Guest Post by Khaya Sibeko (@KhayaSibeko1)

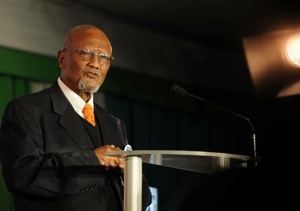

JOHANNESBURG—On October 30, 2013, Leepile Taunyane, South Africa’s legendary football administrator, died at the age of 85. It would not be an exaggeration to compare his passing to the burning of a national archive.

Born in Alexandra, Johannesburg, Taunyane grew up playing football in the streets and then joined Rangers in the early 1950s, a club known for its technical prowess and feared for its lineup stacked with ex-convicts. After hanging up his boots, in the 1960s Taunyane started a career as a football organizer and served as principal first at Alexandra High School and then at Katlehong High.

His administrative career saw him involved in every major transformation in the South African game. Taunyane worked with Bethuel Morolo at the South African Bantu Football Association and then with his successor, George Thabe. In the mid-1980s, an era of massive political and social upheaval in apartheid South Africa, Taunyane led the Transvaal affiliate of Thabe’s Africans-only organization to throw its weight behind the National Soccer League. A precursor of today’s Premier Soccer League, the NSL was a new, racially integrated league launched in 1985 as a break away league from Thabe’s NPSL. Taunyane became the NSL’s first president.

In a recent City Press article, Premier Soccer League and Orlando Pirates chairperson, Irvin Khoza honored his mentor: “I was his student when he was a teacher. He recruited me at the tender age of 14 to become a member of the Alexandra Football Association. We later rubbed shoulders in the national league and federation structures. Dr. Taunyane personifies the values that govern my decision-making and actions, consciously and unconsciously.”

Taunyane was “the last of the Mohicans” of football administrators of a venerable generation. Even when others around him found the temptations of post-isolation football too much to resist, Taunyane remained a diligent and incorruptible servant of the beautiful game. It was no surprise when, a few years ago, the PSL bestowed the honorific title of Life President.

It is not enough to celebrate and award titles, of course. By publicly recognizing Taunyane’s great legacy, local football administrators should strive to follow his exemplary managerial conduct. That would be the best way to remember and honor a “son of the soil” who spared neither time nor energy in the service of football and education.

Undoubtedly, the gods of South African football have placed Taunyane alongside Bethuel Mokgosinyane, Solomon Senaoane, Dan Twala, Albert Luthuli, Henry Ngwenya, George Singh and so many elders of the distant past, men whose efforts shaped our football in the era of segregation and apartheid. Without the contributions of men like Taunyane, South Africa would never have hosted the 2010 World Cup and the PSL would not be among the ten richest leagues in the world.

Guest Post by *Liz Timbs

In Zulu culture, an imbiza is a large ceramic pot used for brewing utshwala (sorghum beer). This vessel enables the fermentation of a fluid that facilitates communication with the amadlozi (ancestors) and lubricates social interactions. Taking my cue from this vernacular technology, I am launching Imbiza: A Digital Repository of 2010 World Cup Stadiums and Fan Parks—an open access collection of primary sources for brewing ideas and encouraging public dialogue about this defining event in South Africa after apartheid.

The potential for this digital project crystallized during a recent session of the Football Scholars Forum on Alegi and Bolsmann’s new book Africa’s World Cup: Critical Reflections on Play, Patriotism, Spectatorship, and Space. During the online discussion, the conversation turned to ways of integrating academically-oriented essays like those in Africa’s World Cup with web-based images, videos, and texts produced by non-specialists for a general audience.

While this idea was initially framed in terms of what could be done for next year’s World Cup in Brazil, the historian in me started thinking about how a project like this could help further understand the 2010 World Cup. Serendipitously, I was also searching for a suitably interesting project to fulfill the requirements of my Cultural Heritage Informatics Fellowship, a program run by Dr. Ethan Watrall at Michigan State University in collaboration with MATRIX, the digital humanities and social sciences center. After some more pondering and a chat with Peter Alegi, my PhD supervisor (and curator of this blog), I decided to go for it.

In building the Imbiza repository, I aim to integrate openly accessible texts, images, sounds, and videos that capture fans’ perspectives and experiences at World Cup stadiums and fan parks. I’ve already begun to collect materials, so accumulating enough sources surely will not be an issue. Among the main challenges for the project will be organizing, tagging, and presenting the items in an accessible, informed, and compelling manner. My hope is that this project will build a model that can be replicated in the study of future World Cups and mega-events, allowing for critical engagement as well as nostalgic reflection.

I do not want this to be a solitary academic venture; that would get away from the whole point of it. I want Imbiza to stand as a testament to the potential of digital technologies for collaborative knowledge production. I am limited by geography, time, and finances in building this archive from my base in East Lansing, but digital platforms, like this one, can get around some of these obstacles.

So consider this blog post a call; a call for submissions, ideas, and inspiration to make Imbiza a success. With the 2014 World Cup in Brazil just a few months away, the time is now to reflect on the legacies of the 2010 World Cup. Ke nako!

—

Follow this project’s progress on Twitter via the hashtag #Imbiza and on the project blog. If you have comments, submissions, sources, or questions, please contact me at imbizaarchive AT gmail.com.

*Liz Timbs is a PhD student in African history at Michigan State University. Her research interests are in the history of health and healing in South Africa; masculinity studies; and comparative studies between South Africa and the United States. Follow her on Twitter: @tizlimbs.

Punk Football for the Working Class

We play therefore we are.

That, in essence, is the sentiment that motivated a group of disaffected Red Devils’ fans opposed to Malcolm Glazer’s $1.5 billion takeover in 2003 of Manchester United to quit Old Trafford and form a new club: FC United of Manchester.

Punk Football, a terrific and profoundly humanistic new documentary film, chronicles FC United’s dramatic 2012-13 campaign which brought them to the brink of promotion to the North Conference League—five levels below the glitz and glamor of the English Premier League.

We are introduced to FC United supporters, officials, players, and coaches who explain what it means to be a community football club owned and democratically run by 2825 co-owners, each holding one voting share. FC United’s manifesto makes it clear this is football by the people, for the people. Football for the working class. “FC United seeks to change the way that football is owned and run, putting supporters at the heart of everything,” states the club’s website. “It aims to show, by example, how this can work in practice by creating a sustainable, successful, fan-owned, democratic football club that creates real and lasting benefits to its members and local communities.”

Around the time of the film’s release, construction began on FC United’s new 5,000-capacity stadium. After wandering for years playing home matches at rented grounds, most recently at Gigg Lane in Bury, members raised more than £2m through a share scheme, and secured additional funding from Sport England, the Football Foundation, the City of Manchester, and Manchester College. (Click here for a recent news story about the stadium.)

The extraordinary story of FC United putting people and poetry before profits is beautifully told in this brilliant documentary. Don’t miss it!

The Football Scholars Forum, an online fútbol think tank I co-founded at Michigan State University, recently launched its 2013-14 season. On October 24, FSF held a lively discussion of Africa’s World Cup: Critical Reflections on Play, Patriotism, Spectatorship, and Space, a newly published collection I edited with Dr. Chris Bolsmann, a South African sociologist based in the UK.

The 90-minute event opened with a consideration of the book’s attempt at blending scholarly and journalistic approaches to exploring the game and its broader implications. The editors and several chapter authors in attendance talked about the process of writing and editing, as well as their experience working with an academic press on a topic with potentially broad appeal.

The book, much of it written in the first person as a loving critique of the 2010 tournament, demonstrates how the FIFA World Cup story is entangled in a web of national and international politics, sporting culture, and global capitalism. Many interventions linked South Africa 2010 to Brazil 2014, particularly through the public financing of expensive and unsustainable new World Cup stadiums in countries with dysfunctional schools and hospitals and high rates of poverty and inequality. The online conversation also featured Luis Suarez’s handball against Ghana and the contradictory legacies of this “African” World Cup.

Participants logged in from half a dozen countries in North America, South America, Africa, and Europe. In attendance: Andrew Guest, Chris Bolsmann

, Christoph Wagner

, David Patrick Lane,

David Roberts,

Derek Catsam,

Jacqueline Mubanga,

Raj Raman,

Orli Bass

, Rwany Sibaja,

Laurent Dubois

, Achille Mbembe

, Jordan Pearson, Sean Jacobs, and Alex Galarza (all via Skype); and Liz Timbs,

Dave Glovsky,

Alejandro Gonzalez, and

Peter Alegi (in East Lansing).

For a Storify Twitter timeline of the event click here.

The audio recording of the discussion is freely available here.

The next Football Scholars Forum event on November 14 will focus on Soccer in the Middle East, a special issue of the journal Soccer and Society (2012), edited by Alon Raab and Issam Khalidi.

Boca Júniors’ “Fraud of the Century”

On October 3-4, Alex Galarza spoke at the Rethinking Sports in the Americas conference at Emory University about the history of Club Atlético Boca Júniors’ Ciudad Deportiva (“sports city”), a gargantuan urban project hailed in the 1960s as a harbinger of national progress and modernization that later became known as the “fraud of the century.” Galarza is a doctoral student in history at Michigan State University and co-founder of the Football Scholars Forum. This paper is part of ongoing doctoral research funded by the Fulbright Program and a FIFA Havelange Scholarship.

The scholarly gathering in Atlanta provided ten early career scholars and graduate students with a chance to present new research papers and receive feedback from peers and senior scholars. Participants read and commented on pre-circulated papers, which made for lively and engaging discussions. Chris Brown, an Emory History PhD student studying sport in the Brazilian Amazon, organized the conference with support from Dr. Jeff Lesser of the Emory History Department and Dr. Raanan Rein, Vice President of Tel Aviv University. Several Football Scholars Forum members shared their work and ideas, including keynote speaker, Brenda Elsey, as well as Rwany Sibaja and Ingrid Bolívar.

The video of Alex Galarza’s presentation on the Ciudad Deportiva reveals the intertwining of sport, politics, and society in postwar Buenos Aires. The Ciudad was profoundly shaped by the idea that popular consumption of fútbol and leisure were integral components of citizenship and national progress. This helps explain why Argentina’s national government and Buenos Aires’ municipal authorities subsidized the project and integrated it into the city’s master plan. The general public, not just Boca supporters, invested an impressive amount of money and faith into the undertaking. While the initial success of the Ciudad speaks to the changing ways in which porteños viewed modernity and consumed leisure, the project’s monumental failure in the long run sheds new light on the nature of political and economic change in Argentina after Perón.

Guest Post by *Hikabwa D. Chipande (@HikabwaChipande)

LUSAKA––The Football Association of Zambia and Hervé Renard have parted company after the 2012 African Nations Cup winning coach signed with French Ligue 1 club Sochaux. FAZ communications officer Eric Mwanza made the announcement on Monday (October 7) after much speculation that the Frenchman was on his way out. Rumors had been flying around Lusaka that the Frenchman was interviewing for jobs overseas. He had also hinted a few months ago before the Zambia vs Ghana 2014 World Cup qualifier that if the team were to fail to make it to Brazil then he’d resign.

LUSAKA––The Football Association of Zambia and Hervé Renard have parted company after the 2012 African Nations Cup winning coach signed with French Ligue 1 club Sochaux. FAZ communications officer Eric Mwanza made the announcement on Monday (October 7) after much speculation that the Frenchman was on his way out. Rumors had been flying around Lusaka that the Frenchman was interviewing for jobs overseas. He had also hinted a few months ago before the Zambia vs Ghana 2014 World Cup qualifier that if the team were to fail to make it to Brazil then he’d resign.

Although FAZ indicated it consulted with Renard and “agreed not to stand in his way,” many Zambians have received this decision with mixed feelings. Some wondered whether Renard had just managed to sweet-talk and dump the national team as he did in an earlier stint with Chipolopolo (copper bullets).

In 2008, Renard landed the Chipolopolo job after working as an assistant to his fellow Frenchman and mentor Claude Leroy, then head coach of the Ghanaian national team, the Black Stars. Renard led Chipolopolo to the quarterfinal of the 2010 African Cup of Nations, a result last achieved at the 1996 tournament in South Africa. In 2010, he left Chipolopolo for better paying Angola, but was soon fired after going four games without a win. After Angola, Renard moved on to coaching USM Alger.

Following the dismissal of Italian coach Dario Bonetti, the Football Association of Zambia announced on October 22, 2011, that Renard would return as coach of the national team on a one-year contract. Peter Makembo, patron of the Zambia Soccer Fans Association, seemed to speak for many local fans when he questioned the loyalty of the French manager. After hearing that Renard was being interviewed at FC Sochaux a few weeks ago, Makembo told Radio Ichengelo that, “as soccer fans we feel betrayed by Renard’s actions.”

However, Renard silenced all his critics in his second tenure at the helm of Chipolopolo by winning the 2012 African Nations Cup: Zambia’s first-ever continental crown. His charges dispatched favourites Senegal in the group stages and African powerhouses Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire in the semi-final and final respectively.

There is no doubt that Renard will remain one of the most respected and loved coaches in the history of Zambian football because of the African title he brought to the country. But some critics point out that he only came back when it suited him and that he reaped where he did not sow since Bonetti, whom he replaced, had done the groundwork for Chipolopolo’s success.

Other Zambians remarked that Renard came here as an inexperienced player and used Zambia to build his coaching resumè before leaving for greener pastures. This is a common phenomenon not only in African sport, but in donor-funded development projects too. Typically, “Western” volunteers arrive, are mentored by local men and women, and then return to their countries where they often become “experts” paid to supervise the Africans who originally taught them much of what they know.

The question remains: is there anything wrong in a European professional coming to an African country like Zambia to build his profile only to leave for a more prestigious, high-paying job? From my point of view, this is how things are and there is little we can do apart from getting used to it. We also need to be realistic and come to terms with the fact that inexperienced, ambitious coaches like Hervé Renard are what poorer countries like Zambia can attract and afford to pay. Few African nations can hire exaggeratedly expensive coaches like the Brazilian Carlos Alberto Parreira, as South Africa did for the 2010 World Cup. (Interestingly, South Africa became the first host nation in World Cup history to be eliminated in the first round of the competition.)

From 2010 to 2013, Renard proved that he is a good coach by delivering what all previous Zambian skippers failed to do: win the African Nations Cup. Many Zambians argue that he is the best foreign coach Zambia has ever had, sometimes in tandem with Yugoslav Ante Buselic who took Chipolopolo to second place in the 1974 Nations Cup in Egypt. Without question, Renard will remain close to the hearts of millions of Zambian soccer fans for a very long time.

However, the Frenchman’s failure to defend the African title and Chipolopolo’s premature elimination from the 2014 World Cup qualifiers compelled FAZ to part ways with Renard. Luckily for Zambia, Renard’s new employers rejected his proposal of bringing his assistant Patrice Beaumelle, also French, to Sochaux. As a result, Beaumelle was chosen as interim head coach of the national team.

Depending on how the new Frenchman will command the Chipolopolo during the friendly match against Brazil in China in a few days’ time, he is likely to be confirmed as Renard’s permanent replacement. Zambians hope that Beaumelle will perform the same miracle as his predecessor, even if he’s only here to strengthen his coaching pedigree before moving on to the next level of world football.

—

Hikabwa D. Chipande is a PhD student at Michigan State University. He is currently in Lusaka conducting archival research and oral history interviews for a doctoral dissertation on the social, cultural, and political history of football in colonial and postcolonial Zambia. Follow him on Twitter: @HikabwaChipande

Fandom, Mzansi-style

Guest Post by *Liz Timbs

In eMpangeni, a small city of 110,000 people in the sugar-producing area of Zululand, South Africa, my host family, the Khuzwayos, seemed typical of the local football fans I had read and heard so much about before arriving for two months of isiZulu language training. Both my “brothers,” Lindane and Njabulo, played soccer and supported PSL Champions Kaizer Chiefs. Lindane, however, also admitted to being a big Cristiano Ronaldo fan.

When I left eMpangeni for Durban (pop. 3+ million!), I found similar loyalties in my new host family, the Nenes. My brother, Ntuthuko, and my sister’s boyfriend, Mthembeni, were both diehard supporters of Kaizer Chiefs, so I “had to” fall in line with them. I was so proud when I finally bought my amaKhosi jersey, but my sister, Noxolo, was horrified; she emphatically told me that she wouldn’t go out with me in public if I was wearing it . . . but that’s a story for another time.

My other sister, Nothando, is an athlete in her own right, so we spoke often about sports. One evening I started asking her about football and was struck by her statement that she preferred watching European matches, especially La Liga contests, a lot more than the South African PSL, let alone Bafana Bafana, the country’s struggling national team. I must have looked completely shocked when she said this, because Nothando started laughing at me (a fairly common occurrence, to be honest) and then went on to explain that European teams’ play was tighter and more professional than that of South African sides.

“They jika too much, those guys,” Nothando declared. In isiZulu, the verb ukujika literally means “to turn,” but the term has also become shorthand for showboating on the football pitch. South African players, in her opinion, cared far more about showing off than about playing clean, controlled football, so she liked to watch world-class teams like Barcelona and Real Madrid instead.

When I went to Pietermaritzburg, the provincial capital of KwaZulu-Natal, to spend time with Izichwe Football Club, I decided to make it a point to ask the players which teams they supported in order to see if Nothando’s opinions would be echoed by other teenagers.

In one of my first interviews, taking care not to ask about a South African team specifically, Asanda told me that he supported Chelsea. He gave a careful, detailed response about their playing style and the specific reasons why he supported the Blues. When I asked him if he had a favorite South African team, his response was less enthusiastic: “I wouldn’t say there is one, but I prefer Orlando Pirates.” Looking back now, I wish I had pushed him on the reasons why, but I had caught him during one of his school breaks and time was short.

When I spoke to the other players on the team, I got largely the same reaction. They would first respond with their favorite European clubs (e.g. Barcelona, Arsenal, Manchester United), then almost as an afterthought they named a South African team, usually Kaizer Chiefs or Orlando Pirates. (One boy was partial to Mamelodi Sundowns, while none supported Maritzburg United).

So what does this tell us about the nature of fandom in South Africa? Maybe nothing terribly revealing given the fairly small sample that I’m pulling from. But taken with the other “evidence” that I gathered over two months it suggests that South African fans have multiple allegiances.

At the Amazulu-Manchester City “Mandela Day” match at Mabhida Stadium, I saw exponentially more people wearing the colors of Manchester United than AmaZulu green. In the market stall where I bought my Chiefs and Bafana Bafana jerseys, there were far more European soccer jerseys available than South African ones.

It seems that the trend is to support European teams first, then the local South African teams. Is this just because of the quality of play, as Nothando Nene told me? Or is it about the accessibility of televised games and the incessant marketing of Messi, Ronaldo, and other global mega stars? Is sport ushering in a new form of colonialism or is there more going on here than meets the eye?

–

*Liz Timbs is a PhD student in African history at Michigan State University. Her research interests are in the history of health and healing in South Africa; masculinity studies; and comparative studies between South Africa and the United States. Follow her on Twitter: @tizlimbs