle win.

The South Africans met their Swedish counterparts in Coventry, 100 miles north of London, in the second match of a double header. Japan beat Canada 2-1 in the early game in front of 18,000 spectators, while the 2011 World Cup third-place finishers defeated South Africa 4-1.

Normally called the Ricoh Arena and home to Coventry City FC, the City of Coventry Stadium looked quite different from its normal appearance full of advertising hoardings. The Olympic organisers were not quite able to cover up all of Coventry City’s history though, as a photo of the 1987 FA Cup winning team adorned one of the stadium walls.

While Banyana Banyana have always worn the yellow and green colours of the South African Football Association, this time the squad entered the pitch in a horrible-looking green and white vertically striped kit, courtesy of the South African Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee’s official kit supplier: Erke, from China. The crowd had dwindled to a few thousand for the second match and the majority of photo press had left the stadium. A small contingent of South African fans remained who were vocal throughout but were outnumbered by Swedish fans and locals who supported their European neighbours.

Sweden kicked off and, ominously, twice hit the cross bar in the opening six minutes. The Scandinavians went ahead in the 7th minute thanks to a Nilla Fischer shot from outside the box that was cruelly deflected past United States-based Roxanne Barker in the South African goal. Then the Swedes again hit the cross bar and doubled their lead in the 20th minute when Lisa Dahlkvist poked home a ball from the flanks. A minute later Sweden scored a third goal when South African stalwart Janine van Wyk was beaten for pace on a through ball and Lotta Schelin slotted past the on rushing South African keeper. After 21 minutes Banyana’s debut had turned into a nightmare and a real humiliation was on the cards.

The South African midfield were constantly over run by the more forceful and creative Swedes and the defence were outpaced on numerous occasions, allowing for the Swedes to cross balls into the box at leisure. To her credit, Barker dealt well with crosses and high balls and remained calm under constant Swedish pressure.

The second half saw Banyana kick off with far more purpose and creative intent. In the 60th minute, Portia Modise, a former World Player of the Year nominee, dispossessed a Swedish midfielder well within the South African half and from inside the centre circle unleashed a wonderful strike to beat Hedvig Lindahl. Modise’s goal restored South African spirits and momentarily gave South African supporters some hope. But three minutes later Schelin got her second goal of the match and restored the three-goal margin.

The final quarter of the game saw South Africa struggle with fitness and the match ended with a resounding victory for the Swedes. Sweden had over 57% possession and outshot South Africa 21 to 7. Banyana Banyana were outclassed by a technically superior and fitter Swedish side. After the shock of allowing three goals within 25 minutes, Banyana settled and showed a few individual moments of skill but were unable to retain possession for any length of time. It won’t get any easier in this tournament for South Africa: they face Canada on Saturday and World Champions Japan the following week.

On Friday, Howard Riddle, Senior District Judge in the Westminster Magistrates’ Court, found Chelsea captain John Terry not guilty of racially abusing Queen’s Park Rangers Anton Ferdinand. Here are eight things I learned by reading Judge Riddle’s decision:

1. “There is no doubt that John Terry uttered the words ‘fucking black cunt’ at Anton Ferdinand” (p.13).

2. TV footage unequivocally demonstrates that “Terry directed the words ‘black cunt’ in the direction of Anton Ferdinand” (p.3).

3. In a statement to the English FA Terry 5 days after the incident, remembered saying to Ferdinand “I think it was something along the lines of, ‘You black cunt, you’re a fucking knobhead'” (p.10).

4. Lip reading experts are amazing people who do important work, but this doesn’t mean much in the big picture.

5. Terry said what he said in the heat of the game and was angry, physically and mentally tired (pp.13-14). Seriously.

6. Give money to a charity in Africa: it’s a great alibi (as Elliot Ross explains here).

7. That nobody on the pitch claims to have heard Terry calling Ferdinand a “fucking black cunt” at the time and that “there are limitations to lip reading” [p. 14]) was used to obfuscate the undisputed factual evidence of the video footage.

8. The “not guilty” verdict reflects tortuously twisted logic. The decision seems to hinge on the possibility that Terry hurled the insult at Ferdinand only after the latter had “accused Mr Terry on the pitch of calling him a black cunt” (p. 14). “It is therefore possible,” Judge Riddle concludes, “that what he said was not intended as an insult, but rather as a challenge to what he believed had been said to him” (p. 15). So let me see if I understand this legal reasoning correctly: it is not racially abusive speech to call a black person a “fucking black cunt” if it’s in response to an accusation of calling you a fucking black cunt. Huh?

As @NutmegRadio eloquently tweeted: “The John Terry verdict now stands as a how-to-guide for how to escape a racially aggravated public order offense in the UK.”

Spain: The Greatest Team Ever?

Euro 2008, World Cup 2010, and now Euro 2012 champions. Spain’s 4-0 demolition of Italy in yesterday’s final in Kiev secured their third consecutive major tournament victory in the last four years. The question many are asking today is whether La Roja is the greatest team in the history of football.

Euro 2008, World Cup 2010, and now Euro 2012 champions. Spain’s 4-0 demolition of Italy in yesterday’s final in Kiev secured their third consecutive major tournament victory in the last four years. The question many are asking today is whether La Roja is the greatest team in the history of football.

Hundreds of millions of TV viewers watching the final in pubs, homes, and public venues around the world witnessed Spain’s best performance of the Euros. Propelled by Xavi’s sudden resurgence and Del Bosque’s flawless tactics, lineup, and game management, the Spanish tiki-taka approached a near-perfect synthesis of art and science. Meanwhile Italy’s tired legs and coach Prandelli’s naive decision to deploy 2 strikers, no defensive midfielders, and field injured Chiellini, De Rossi and even Motta (as a final substitute!) exposed the substantial qualitative gap separating the two finalists.

While my emotional wounds from enduring such a hideous hiding are still raw, I’m interested in what people have to say about how Spain 2008-12 compares, say, with Brazil 1970? Germany 1972-74? Or even Uruguay 1924-1930 and Hungary 1950-54 if we delve into a radically different media era? Should we consider club teams too? Real Madrid 1955-60, Ajax 1971-73, Milan 1989-90, and Barcelona 2009-2011 immediately come to mind.

Here are my top 5:

1. Uruguay 1924-30 (winners of 1924 & 1928 Olympics and 1930 World Cup)

2. Spain 2008-2012

3. Brazil 1970 (good case for the best ever, but won only one title)

4. Hungary 1950-54 (undefeated, 42 wins and 7 draws).

5. Barcelona 2009-11 (FIFA Club World Cup: 2009, 2011; Champions League: 2008–09, 2010–11; UEFA Super Cup: 2009, 2011; La Liga: 2008–09, 2009–10, 2010–11; Copa del Rey: 2008–09, 2011–12; Supercopa de España: 2009, 2010, 2011)

What do you think? Share your rankings in the comment section!

Afritalians: Past is Prologue

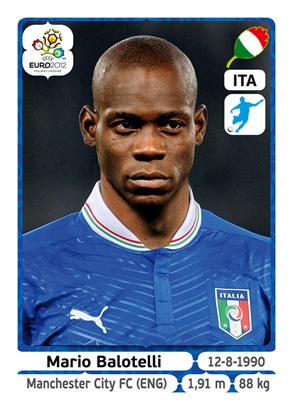

The Africanization of Italy may have started 2200 years ago as Hannibal of Carthage led his troops and elephants across the Alps on the way to Rome, but Mario Balotelli’s two-goal performance in Italy’s defeat of Germany in the Euro 2012 semifinal may be mainstreaming it.

The Africanization of Italy may have started 2200 years ago as Hannibal of Carthage led his troops and elephants across the Alps on the way to Rome, but Mario Balotelli’s two-goal performance in Italy’s defeat of Germany in the Euro 2012 semifinal may be mainstreaming it.

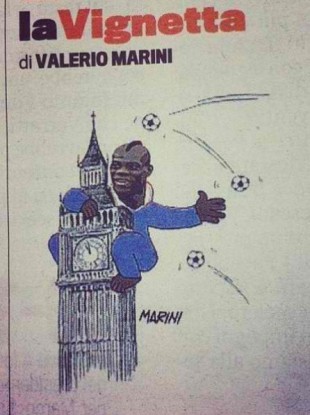

Italians across the political spectrum are gushing in their praise of the 21-year-old striker. “Pride of Italy!” screamed the web site of La Gazzetta dello Sport, which earlier in the week had printed an insulting cartoon of Balotelli as King Kong by Valerio Marini (see below). (Despite an outpouring of criticism from readers and on social media, the paper could only muster this sad excuse for an apology: “if certain readers found the cartoon offensive, we apologize.”)

Earlier in the tournament Balotelli had won accolades for his acrobatic overhead strike against Ireland and for his impeccable penalty which opened the shootout against England (scored against Man City teammate Joe Hart). Now, on the eve of the final against Spain in Kiev, ordinary Italians and the media are comparing Balotelli to Gigi Riva, Totò Schillaci, and Gianluca Vialli — illustrious Azzurri of the past who transcended the football pitch to become popular icons of national culture. A big and very noticeable difference between Super-Mario and his predecessors, of course, is that Balotelli is black — the Palermo-born son of the Barwuahs from Ghana who was adopted by the Balotellis of Brescia. He is the first Afritalian football superstar.

Super-Mario’s central role in potentially ushering in a new phase in the Africanization of Italy is reflected in Italian media stories highlighting how Mario is like you and me: he loves football, family, pizza, and hanging out with his friends. In a country where mothers are sacred and where the Virgin Mary is venerated almost as much as her more famous son, Mario’s loving embrace of Mamma Silvia in the stands at the Warsaw stadium shot an arrow into the heart of every Italian. “Boastful and ‘mammone’, Balotelli represents the prototype of the Italian,” wrote Il Giornale, a conservative paper owned by Silvio Berlusconi’s brother, Paolo.

And Balotelli is not an isolated case; he’s not even the only Afritalian in the Euro squad. Sitting on the reserves’ bench is 24-year-old Angelo Obinze Ogbonna (at left), a central defender who plays his club football for Torino. Born in Cassino, near Rome, of Nigerian parents, Ogbonna was recruited into the Torino youth academy at age 14 and played his first serie A match at 19. Like Balotelli, Ogbonna speaks Italian without a trace of accent. The experiences of Super-Mario and Ogbonna open up an opportunity to consider the history of Afritalian footballers.

And Balotelli is not an isolated case; he’s not even the only Afritalian in the Euro squad. Sitting on the reserves’ bench is 24-year-old Angelo Obinze Ogbonna (at left), a central defender who plays his club football for Torino. Born in Cassino, near Rome, of Nigerian parents, Ogbonna was recruited into the Torino youth academy at age 14 and played his first serie A match at 19. Like Balotelli, Ogbonna speaks Italian without a trace of accent. The experiences of Super-Mario and Ogbonna open up an opportunity to consider the history of Afritalian footballers.

Let’s start with Claudio Gentile. He was born in Tripoli, the son of a Sicilian father and a Tripoli-born mother possibly of Italian background, and grew up playing street football in Libya before moving to Como in 1961 with his family. Nicknamed “il libico,” Gentile had his best years at right back for Juventus and Italy in the 1970s and early 1980s, forming with Dino Zoff, Antonio Cabrini, and Gaetano Scirea one of the stingiest defensive lines of all time. Gentile’s ferociously effective man-to-man marking of Maradona and Zico in the 1982 World Cup, which Italy won, has become the stuff of legend.

We had to wait nearly two decades for the next Afritalians to make an appearance in the national team. In 2001, Fabio Liverani, the Rome-born son of a Somali mother and Italian father, made his international debut in a friendly against South Africa. Despite a solid career as a midfielder with Lazio, Fiorentina, and Palermo, Liverani only played twice more for the Azzurri. Around the same time, Matteo Ferrari, the Algeria-born son of an Italian father and a Guinean mother, played eleven times in the heart of Italy’s defense. Prior to Balotelli’s success, Ferrari had held the record for most international appearances for an Afritalian. (He now plays for the Montreal Impact in MLS.)

There are other players of African blood in Italian football. Among them, Stephan El Shaarawi, Stefano Chuka Okaka, and Fabiano Santacroce (of Afro-Brazilian/Italian parentage) have been capped at junior level. There is also a female Afritalian: left back Sara Gama (at right), who also earned the distinction of becoming the first Afritalian woman to captain the U-19 national team, and leading them to the 2008 European title.

There are other players of African blood in Italian football. Among them, Stephan El Shaarawi, Stefano Chuka Okaka, and Fabiano Santacroce (of Afro-Brazilian/Italian parentage) have been capped at junior level. There is also a female Afritalian: left back Sara Gama (at right), who also earned the distinction of becoming the first Afritalian woman to captain the U-19 national team, and leading them to the 2008 European title.

Mauro Valeri, a sociologist and author of La Razza in campo: Per una storia della Rivoluzione Nera nel calcio (EDUP, 2005) wonders if the increasing presence of black players at junior and senior level is “perhaps a sign of a transformation underway, of the affirmation of a Black Revolution [in football] that for more than a decade has been unfolding in Italy.” While structural changes would be necessary for such a shift to be lasting and meaningful, social perceptions of Afritalians may be changing thanks to Balotelli’s sudden popularity. In a grim age of austerity and structural adjustment, Italians seem eager for another taste of Super-Mario-triggered football euphoria.

Guest post by Mohlomi Maubane

The Germans regularly find a way to excel in tournaments and are among the favourites to win the Euros in Poland/Ukraine. The South African football fraternity would do well to take a page out of the playbook that produced the current incarnation of Die Manschschaft when appointing a new Bafana Bafana coach. SAFA fired Pitso Mosimane this week after Bafana Bafana could only muster a 1-1 draw against Ethiopia in a 2014 World Cup qualifier in Rustenburg.

Eight years ago, the German national team was in dire straits after failing to win a single match in the group stages of the 2004 Euros. A rebirth seemed inevitable, and the newly appointed technical team of Jürgen Klinsmann and Joachim Löw pursued it with typical German precision.

Their first step was to give Die Manschschaft a new identity. The duo settled on a style based on playing the ball on the ground and transitioning swiftly from defence to attack. This was the outcome of an extensive consultation process. Workshops were held with German coaches and players to inquire how they wanted to play and how they wanted to be seen to be playing by their fans (and international ones too). Members of the German public also enjoyed the opportunity to provide input on how they wanted the national side to play.

From this inclusive process, Klinsmann and Löw drafted a curriculum for German football that was presented to the Bundesliga and the German FA. The latter then pressured teams in the former to build academy programmes that adhered to the overall strategy. Bundesliga teams were also encouraged to adopt a fitness programme that enabled the philosophy to be implemented. The newly appointed Under-21 coach also had to abide by the new policy.

The Italian Job: Revisited

Police raid the Italian national team camp and an earthquake in Emilia-Romagna forces the cancellation of the Italy-Luxembourg Euro warm-up. It’s been a tough week for Italian tifosi, on and off the pitch.

Defender Domenico Criscito left the Euro squad after being implicated in the latest wave of prosecutorial investigations and charges. Meanwhile, Antonio Di Natale emerged as a pale as a ghost after riding out the 5.9 magnitude quake in an elevator.

The latest developments in calcio’s corruption and match fixing scandal have produced 19 arrests, including that of Lazio captain Stefano Mauri and ex-Genoa man Omar Milanetto. Prosecutors in Bari, Cremona, and Napoli have also implicated several dozen high profile players, managers, and club officials. That this mess is taking place only a few years after “calciopoli” — which famously landed Juve in serie B and penalized Milan, Lazio, and Fiorentina — is a potent indictment of the Italian football system and its willingness or ability to reform itself.

Italian authorities and prosecutors inspire confidence in some circles that the metastasizing problem will finally be addressed (read Declan Hill’s blog post here), but I find this optimistic view problematic on a number of levels. Here’s why:

First, the justice system in Italy is utterly dysfunctional. From civil to criminal cases, almost nothing works properly. The country has more than 10,000 laws on the books, that’s more than most, if not all, other countries in the world. Moreover, culprits of egregious crimes are often let off the hook with little more than a slap on the wrist while minor cases take years to resolve. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Second, calcio works exactly like Italian politics. Family and “big man” cliques dominate and actively seek to expand their narrow interests against the common good. From serie A and B all the way to the lowest amateur ranks, this situation makes it almost impossible to develop a fair, equitable, and sustainable solution to the football rot.

Third, Italian sport and society struggle with a culture of cheating that pivots around what may be labeled “situational ethics” and a common sense rationalization that laws are made to be circumvented.

Given this dispiriting local situation and a worrisome rise in match fixing, corruption, and bribery on a global level, the Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti’s recent statement “that it would really benefit the maturity of us Italian citizens if this game was completely suspended” for a couple of years seems like a good idea. It might create the space needed for a soul-searching dialogue aimed at finding long-term solutions to calcio’s spiral of decline.