Next month the University of Johannesburg is hosting an exciting “Research Forum on South African Football.” Organized by the UJ Department of Sport and Movement Studies, the gathering will consider three papers that address socio-historical, sociological, and developmental aspects of football in South Africa, as well as broader issues related to the local game.

In his paper “Professional Football in Apartheid South Africa: Leisure, Consumption and Identity in the National Football League, 1959-1977,” sociologist Chris Bolsmann (Aston University) will present a preliminary analysis of the NFL, a “whites-only” league established in 1959 by a group of (white) Johannesburg businessmen. Playing in segregated stadiums, the NFL introduced professional football to South Africa. At the height of its popularity, it had two divisions, attracted significant corporate sponsorship, and recruited prominent foreign players, such as George Best and Bobby Charlton. The NFL became the leisure and sporting entertainment of choice for significant numbers of black and white South Africans and was unparalleled in popularity during this period.

Ethnographer Marc Fletcher (Department of Sociology, University of Johannesburg) will explore contemporary dynamics in a paper titled “Divisions, Difference and Encounters in Johannesburg Soccer Fandom.” This ethnography of Kaizer Chiefs, Bidvest Wits, and Manchester United supporters’ clubs in the city shows how supporters on the margins of these groups began to engage with the other, crossed racial and class divisions, and thus reinterpreted their understanding of soccer fandom and their wider experiences of everyday life in the city.

Last but not least, Chris Fortuin (Department of Sport and Movement Studies, University of Johannesburg) will discuss “Youth Football Development in South Africa.” The paper notes how in South Africa there is a severe lack of focus on youth football development to sustain national junior and senior teams. I also highlights that youth football development is not coordinated, there is limited success in nurturing young players for the international market, and coach development with a specific focus on youth football is strongly lacking.

This forum takes place on April 19, 2013, 10:00-12:00 at the University of Johannesburg’s Protea Auditorium, School of Hospitality and Tourism, Bunting Road Campus, Auckland Park. For more details please contact Dr. Chris Bolsmann (chris [dot] bolsmann [AT] aston [dot] ac [dot] uk or @ChrisBolsmann on Twitter).

Drogba: The Peacemaker

Omdurman, Sudan, October 8, 2005: moments after Ivory Coast secured qualification to the World Cup finals for the first time, Didier Drogba extemporaneously transformed himself into a peacemaker. His country at the time was torn apart by a civil war between the Muslim-dominated rebel-held north and the mainly Christian south controlled by President Laurent Gbagbo’s government. Surrounded by joyous teammates in the dressing room, Drogba took the microphone and knelt in front of the television cameras. “We have proved that all Ivorians can live together,” he said, “and we can unite with the same objectives. Please, put down your weapons!”

The dressing room scene provides the emotional spark and narrative hook in “Didier Drogba and the Ivorian Civil War,” the riveting first episode of “Football Rebels,” a five-part documentary that began this week on Al Jazeera English. (Watch it here.) “It was just something I did instinctively,” the Ivorian striker would later tell Alex Hayes of The Telegraph in a 2007 interview. “All the players hated what was happening to our country, and reaching the World Cup was the perfect emotional wave on which to ride.”

The Al Jazeera documentary film reveals the little-known story of how Drogba played a key role in getting the national team, The Elephants, to play a 2008 African Nations Cup qualifier against Madagascar in Bouaké in the rebel heartland. Ivory Coast won 3-0, triggering a much needed sense of patriotic pride, national unity, and peace. (Highlights below.)

Presented by former Manchester United star Eric Cantona, “Football Rebels” focuses on players “whose social conscience led them to use their fame and influence to challenge unjust regimes, join opposition movements and lead the fight for democracy and human rights in their countries.” The next episode features another brilliant African player: Rachid Mekhloufi, who left the 1958 French World Cup team to join the FLN team aiding the cause of Algerian independence.

Orlando Pirates: The End of an Era?

Maluti FET College 4, Orlando Pirates 1. Dropped jaws and head-scratching abounded in South Africa last weekend after a third-tier side thumped the reigning league champions in the Nedbank Cup. Stunning results like this are what makes knockout competitions hugely attractive. It’s football’s David vs. Goliath narrative: a humble amateur side from an unknown backwater of the country upstaging their well-heeled city slicker brethren. Does Pirates’ stunning defeat against Maluti signal the end of an era for the fabled Soweto team?

The Buccaneers have been enjoying a purple patch for the past two seasons. An eight-year cup drought ended in 2010/11 when Dutch coach Ruud Krol guided Pirates to a three-cup haul as they annexed the MTN 8, Nedbank Cup and the league title. Krol’s success at Pirates came only after three years of perseverance. In his first season, Pirates lost the title to Supersport United on goal difference and then narrowly lost the Telkom Knockout Cup final to Ajax Cape Town. The following season the going got harder for Krol. Pirates fared badly in the knockout competitions and finished fifth in the league.

A classy defender in his heyday, Krol turned defence into a trademark of his years at Pirates. The side conceded a miserly 22, 18, and 23 goals, but also struggled up front with 37, 26, and 41 goals per campaign. Simply not good enough. The signing of Benni McCarthy (despite his advanced age and injury-prone body) dramatically improved Pirates’ attack. But at the end of a stellar season, the formerly underachieving club did not renew Krol’s contract.

In came Julio Leal. He won two trophies, but halfway through the campaign the Brazilian was booted out, his exit apparently engineered by players unhappy with his coaching methods. Head of Development, Augusto Palacios, took over the reins, steering the Bucs to a second consecutive PSL league title and treble. There would be no continuity in 2012/13, however, as Palacios made an early exit after Pirates got knocked out of the MTN 8 and then lost badly to rivals Moroka Swallows in a league match. Roger De Sa was put in charge.

Pirates’ shocking loss to the minnows of Maluti was by all accounts a major upset. The subsequent league loss to Moroka Swallows (again!) piled even more pressure on De Sa and the Bucs. Two losses in a row, however, do not constitute a crisis. It is a bad spell, a passage any team goes through in the course of a season. Pirates remain in contention for both the league title and the African Champions League. If Pirates were to win both competitions the foibles of the past few weeks would quickly be forgotten by their devoted fans, aka The Ghost. However, if such results don’t materialize, Roger De Sa will almost inevitably become the fall guy, accused of “destroying a great side.”

Truth be told, Pirates management should shoulder the blame for any such negative outcome. De Sa seems like an astute coach and for all the experience he has gained over the years, managing Pirates is his first stern challenge. But will he be given the time to build? After all, he answers to a management team that hired him as the 35th coach in 23 years. Pirates may live to rue dissembling the successful project Krol painstakingly built over the course of three years. If De Sa “fails” then an era will have ended. Humiliating losses like the one to Maluti FET College suggest that Pirates will probably continue to hire and fire many more coaches rather than repeat Krol’s recipe for success.

Rethinking American Soccer History

The Football Scholars Forum, an online fútbol think tank, met on February 26, 2013, for a lively session on the history of American soccer. Steven Apostolov shared a paper on Massachusetts; Gabe Logan on Chicago; and Tom McCabe on northern New Jersey. David Kilpatrick, official historian of the New York Cosmos, moderated the 90-minute conversation.

The Football Scholars Forum, an online fútbol think tank, met on February 26, 2013, for a lively session on the history of American soccer. Steven Apostolov shared a paper on Massachusetts; Gabe Logan on Chicago; and Tom McCabe on northern New Jersey. David Kilpatrick, official historian of the New York Cosmos, moderated the 90-minute conversation.

Listen to the audio from the session here.

Twitter timeline here.

In this video, Alex Galarza and I discuss digital fútbol scholarship at Michigan State University. The conversation ranges from Galarza’s doctoral dissertation entitled “Between Civic Association and Mass Consumption: The Soccer Clubs of Buenos Aires,” to the Football Scholars Forum, the online football think tank.

For more information about Galarza’s research click here.

Photo courtesy of Chris Bolsmann

The Big Boss Man of Nigeria’s Super Eagles, Stephen Keshi, transformed perennial underachievers of the African game into continental champions in the recent African Nations Cup in South Africa.

Keshi weeded out huge egos. He selected players based on ability, merit, and, most important, attitude. He imposed strict curfews on a team brimming with young players of limited experience drawn from Nigerian clubs rather than European ones. Thanks to his steady leadership, the Super Eagles defied the prognostications of pundits and fans alike in claiming their third African title.

Keshi knows how to win. He wore the captain’s armband in Nigeria’s previous Nations Cup triumph in 1994 against Zambia. The captain of the opposing side in that final in Tunis was Kalusha Bwalya, who played an important role in masterminding Chipolopolo’s 2012 championship run. “King Kalu,” currently Zambian Football Association president, saw to it that the nucleus of that winning Chipolopolo side stuck together for more than five years. Big Boss Keshi, on the other hand, overcame a perennial African problem by selecting a team based on what they can do, and what they are willing to do for the collective, instead of which European team they play for. In orchestrating their respective countries’ African triumphs, Bwalya and Keshi merely implemented a philosophy rarely found in most parts of African football: common sense.

The enduring lesson from Nigeria’s 2013 Nations Cup victory is that having so-called big names in your team is less than important than unity and a desire to win. As I have argued before, it is this generation of African football luminaries that must ensure that our football realizes its potential. When Keshi quit his job immediately after winning the title he cast light on the mediocrity of Nigerian football administration. (His resignation has since been withdrawn. Click here and here for more details.) The sight of South African Football Association president Kirsten Nemantandani looking bamboozled, insipid, and nervous when tasked with ceremoniously passing the CAF flag to Issa Hayatou is another reminder of why African football management should be the prerogative of competent, visionary people; not motley crews of myopic sorts whose organizations find themselves in the midst of FIFA match-fixing investigations.

Witnessing Slim Jedidi’s farcical refereeing in the Ghana-Burkina Faso semifinal, a fellow brother of mine noted: “Success in Africa is never rewarded because merit is hated. Why? Because the Big Men are there by fraud and manipulation.” Thank you to runners-up Burkina Faso and to Stephen Keshi for demonstrating how African football can soar above the deeds of those who always try to bring us backwards. May it continue in that trajectory.

Nigeria’s Triumph, Africa’s Tournament

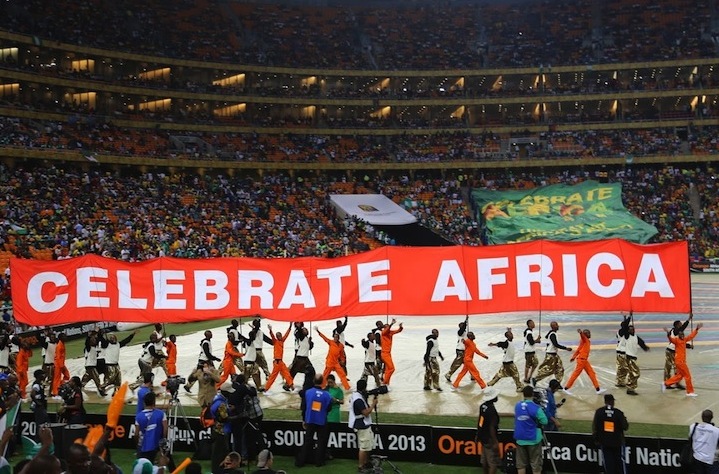

Photos courtesy of Chris Bolsmann

By Chris Bolsmann (@ChrisBolsmann) and Marc Fletcher (@MarcFletcher1)

February 11, 2013 (23rd anniversary of Mandela’s release from prison.)

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA

Chris Bolsmann (CB): In February 1996, I celebrated with 100,000 other delirious South Africans packed into Soccer City after we beat Tunisia in the African Nations Cup final. It was a special victory and an important moment in South African sports history. It was more special that the 1995 rugby World Cup win because the soccer crown was won by a genuinely racially integrated team playing the game obsessively followed by most South Africans. 1996 has remained a very powerful memory for me over the last 17 years. However, there has always been one lingering doubt in the back of my mind: Nigeria, the reigning African champions at the time, did not participate.

The Nigerian junta’s sham trial and execution in November 1995 of author and environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa drew a sharp rebuke from then-South African President Nelson Mandela. Relations between the two countries quickly deteriorated and led to the reigning champions’ withdrawal from the 1996 tournament in South Africa. These events intensified the heated rivalry between South Africa and Nigeria. For Sunday’s final I had planned to support Burkina Faso. The Burkinabé had reached their first-ever Nations Cup final by playing exciting and entertaining football; they were also the under-dogs.

Marc Fletcher (MF): I arrived at Soccer City’s National Stadium almost four hours before Sunday’s kickoff and was pleased to see that the Nations Cup party atmosphere had finally hit Johannesburg. Considering the large Nigerian population in the city, it was unsurprising that the vast majority of the fans streaming in were Super Eagles supporters. More surprising was the significant number of South Africans choosing to support Nigeria. After all, “Nigerians” here are perceived as illegal immigrants and dangerous criminals. Tensions between African immigrant communities and South Africans have sometimes spilled over into xenophobic attacks, as in the deadly riots of 2008. But the Nations Cup final appeared to turn this association upside down; being Nigerian, or identifying with Nigeria, had become a positive thing, if only temporarily.

Walking towards the spectacular stadium, it was also apparent how this experience differed from the World Cup I attended almost three years before. Back then, football fans had been promised an “African” World Cup (whatever that entailed). South Africans and tourists alike had been repeatedly told that “It’s Africa’s Turn” and that South Africa would show the world the positives Africa had to offer. Instead, a bland, commercialised FIFA-controlled environment reduced the local flavour of the tournament to the controversy surrounding vuvuzelas. As one of my local research informants summarised, “this could be anywhere!”

Walking towards the spectacular stadium, it was also apparent how this experience differed from the World Cup I attended almost three years before. Back then, football fans had been promised an “African” World Cup (whatever that entailed). South Africans and tourists alike had been repeatedly told that “It’s Africa’s Turn” and that South Africa would show the world the positives Africa had to offer. Instead, a bland, commercialised FIFA-controlled environment reduced the local flavour of the tournament to the controversy surrounding vuvuzelas. As one of my local research informants summarised, “this could be anywhere!”

But 2013 was different. Cheaper tickets must have been a factor, allowing those who could not attend World Cup matches to engage, to experience and to celebrate. The bland hot dogs of the World Cup had been replaced with the pap and steak and boerwors rolls, staple foods at domestic matches. The relentless drumming from the small group of Burkinabé in the seats near me infused the tournament with the beat that had been lacking nearly three years ago. People of different racial, ethnic, class, and gender backgrounds socialised with one another–a dream for Rainbow Nation proponents–while the vast panoply of different African football shirts and flags reinforced a wider belonging to “Africa.” Security checks on spectators were inconsistent at best. A feeble, half-hearted pat down from a steward would do little to detect things such as flares, which constantly happens at local games (my favourite is still seeing someone pull out a full bottle of whiskey from his sock!). The pitch resembled a beach with players kicking up clouds of sand constantly. When Nigeria went ahead through Sunday Mba’s brilliant goal three-quarters of the stadium erupted in celebration. A far cry from the World Cup.

CB: Our tickets for the final were purchased months in advance, but as we tried to get to our seats it was clear that Nigerian fans occupied this part of the stadium. After stern words and persistence, we finally sat in our seats. It took stadium security and the South African police a good thirty minutes of the first half to move Nigerian fans seated on the stairs next to us to proper seats. I chatted to Sunday, a Nigerian national who told me he currently lives in Germiston on the East Rand (part of greater Johannesburg). Directly behind us was a group of eight or so trumpeters and a couple of drummers who played throughout the match. It was hard not to sway and dance to the fantastic music. By the time Nigeria took the lead my fickle allegiance was swaying towards the Super Eagles. When the final whistle blew I was happy Nigeria had won their third African title and had done so on South African soil. I look forward to Nigeria representing Africa at the Confederations Cup in Brazil later this year. But even more exciting is the prospect of South Africa regaining the lofty heights of 1996 and a show down with Nigeria. Despite Bafana’s quarterfinal exit, I carry on believing.

MF: I’ve fallen into the trap of comparing a westernised, modern, slick, commercialised World Cup with the chaotic yet dynamic African tournament. I’m not sure how to extricate myself from this other than to continue digging my hole with my romanticism of the final. It was a vibrant celebration of African football. Yet, as I drove to work this morning, the newspaper headlines attached to most Jo’burg streetlights were not about the final but Manchester United extending their lead at the top of the English Premier League. Is the 2013 Africa Cup of Nations already being forgotten?

MF: I’ve fallen into the trap of comparing a westernised, modern, slick, commercialised World Cup with the chaotic yet dynamic African tournament. I’m not sure how to extricate myself from this other than to continue digging my hole with my romanticism of the final. It was a vibrant celebration of African football. Yet, as I drove to work this morning, the newspaper headlines attached to most Jo’burg streetlights were not about the final but Manchester United extending their lead at the top of the English Premier League. Is the 2013 Africa Cup of Nations already being forgotten?