This year’s Africa Cup of Nations is underway in Equatorial Guinea. RFI talks about African football and media coverage with Peter Alegi, an authority on the game in Africa and Professor of History at Michigan State University in the United States. [full text here.]

Click below to listen to the interview. (iOS users click here.)

Tag: African Nations Cup

The 2015 African Nations Cup begins on January 17 in Equatorial Guinea. The oil-rich dictatorship, a former Spanish colony with a population of 736,000, agreed to host the tournament on short notice after Morocco pulled out due to fears related to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

Africa’s most important tournament is organized by the Confederation of African Football (CAF), a trailblazing pan-Africanist institution born at the dawn of the era of decolonization. Joining the world body, as I’ve written elsewhere, was an honorable, quick, and inexpensive way for newly independent nations to assert their full membership in the international community.

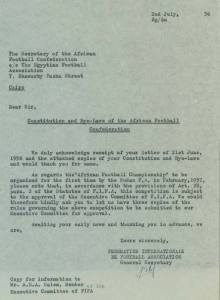

CAF took tangible shape at the 1956 FIFA Congress in Lisbon. There, delegates from Egypt, Sudan, and South Africa convened to draft a constitution and by-laws. The men also decided to organize a continental championship. Ethiopia was also involved in the discussions, but Yidnecatchew Tessema was unable to travel to Lisbon. The African proposal was later sent to FIFA for review and approval (see image at left).

On February 8, 1957, football officials from Sudan, Egypt, Ethiopia, and South Africa convened at Khartoum’s Grand Hotel to formally launch CAF. Fred Fell, a white man representing apartheid South Africa, was invited because his country was a member of FIFA and the Africans did not wish to be perceived as undiplomatic. In the meantime, the white South African football association gingerly debated the composition of the national team. However, the authorities Pretoria opposed a mixed selection and the white football establishment did not challenge the policy.

There are conflicting accounts about what happened next. CAF officials stated that they promptly excluded South Africa in a show of unequivocal pan-African solidarity. Fell and white South African football put forward a different story: they claimed they withdrew the team prior to any sanctions due to the team’s impending tour to Europe as well as security concerns linked to the ongoing Suez Crisis. Unfortunately, the minutes of the meeting at CAF were later destroyed in a fire so we may never know the exact truth of the matter. What is certain is that the South African issue did not disappear. To the contrary, the struggle against apartheid in football would become a powerful bond that united CAF and nearly all African nations for three decades.

South Africa’s absence in 1957 meant that only three teams, comprised of amateurs, participated in the inaugural African Nations Cup. Ethiopia, which had been drawn to play against South Africa, received a bye into the final. Egypt defeated hosts Sudan 2–1 and then dispatched Ethiopia 4–0 in the final watched by a crowd of 30,000 at the Stade Municipal. All four goals were scored by striker Mohammed Diab El-Attar “Ad Diba.” “Those were unforgettable matches,” Ad Diba recalled in an interview in 2001. “The success of this championship and its popularity amongst the Sudanese encouraged the African federation to organize a tournament on a biennial basis and to be played in a different country each time,” he said. Ad Diba made history again eleven years later in Addis Ababa, when he refereed the Afcon final between Congo (DRC) and Ghana (see video).

In those early days, CAF brought to life Kwame Nkrumah’s dream of a United States of Africa. At the same time, football provided a rare form of national culture, unity, and pride in postcolonial Africa.

Today, the African Nations Cup has transformed itself into a globalized commercial event with multinational corporate sponsors, matches on satellite television and online, many European coaches, and most players on the sixteen squads employed by European clubs. It is a far cry from 1957. And yet an alluring contradiction has endured: the Afcon showcases Pan-African solidarity while triggering 90-minute nationalism.

I settled into my seat at Fresh View Cinemas, Levy Park, in Lusaka, for the premiere of “e18hteam”—the first feature film about the history of football in Zambia—with more than a passing interest in the subject.

With generous funding from the FIFA João Havelange Research Scholarship, I have spent the past several years researching and writing the first academic history of football in Zambia as part of my doctoral studies at Michigan State University.

The cinema audience in Lusaka included football administrators, fans, members of the media, and VIPs like Shallot Scott, the wife of Zambia’s Vice President Guy Scott, and Roald Poulsen, the Danish coach who helped rebuild Zambia’s national team after the 1993 Gabon air crash that killed 18 supremely talented players.

The film is a partnership between Zambian producer Ngosa Chungu and Spanish writer, director and producer Juan Rodriguez-Briso. “e18hteam” focuses on Chipolopolo (Copper-bullets), Zambia’s national team. The narrative begins with Zambia’s famous 4-0 destruction of Italy in the 1988 Olympic tournament in South Korea. Then it turns to the tragedy that defined a generation: the 1993 Gabon air crash. The film goes on to explore the rebuilding of a new team, which (almost miraculously) reached the 1994 AFCON final against Nigeria. The narrative arc closes on an uplifting note as it documents the golden generation that won Zambia its first continental crown in 2012 in Libreville, just a few miles from the site of the crash nineteen years earlier.

Spectators went beyond the usual gamesmanship at Sierra Leone’s practice in Yaoundé, Cameroon: chants of “Ebola, Ebola” rained on the visitors. “You feel humiliated, like garbage, and you want to punch someone,” said John Trye, a reserve goalkeeper, speaking to Jeré Longman of The New York Times (click here to read the article).

Two months ago, Sierra Leone had reached number 50 in FIFA’s world ranking–an excellent result for a country ranked 183rd in the Human Development Index. Coached by Johnny McKinstry, an ambitious 29-year-old from Belfast, the team seemed poised to qualify for the 2015 African Nations Cup before the catastrophic Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

The Confederation of African Football decreed that Sierra Leone’s Nations Cup home qualifiers had to be played outside the country. When the team journeyed to Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo, to play a “home” match against the DRC, midfielder Khalifa Jabbie reported that “they treated us like aliens.” In Abidjan, the Ivory Coast players opted for fist-bumps with their opponents instead of shaking hands; fans in the stands taunted the visitors with “Stop Ebola” signs and insulting chants (see photo above).

Already facing stiff competition in a qualifying group that includes Ivory Coast and Cameroon, the itinerant Sierra Leoneans lost matches and became demoralized. “The players tried their very best but sometimes what the mind’s willing to do, the body simply can’t anymore,” said their Irish coach. Making matters worse, a couple of weeks before Sierra Leone’s away match in Cameroon, McKinstry was fired with a curt email from the sports ministry, which then fought publicly with the country’s Football Association over the selection of his successor.

While Sierra Leonans have much more serious matters to deal with than sport, the stigma and fear associated with Ebola is also denying emotional solace to a nation generously endowed with football passion and patriotism. As their new coach, Atto Mensah, put it, “This is the only way we can make people happy. We owe them joy.”

Nigeria’s Triumph, Africa’s Tournament

Photos courtesy of Chris Bolsmann

By Chris Bolsmann (@ChrisBolsmann) and Marc Fletcher (@MarcFletcher1)

February 11, 2013 (23rd anniversary of Mandela’s release from prison.)

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA

Chris Bolsmann (CB): In February 1996, I celebrated with 100,000 other delirious South Africans packed into Soccer City after we beat Tunisia in the African Nations Cup final. It was a special victory and an important moment in South African sports history. It was more special that the 1995 rugby World Cup win because the soccer crown was won by a genuinely racially integrated team playing the game obsessively followed by most South Africans. 1996 has remained a very powerful memory for me over the last 17 years. However, there has always been one lingering doubt in the back of my mind: Nigeria, the reigning African champions at the time, did not participate.

The Nigerian junta’s sham trial and execution in November 1995 of author and environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa drew a sharp rebuke from then-South African President Nelson Mandela. Relations between the two countries quickly deteriorated and led to the reigning champions’ withdrawal from the 1996 tournament in South Africa. These events intensified the heated rivalry between South Africa and Nigeria. For Sunday’s final I had planned to support Burkina Faso. The Burkinabé had reached their first-ever Nations Cup final by playing exciting and entertaining football; they were also the under-dogs.

Marc Fletcher (MF): I arrived at Soccer City’s National Stadium almost four hours before Sunday’s kickoff and was pleased to see that the Nations Cup party atmosphere had finally hit Johannesburg. Considering the large Nigerian population in the city, it was unsurprising that the vast majority of the fans streaming in were Super Eagles supporters. More surprising was the significant number of South Africans choosing to support Nigeria. After all, “Nigerians” here are perceived as illegal immigrants and dangerous criminals. Tensions between African immigrant communities and South Africans have sometimes spilled over into xenophobic attacks, as in the deadly riots of 2008. But the Nations Cup final appeared to turn this association upside down; being Nigerian, or identifying with Nigeria, had become a positive thing, if only temporarily.

Walking towards the spectacular stadium, it was also apparent how this experience differed from the World Cup I attended almost three years before. Back then, football fans had been promised an “African” World Cup (whatever that entailed). South Africans and tourists alike had been repeatedly told that “It’s Africa’s Turn” and that South Africa would show the world the positives Africa had to offer. Instead, a bland, commercialised FIFA-controlled environment reduced the local flavour of the tournament to the controversy surrounding vuvuzelas. As one of my local research informants summarised, “this could be anywhere!”

Walking towards the spectacular stadium, it was also apparent how this experience differed from the World Cup I attended almost three years before. Back then, football fans had been promised an “African” World Cup (whatever that entailed). South Africans and tourists alike had been repeatedly told that “It’s Africa’s Turn” and that South Africa would show the world the positives Africa had to offer. Instead, a bland, commercialised FIFA-controlled environment reduced the local flavour of the tournament to the controversy surrounding vuvuzelas. As one of my local research informants summarised, “this could be anywhere!”

But 2013 was different. Cheaper tickets must have been a factor, allowing those who could not attend World Cup matches to engage, to experience and to celebrate. The bland hot dogs of the World Cup had been replaced with the pap and steak and boerwors rolls, staple foods at domestic matches. The relentless drumming from the small group of Burkinabé in the seats near me infused the tournament with the beat that had been lacking nearly three years ago. People of different racial, ethnic, class, and gender backgrounds socialised with one another–a dream for Rainbow Nation proponents–while the vast panoply of different African football shirts and flags reinforced a wider belonging to “Africa.” Security checks on spectators were inconsistent at best. A feeble, half-hearted pat down from a steward would do little to detect things such as flares, which constantly happens at local games (my favourite is still seeing someone pull out a full bottle of whiskey from his sock!). The pitch resembled a beach with players kicking up clouds of sand constantly. When Nigeria went ahead through Sunday Mba’s brilliant goal three-quarters of the stadium erupted in celebration. A far cry from the World Cup.

CB: Our tickets for the final were purchased months in advance, but as we tried to get to our seats it was clear that Nigerian fans occupied this part of the stadium. After stern words and persistence, we finally sat in our seats. It took stadium security and the South African police a good thirty minutes of the first half to move Nigerian fans seated on the stairs next to us to proper seats. I chatted to Sunday, a Nigerian national who told me he currently lives in Germiston on the East Rand (part of greater Johannesburg). Directly behind us was a group of eight or so trumpeters and a couple of drummers who played throughout the match. It was hard not to sway and dance to the fantastic music. By the time Nigeria took the lead my fickle allegiance was swaying towards the Super Eagles. When the final whistle blew I was happy Nigeria had won their third African title and had done so on South African soil. I look forward to Nigeria representing Africa at the Confederations Cup in Brazil later this year. But even more exciting is the prospect of South Africa regaining the lofty heights of 1996 and a show down with Nigeria. Despite Bafana’s quarterfinal exit, I carry on believing.

MF: I’ve fallen into the trap of comparing a westernised, modern, slick, commercialised World Cup with the chaotic yet dynamic African tournament. I’m not sure how to extricate myself from this other than to continue digging my hole with my romanticism of the final. It was a vibrant celebration of African football. Yet, as I drove to work this morning, the newspaper headlines attached to most Jo’burg streetlights were not about the final but Manchester United extending their lead at the top of the English Premier League. Is the 2013 Africa Cup of Nations already being forgotten?

MF: I’ve fallen into the trap of comparing a westernised, modern, slick, commercialised World Cup with the chaotic yet dynamic African tournament. I’m not sure how to extricate myself from this other than to continue digging my hole with my romanticism of the final. It was a vibrant celebration of African football. Yet, as I drove to work this morning, the newspaper headlines attached to most Jo’burg streetlights were not about the final but Manchester United extending their lead at the top of the English Premier League. Is the 2013 Africa Cup of Nations already being forgotten?

Guest Post by Marc Fletcher* (cross-posted with permission of Africa is a Country and the author.)

One of the key sights of this year’s Africa Cup of Nations has been emptiness. Aside from the opener between South Africa and Cape Verde, the television cameras have picked up images of large swathes of empty seats. Whether it was Burkina Faso’s last gasp equalizer against Nigeria in Nelspruit or Tunisia’s equally late winner versus Algeria in Rustenburg, the empty seats appeared to outnumber the fans that had made the trip. Coverage from previous editions of the tournament in Ghana, Angola and Equatorial Guinea picked up similar images. This is clearly not a South African-only problem.

I had earlier hoped that the more reasonable pricing structure for this tournament as opposed to the 2010 World Cup would have made the games more accessible to majority of poorer, working class football fans; those who make up the vast majority of the support base of South Africa’s domestic clubs. The empty seats suggest that it’s reaching few people in general.

So what are the issues behind this?

Firstly, there aren’t many players in this tournament that can be described as superstars. In the World Cup, there was Messi, Ronaldo and the entire Spanish squad. This time around, there’s Didier Drogba, whose career is winding down in China but few others. Yes, there are players such as Yaya Touré and Asamoah Gyan but they simply do not have the same star status. Why spend hard-earned money to watch two teams that you have little or no interest in?

Secondly, the 5 pm kick off times are hardly conducive to getting bums on seats. As I write this, I have one eye on the Bafana v Angola match. While attendance seems to be significantly greater than in most of the other matches, there are still many empty seats. Traffic at this time in the major cities can be nightmarish and some fans will be unwilling to put themselves through the gridlock and confusion. To make sure that you get to the stadium in plenty of time means taking the afternoon off work.

A big contributory factor is that that there are few, if any African countries that have a large fan base with a large enough disposable income to fly out to the southern tip of the continent for the tournament. Unlike the vast hoards of traveling football tourists at the Euros or at the World Cup, the support of visiting teams is usually restricted to a small rump of die-hard regular fans who are sometimes subsided by the state or political parties. While the commitment on the part of these fans is impressive, this is not going to fill these former World Cup venue. This is a problem that is not going to go away anytime soon.

But the thing that strikes me most as I write from Johannesburg is the absence of evidence that the tournament is taking place. In 2010, there were numerous posters around the city, large fan parks with big screens and people blowing vuvuzelas on street corners. Thousands crammed onto the streets in the north of the city when Bafana went on an open-top bus tour while a giant photo of Cristiano Ronaldo was emblazoned on Nelson Mandela Bridge. This time, it is severely underwhelming. There is no party atmosphere, no fan parks, little hype on local television or radio. Bafana shirts are far less apparent on the street in contrast to 2010. It’s not totally absent though. Staff at my local Spar were wearing their Bafana shirts today, while bar staff on Soweto’s tourist strip on Vilakazi Street were doing the same.

Still, it’s as if the tournament has passed Jo’burg by and I wouldn’t be surprised if it passes most of South Africa by with little more than a passing awareness that Africa’s biggest football tournament is in their country. The slogan of the tournament is “The beat at Africa’s feet,” but this beat is strangely subdued.

Maybe people realize that they have more important things to do than watch football?

N.B. During the South Africa vs Angola match, Moses Mabhida stadium in Durban seemed to be fuller in the second half. The commentator on Supersport (the South African satellite channel that dominates football broadcasting on the continent) has suggested that there is an excessive number of security cordons, which has delayed many fans from getting into the ground until the latter part of the first half.

* Marc Fletcher (MarcFletcher1), a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Johannesburg, blogs at One Man and His Football: Tales of the Global Game.

Guest Post by Elliot Ross (@africasacountry)

1. This high-stakes knockout format might not be so bad after all. Qualifying groups are long, turgid affairs, especially the European ones, international football’s equivalent of the snoozetastic-but-moneyspinning UEFA Champions League group stages. Knockout football puts the big names at risk, as they should be. This past weekend was joyous.

2. Look out for the central African sides. I reckon DR Congo look a good early outside bet (remember current champions Zambia were 50-1 behind Burkina Faso and Libya before the 2012 tournament) and nobody will want to play Central African Republic — Egypt’s conquerors featured in this video — if Les Fauves manage to hold onto their slender 1-0 lead over Burkina Faso.

3. The Sudanese really know how to celebrate a goal. Watching big Sudan-Ethiopia games feels like being back in the 1950s. All we need is Ad-Diba to turn up with his whistle to referee the second leg.

4. Home advantage is everything. Just ask the Moroccans, the Angolans or the Cameroonians. On the flip side, it means all three of those teams will hold out hope of turning their ties around in October. It also means that despite their recent struggles Bafana Bafana can’t be discounted as serious contenders when South Africa host the tournament early next year.

5. Cabo Verde could have a big future in the African game, especially if they can prevent their top players from representing Portugal and other nations.

6. As Jonathan Wilson (@JonaWils) points out, Cote d’Ivoire’s defence looks a bit dodgy. Kolo Toure is seriously slowing down these days and former Dunfermline Athletic stalwart Sol Bamba might be a favourite of Sven Goran Eriksson, but he’s not the most positionally sound. Thankfully, Eboué has been restored by Sabri Lamouchi at the expense of the clunking Gosso. Hopefully, Seydou Doumbia will be next.

7. Papiss Demba Cissé is a genius. As the video above shows, the Senegalese striker scores goals most players wouldn’t dream of attempting.

8. Zambia have to be very careful in their second leg in Kampala. That encounter is going to be tense, and I’ve got a hunch Uganda will do a number on the African champs.

9. I miss Samuel Eto’o. What’s the price for his dramatic return in the second leg? If Eto’o does not show, then Cameroon look doomed. Whatever the internal drama behind this years-long row, it’s a dispute between a handful of soon-to-be-forgotten officials and one of Africa’s greatest footballers ever, and the result is to that a huge chunk of international matches is missing from his career and Cameroon are absolutely hopeless.

10. Remember the name: Christian Atsu. Is he the Ghanaian Messi? We don’t know but he looked tasty against Malawi and Porto’s scouts really know talent when they see it.