The Football Scholars Forum, the online think tank based at Michigan State University, recently explored fascinating aspects of the long and complex relationship between fútbol and politics in the history of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

The Football Scholars Forum, the online think tank based at Michigan State University, recently explored fascinating aspects of the long and complex relationship between fútbol and politics in the history of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

In its second session of the 2015-16 season, FSF co-founder Alex Galarza, PhD candidate in History at Michigan State, shared a chapter from his dissertation: “Dreaming of Sports City: Consumption, Urban Transformation, and Soccer Clubs in Buenos Aires.” Galarza’s doctoral research has been funded by prestigious national and international grants, including the coveted Fulbright and FIFA Havelange scholarships.

The potential impact of Galarza’s dissertation work beyond the ivory tower of academia can be gleaned from his involvement in an ongoing documentary film project. Working with four young Argentine journalists, Galarza aims to use the format of filmmaking to reveal the “hidden” history of Boca Juniors’ Ciudad Deportiva—a (failed) urban renaissance construction project that sheds new light on the role of professional soccer clubs in city planning and everyday life. (Watch the trailer here.)

The Forum encouraged Galarza to explain how this history of Buenos Aires compares with the experiences of other Latin American cities, and broader processes of modernization and state formation. The author and participants also discussed constructions of race, whiteness, and gender through fútbol, the politics of club governance, and the ideological projects behind stadium construction.

Listen to or download the audio recording here.

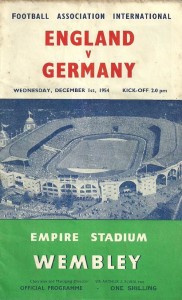

The Football Scholars Forum opened its 2015-16 season on Wednesday, October 14, with a discussion of Christoph Wagner’s DeMontfort University PhD thesis entitled “Crossing The Line: The English Press and Anglo-German Football, 1954-1996.”

The Football Scholars Forum opened its 2015-16 season on Wednesday, October 14, with a discussion of Christoph Wagner’s DeMontfort University PhD thesis entitled “Crossing The Line: The English Press and Anglo-German Football, 1954-1996.”

Based on extensive archival research, “Crossing the Line” analyzes representations of Germany and Germans in English newspapers’ football coverage of key international matches between the two western European nations. Within a shifting post-war historical context, the study notes a persistent undercurrent of hostility in Anglo-German cultural relations, football included.

However, two distinct phases were described. In the first, extending from the 1950s to the rise of Thatcher, dailies generally adopted a restrained tone and their coverage was notable for the “relative absence of anti-German sentiment.” A major transformation occurred in the second phase, from the 1980s to the mid-1990s, as English press coverage turned more negative, chauvinistic, and increasingly xenophobic.

The FSF discussion with the author touched on many different aspects of Wagner’s study, from the militarization of language in the football press and the forging of national stereotypes to narratives of English decline, methodology and sources.

A recording of the session is available here.

For more information about the Football Scholars Forum visit the online think tank’s website.

Liberi Nantes is the first competitive football club in Italy made up almost entirely of refugees and migrants. Playing in the Terza Categoria—the bottom rung of the Italian football pyramid—the team provides a peaceful space for West African men who survive treacherous journeys from West Africa to Libya and then by sea to the island of Lampedusa.

In this excellent short video, published on The Guardian website, we meet some of the players and Alberto Urbinati, a Lazio fan who founded the club several years ago in response to the plague of racism in Italian football and society. The project has taken on added significance today as Italy struggles to cope with the growing refugee crisis.

The Apartheid Football Syndrome

Photo: Durban & District African FA select team, Rhodes Centenary tournament, Salisbury, Rhodesia (1953)

Football is Coming Home is pleased to receive and publish a guest essay by Zipho Dlangalala, a South African fútbologist who has coached players and trained coaches for many years at all levels. He is a teacher by profession. It has been lightly edited for style.

Guest Post by Zipho Dlangalala (makhandaz@hotmail.com)

KWAZULU-NATAL—All sports are played in, and influenced by, past and present social conditions. This is largely, if not entirely, because sport is played by people who are social beings.

When we see most of our South African players playing the same way, looking like identical midfielders, we should know instantly that we are looking at them with “foreign eyes.” They will always look like that as long as we evaluate them with foreign tools and criteria.

To African eyes, it is those midfield players that should reveal the nature and inclination of our players. Their creativity and desire to care for the ball—the uninhibited attraction to artistic modes of play—are great assets that we should have treasured so that their game exhibits the same attributes found in them naturally, at least before being diluted.

Regrettably, the Apartheid philosophy and its legacy was too strong for most of us. Based on seeing life through Master-Slave, Boss-Subordinate, Superior-Inferior, Rich-Poor, Educated-Illiterate, Advanced-Primitive, civilized-uncivilized relationships, this “baaskap” paradigm has engulfed us. Even when we know it is not desirable, we often find ourselves promoting it, advocating on its behalf through actions more than words.

It makes us feel acceptable and progressive to be seen as “the master.” We do everything and anything to feel accepted and to get approval from those who represent “the master” perspective. It has been engraved in us to look for this approval, otherwise we feel we do not have the capacity to stand by ourselves and achieve success on our own. The desire to be associated with, to be affiliated to, approved by, “the master” is hard to resist for most. It is this prevailing mentality in South Africa that undermined indigenous cultures, languages, restricted people’s movement and freedom to associate, to think, to explore, to design, to invent, to discover.

It is a “total control” approach of life. It attempts to control what people think and learn. Given the slightest opportunity, it dictates LIFE to each and every person who is supposed to be subordinated (and limited) to its wishes and desires.

In a cultural and socio-economic environment shaped by a social hierarchy long based on race, fertile ground exists for past tendencies to endure. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Football under these conditions cannot be sustained, let alone developed.

Looking at football through a particular lens inevitably results in the game looking in a particular manner. Are we using proper African perspectives to look at the game as it is in Africa? Are our views coloured to give us a special feeling? Are we ready to bring something new to world football or are we content to follow established paths and continue to consume what is already in the market? We are entrepreneurs and have skills. We need to develop them and show our own ideas to the world. We need to create something new in our football for the world to sit up and take note.

Thieves, rapists and murderers in Uganda’s only maximum security prison play for Manchester United, Arsenal, Chelsea, Barcelona, Juventus, and . . . Hanover 96.

In a gripping podcast recorded in Luzira, a suburb of Kampala, David Goldblatt tells the story of the Upper Prison Soccer Association (UPSA), “the most elaborate prison football league in the world” (listen here).

What emerges form this radio documentary-style piece is a deeply humanistic portrait of a prisoner-run sporting organization that does more, much more than stage occasional kickabouts.

UPSA injects fun, entertainment, and healthy recreation in the otherwise stultifying drudgery of life behind bars. Running it requires hard work, sophisticated organization, and tight discipline. It is a complex, sometimes stressful, affair.

But it works. UPSA helps inmates cope with life on the inside as it strives to transform violent criminals into citizens better prepared for what awaits them after their sentences have been served.

On Tuesday, June 2, Sepp Blatter announced his intention to resign as FIFA president just four days after winning reelection to a fifth term — an electoral victory that simply could not have happened without the support of FIFA’s African members.

According to unofficial calculations, the 133 votes secretly cast for Blatter came from Africa (53), Asia (46), and North America (minus the United States) and the Caribbean (34).

Why did Africans unanimously support the leader of a troubled, even loathed, organization which two days earlier witnessed the arrest of seven of its executives in Zurich on US bribery and corruption charges?

As an academic who has been researching, publishing and teaching the history and culture of African football for two decades, I want to offer a possible answer to this challenging question.

Read full text here at The Conversation.

Thirty years ago, on May 29, 1985, I gathered with a dozen teammates in a living room in Rome to watch the European Cup final between my Juventus and Liverpool. Barely fifteen years old, black-and-white scarf around my neck, there was nothing more I wanted than to avenge our shocking loss to Hamburg in the final two years earlier.

There was reason to be moderately optimistic, partly because four months earlier we had beaten Liverpool 2-0 (Boniek 39′, 79′) to claim the 1984 European Super Cup.

Forty-five minutes or so before the scheduled kickoff in Brussels, I took my seat on the floor. A perfectly unobstructed view of the television screen. Within minutes, disturbing images of chaos at the run down Heysel Stadium started beaming in.

The voice of Bruno Pizzul, a kind of Martin Tyler of Italian football, conveyed bewildering news. Something terrible was unfolding. Death at the stadium? We switched on the radio. Confusion.

Then, slowly, an accumulation of anecdotal reports led to confirmation of an unspeakable tragedy: 36 people were dead (a figure later revised to 39). Almost all Juventus fans. Men, women, and children killed in a stampede and wall collapse in the corner Z sector as they fled a charge by Liverpool supporters.

My heart was in my throat.