On Sunday, January 5, Eusébio died of heart failure in Lisbon at the age of 71. Born Eusébio da Silva Ferreira in 1942 in what is today Maputo, Mozambique, he became the first African player to acquire global fame. Portugal has declared three days of national mourning in his honor. As per Eusébio’s wish, his coffin was carried to the center of the pitch at Benfica’s La Luz Stadium in an extraordinary ceremony on Monday (see video above). Fans created a memorial that enveloped his statue outside the stadium.

The striker’s standing in the game’s history was celebrated in two excellent obituaries published in today’s New York Times (read them here and here). Many would agree though that the most poetic tribute to Eusébio comes from Eduardo Galeano (click here to listen to the author read it).

Like most African boys, Eusébio grew up kicking makeshift footballs in the streets. As a teenager, he failed a trial with Desportivo, Benfica’s Mozambican subsidiary, because he showed up without proper boots so he joined rival Sporting instead. His big break came when he scored twice against Ferroviara de Araraquara from Brazil, which was touring Mozambique. José Carlos Bauer, the Ferroviara coach and a former member of Brazil’s World Cup team recommended Eusebio to Bela Guttmann, the legendary coach of Benfica. Guttmann was an ardent believer in overseas players and a globetrotting emigrant himself.

In 1961 Benfica signed Eusébio for £7500. Fast and strong, he had that rare combination of mobility, long-range shooting ability, and a striker’s instinct close to goal. These qualities, according to David Goldblatt, made him “perhaps the archetype of the modern football player.” He won 7 league titles , 2 Portuguese FA Cups, and a European Cup. In 1965 he was crowned the best player in Europe, three decades before Liberian striker George Weah, and was top scorer in the 1966 World Cup with nine goals.

He was idolized in Portugal and throughout Africa. His statistics spoke volumes: 317 goals in 301 matches with Benfica; 41 in 64 for Portugal—a record Cristiano Ronaldo has yet to surpass. Together with Pelé, Eusébio was instrumental in elevating the status of black players in world football. He “destroyed the nonsense that Africans could not play soccer—or rather could not learn to harness individual flair for the good of the team,” wrote Rob Hughes in the New York Times. He also exemplified how African labor benefited Portuguese football by providing athletic talent at affordable prices and making it more cosmopolitan.

“Eusébio represented a confident, glamorous, mobile new Africa on the world stage,” Sean Jacobs and Elliot Ross noted in their poignant tribute for Al Jazeera America. “But his remarkable historical achievement was to be the face of not one but two emerging continents. He helped, in his own way, to reshape the idea of Europe itself.”

—

This post draws on material from my book African Soccerscapes: How a Continent Changed the World’s Game (Ohio University Press, 2010).

—

Suggested Viewing/Reading:

Eusébio – Um Jogador de Todos os Tempos (documentary, in Portuguese)

Farewell Eusébio by Sports Illustrated’s Planet Fútbol

“Remembering Eusebio’s brief time in the NASL” by James Tyler with Shep Messing

Category: Video

Guest Post by Khaya Sibeko (@KhayaSibeko1)

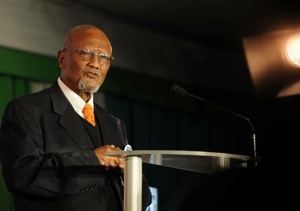

JOHANNESBURG—On October 30, 2013, Leepile Taunyane, South Africa’s legendary football administrator, died at the age of 85. It would not be an exaggeration to compare his passing to the burning of a national archive.

Born in Alexandra, Johannesburg, Taunyane grew up playing football in the streets and then joined Rangers in the early 1950s, a club known for its technical prowess and feared for its lineup stacked with ex-convicts. After hanging up his boots, in the 1960s Taunyane started a career as a football organizer and served as principal first at Alexandra High School and then at Katlehong High.

His administrative career saw him involved in every major transformation in the South African game. Taunyane worked with Bethuel Morolo at the South African Bantu Football Association and then with his successor, George Thabe. In the mid-1980s, an era of massive political and social upheaval in apartheid South Africa, Taunyane led the Transvaal affiliate of Thabe’s Africans-only organization to throw its weight behind the National Soccer League. A precursor of today’s Premier Soccer League, the NSL was a new, racially integrated league launched in 1985 as a break away league from Thabe’s NPSL. Taunyane became the NSL’s first president.

In a recent City Press article, Premier Soccer League and Orlando Pirates chairperson, Irvin Khoza honored his mentor: “I was his student when he was a teacher. He recruited me at the tender age of 14 to become a member of the Alexandra Football Association. We later rubbed shoulders in the national league and federation structures. Dr. Taunyane personifies the values that govern my decision-making and actions, consciously and unconsciously.”

Taunyane was “the last of the Mohicans” of football administrators of a venerable generation. Even when others around him found the temptations of post-isolation football too much to resist, Taunyane remained a diligent and incorruptible servant of the beautiful game. It was no surprise when, a few years ago, the PSL bestowed the honorific title of Life President.

It is not enough to celebrate and award titles, of course. By publicly recognizing Taunyane’s great legacy, local football administrators should strive to follow his exemplary managerial conduct. That would be the best way to remember and honor a “son of the soil” who spared neither time nor energy in the service of football and education.

Undoubtedly, the gods of South African football have placed Taunyane alongside Bethuel Mokgosinyane, Solomon Senaoane, Dan Twala, Albert Luthuli, Henry Ngwenya, George Singh and so many elders of the distant past, men whose efforts shaped our football in the era of segregation and apartheid. Without the contributions of men like Taunyane, South Africa would never have hosted the 2010 World Cup and the PSL would not be among the ten richest leagues in the world.

Punk Football for the Working Class

We play therefore we are.

That, in essence, is the sentiment that motivated a group of disaffected Red Devils’ fans opposed to Malcolm Glazer’s $1.5 billion takeover in 2003 of Manchester United to quit Old Trafford and form a new club: FC United of Manchester.

Punk Football, a terrific and profoundly humanistic new documentary film, chronicles FC United’s dramatic 2012-13 campaign which brought them to the brink of promotion to the North Conference League—five levels below the glitz and glamor of the English Premier League.

We are introduced to FC United supporters, officials, players, and coaches who explain what it means to be a community football club owned and democratically run by 2825 co-owners, each holding one voting share. FC United’s manifesto makes it clear this is football by the people, for the people. Football for the working class. “FC United seeks to change the way that football is owned and run, putting supporters at the heart of everything,” states the club’s website. “It aims to show, by example, how this can work in practice by creating a sustainable, successful, fan-owned, democratic football club that creates real and lasting benefits to its members and local communities.”

Around the time of the film’s release, construction began on FC United’s new 5,000-capacity stadium. After wandering for years playing home matches at rented grounds, most recently at Gigg Lane in Bury, members raised more than £2m through a share scheme, and secured additional funding from Sport England, the Football Foundation, the City of Manchester, and Manchester College. (Click here for a recent news story about the stadium.)

The extraordinary story of FC United putting people and poetry before profits is beautifully told in this brilliant documentary. Don’t miss it!

Boca Júniors’ “Fraud of the Century”

On October 3-4, Alex Galarza spoke at the Rethinking Sports in the Americas conference at Emory University about the history of Club Atlético Boca Júniors’ Ciudad Deportiva (“sports city”), a gargantuan urban project hailed in the 1960s as a harbinger of national progress and modernization that later became known as the “fraud of the century.” Galarza is a doctoral student in history at Michigan State University and co-founder of the Football Scholars Forum. This paper is part of ongoing doctoral research funded by the Fulbright Program and a FIFA Havelange Scholarship.

The scholarly gathering in Atlanta provided ten early career scholars and graduate students with a chance to present new research papers and receive feedback from peers and senior scholars. Participants read and commented on pre-circulated papers, which made for lively and engaging discussions. Chris Brown, an Emory History PhD student studying sport in the Brazilian Amazon, organized the conference with support from Dr. Jeff Lesser of the Emory History Department and Dr. Raanan Rein, Vice President of Tel Aviv University. Several Football Scholars Forum members shared their work and ideas, including keynote speaker, Brenda Elsey, as well as Rwany Sibaja and Ingrid Bolívar.

The video of Alex Galarza’s presentation on the Ciudad Deportiva reveals the intertwining of sport, politics, and society in postwar Buenos Aires. The Ciudad was profoundly shaped by the idea that popular consumption of fútbol and leisure were integral components of citizenship and national progress. This helps explain why Argentina’s national government and Buenos Aires’ municipal authorities subsidized the project and integrated it into the city’s master plan. The general public, not just Boca supporters, invested an impressive amount of money and faith into the undertaking. While the initial success of the Ciudad speaks to the changing ways in which porteños viewed modernity and consumed leisure, the project’s monumental failure in the long run sheds new light on the nature of political and economic change in Argentina after Perón.

Watch this great 20-minute documentary film on the tension and violence that accompanied the memorable Algeria-Egypt 2010 World Cup qualifiers.

Lots of rare footage captures the perspectives and experiences of the Algerian players and officials in both Cairo and Khartoum. Watch as the mainly France-based Les Fennecs players channel fear, insecurity, and rage into a memorable playoff victory and World Cup qualification. The scenes of joyous celebration among the traveling fans and players in Sudan, as well as the partying in the streets of Algiers are something to behold.

The film provides glimpses of both sides of the fútbol-nationalism coin. On the one hand, the Egyptian hooligans’ love of country expresses itself through hatred of the Algerian “other” and spills over into the vicious attacks on the visiting team’s bus depicted in the film. On the other hand, the Algerians’ patriotic unity propels them to victory against their rivals. Raw and riveting stuff.

Thanks to Mezahi Maher (@MezahiMaher) for the English subtitles!

[WATCH: http://vimeo.com/76755353]

Doctor Socrates was futebol’s version of Che Guevara. The fifth and final episode of the superb “Football Rebels” film showcases the lanky, visionary midfielder’s role in the Corinthians Democracy movement that helped push for democratic change in Brazil under military rule in the early 1980s. “One person, one vote,” became the rallying cry of a campaign to elect a sociologist as chairman of Sao Paulo’s popular club. Contesting the election was a conservative businessman who came to embody the forces propping up the military dictatorship. Wearing a headband adorned with the words “Freedom and Justice” Socrates merged football with politics.

As his teammate Wladimir eloquently shows in the film, “Corinthians Democracy” transcended Socrates. The slogan was emblazoned on team jerseys and came to symbolize Brazilians’ dream of universal suffrage. On the final day of the 1983 season, Socrates and his teammates walked on to the pitch carrying a huge banner that read: “Win or lose, but always democracy.” Boosted by this remarkable movement started by courageous, idealistic athletes and embraced by thousands of ordinary men, women, and children, opponents of the dictatorship won provincial elections across the country and strengthened calls for direct presidential elections in Brazil. Watch. Listen. Learn.

Read my post on Socrates’s death here.

Before Pinochet’s rise to power in the September 11, 1973, coup, football clubs sustained a vigorously democratic culture, writes historian Brenda Elsey in her brilliant book Citizen and Sportsmen: Fútbol and Politics in 20th-Century Chile. Colo-Colo and Chile national team forward Carlos Caszely embodies this story. He is at the heart of episode 4 of the “Football Rebels” series on Al Jazeera (iOS users watch it here).

Brought up in a left-wing family in Santiago with its fair share of Communists, Caszely was not your typical professional footballer. He was active in the Players’ Union while many professionals saw themselves as “apolitical,” chiefly concerned with maintaining the status quo. Caszely was well known for his vocal support of Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government: “Since I had use of my own reason,” he said, “I have liked the Left and I am not thinking of changing my ideals,” (Elsey, p. 217).

Interestingly, two months to the day after the coup, Caszely participated in what may well be the strangest match in football history. He took the field for Chile at the National Stadium in a World Cup qualifier against the Soviet Union. But the opponents were not there. Defying FIFA, the Soviets had refused to play in a stadium where more than 12,000 people had recently been imprisoned, tortured, raped, and brutalized by Pinochet’s goons. Caszely played that day because he was scared for his family’s safety. Sadly, this fear was borne out by the regime’s assault on his mother, whose direct testimony provides a dramatic highpoint in the film. As the footballer says: “I said no to dictatorship on every level: no to dictatorship, no to torture . . . So they made me pay for that with what they did to my mother.”

Caszely would go on to score 29 goals in 49 matches for Chile, taking part in both the 1974 and 1982 World Cup finals. He spent five years in Spain (1973-78) before returning to Colo-Colo. In the twilight of his career, Caszely also played for the New York Cosmos (1984) and for Ecuador’s most decorated club, Barcelona SC of Guayaquil. “Ever since I was a little boy and I started walking, holding my father’s hand, in the district where people play against a wall, against a tree, against a mound, against a big stone, against your opponent, with a football, a plastic ball, a rag ball, a paper ball, even a tin can, if there’s nothing else . . .” he always found a way to play. Despite the regime’s repression and intimidation, Caszely’s conscience and his passion for the game could not be silenced. El pueblo unido jamas serà vencido!