Photo: Durban & District African FA select team, Rhodes Centenary tournament, Salisbury, Rhodesia (1953)

Football is Coming Home is pleased to receive and publish a guest essay by Zipho Dlangalala, a South African fútbologist who has coached players and trained coaches for many years at all levels. He is a teacher by profession. It has been lightly edited for style.

Guest Post by Zipho Dlangalala (makhandaz@hotmail.com)

KWAZULU-NATAL—All sports are played in, and influenced by, past and present social conditions. This is largely, if not entirely, because sport is played by people who are social beings.

When we see most of our South African players playing the same way, looking like identical midfielders, we should know instantly that we are looking at them with “foreign eyes.” They will always look like that as long as we evaluate them with foreign tools and criteria.

To African eyes, it is those midfield players that should reveal the nature and inclination of our players. Their creativity and desire to care for the ball—the uninhibited attraction to artistic modes of play—are great assets that we should have treasured so that their game exhibits the same attributes found in them naturally, at least before being diluted.

Regrettably, the Apartheid philosophy and its legacy was too strong for most of us. Based on seeing life through Master-Slave, Boss-Subordinate, Superior-Inferior, Rich-Poor, Educated-Illiterate, Advanced-Primitive, civilized-uncivilized relationships, this “baaskap” paradigm has engulfed us. Even when we know it is not desirable, we often find ourselves promoting it, advocating on its behalf through actions more than words.

It makes us feel acceptable and progressive to be seen as “the master.” We do everything and anything to feel accepted and to get approval from those who represent “the master” perspective. It has been engraved in us to look for this approval, otherwise we feel we do not have the capacity to stand by ourselves and achieve success on our own. The desire to be associated with, to be affiliated to, approved by, “the master” is hard to resist for most. It is this prevailing mentality in South Africa that undermined indigenous cultures, languages, restricted people’s movement and freedom to associate, to think, to explore, to design, to invent, to discover.

It is a “total control” approach of life. It attempts to control what people think and learn. Given the slightest opportunity, it dictates LIFE to each and every person who is supposed to be subordinated (and limited) to its wishes and desires.

In a cultural and socio-economic environment shaped by a social hierarchy long based on race, fertile ground exists for past tendencies to endure. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

Football under these conditions cannot be sustained, let alone developed.

Looking at football through a particular lens inevitably results in the game looking in a particular manner. Are we using proper African perspectives to look at the game as it is in Africa? Are our views coloured to give us a special feeling? Are we ready to bring something new to world football or are we content to follow established paths and continue to consume what is already in the market? We are entrepreneurs and have skills. We need to develop them and show our own ideas to the world. We need to create something new in our football for the world to sit up and take note.

Tag: Bafana Bafana

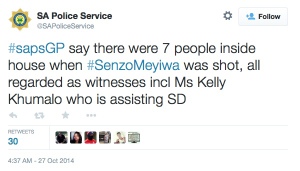

Just two days after former 800m world champion Mbulaeni Mulaudzi died in a car crash, South Africa mourns the death of another sport celebrity. 27-year-old Senzo Meyiwa, captain of Orlando Pirates and South Africa, was shot and killed on Sunday evening during a robber at his partner’s home in Vosloruus, East Rand.

According to initial reports, two armed men entered the home of actress and singer Kelly Khumalo and demanded cash, cell phones, and valuables from seven people. An altercation ensued and one of the assailants shot Meyiwa once in the chest. The player was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital.

According to initial reports, two armed men entered the home of actress and singer Kelly Khumalo and demanded cash, cell phones, and valuables from seven people. An altercation ensued and one of the assailants shot Meyiwa once in the chest. The player was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital.

Kick Off magazine reported on its website that “News of the shooting prompted widespread sympathy on social media and condemnation of South Africa’s rampant gun violence.”

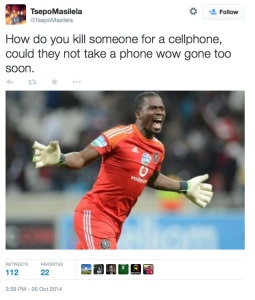

Tsepo Masilela, a Bafana Bafana teammate of Meyiwa’s, seemed to capture the shock of many when he tweeted: “How do you kill someone for a cellphone?”

Tsepo Masilela, a Bafana Bafana teammate of Meyiwa’s, seemed to capture the shock of many when he tweeted: “How do you kill someone for a cellphone?”

The South African Police Service (@SAPoliceService) offered a R150,000 reward for information leading to an arrest.

Chris Thurman, an academic and editor of Sport versus Art, summed up the horrible past days for sport in South Africa via Twitter: “RIP Mbulaeni Mulaudzi & Senzo Meyiwa. Men who offered South Africans two of the best features of our story, struck down by two of the worst.”

Quinton Fortune played seven seasons with Manchester United and 46 times for South Africa. On September 23, he wrote an excellent piece in The Guardian about a topic dear to me and to many readers of this blog: the impact of the 2010 World Cup on the growth and development of South African football.

Given the billions of rands spent on new and revamped stadiums and transport infrastructure, Fortune asks, was hosting the tournament a boon for the local game? “Judging by the poor attendances at top-flight games not involving the country’s two most popular clubs, Kaizer Chiefs and Orlando Pirates, who are also by far the most powerful in financial terms, and the poor performances of the national team Bafana Bafana, the answer unfortunately has to be a resounding ‘no’,” Fortune writes.

His concerns are numerous, important, and inter-related. The World Cup, Fortune asserts, did nothing to alter the Chiefs-Pirates duopoly, which continues to capture the lion’s share of the attention from fans, media, and sponsorship money. He points out that the quality of play in the Premier Soccer League is not terribly good, as evidenced by last year’s top scorer, Bernard Parker, boasting a meager 10 goals.

Fortune then notes how the swanky World Cup stadiums in Cape Town, Nelspruit, Polokwane, and Port Elizabeth are now massive financial drains on local municipalities struggling to deal with many pressing social needs in perhaps the most unequal country in the world.

The former Man United midfielder does not spare the PSL’s satellite broadcaster, SuperSport, which bankrolls the South African league while offering 24/7 matches and highlights of European football (such as EPL, La Liga, Serie A, Champions League). This contradiction is another reason why the PSL is “losing fans who prefer to watch the football from the comfort of their homes, receiving high definition pictures, while also having a choice of watching (better quality) football from other parts of the world,” says Fortune.

The way forward, Fortune concludes, requires harnessing South Africa’s world-class infrastructure and abundance of football talent to forge “a well-planned development programme which will develop that talent into realising its full potential.” How this should be done is the challenging part.

Guest Post by Liz Timbs (@tizlimbs)

Guest Post by Liz Timbs (@tizlimbs)

“We indeed have a crisis of monumental proportions. We don’t have a crisis of talent, we have a crisis of putting everything together,” thundered South African Sport and Recreation Minister Fikile Mbalula following South Africa’s 3-1 loss to Nigeria in Cape Town on Sunday, which eliminated the hosts from the 2014 African Nations Championship.

Mbalula publicly lambasted the national team, declaring that what he witnessed “was not a problem of coaching, it was a bunch of losers.” This “bunch of losers” and “unbearable useless individuals,” Mbalula continued, humiliated their country: “In Africa we have won nothing—we are the laughing stock. Even Madiba Magic would not have worked. This generation of players we must forget.”

Danny Jordaan, president of the South African Football Association and ex-CEO of the 2010 World Cup Local Organizing Committee, also criticized Bafana’s performance in the media, though in slightly less forceful terms than Mbalula. Jordaan saw the team’s elimination as an embarrassment, noting that SAFA had been “dismissive and even insulting to the quality of football on the continent.” He highlighted a deficiency in the “preparations, philosophy and technical staff.”

The reaction from Bafana Bafana head coach, Gordon Igesund, was decidedly tamer. “There are no excuses,” Igesund declared, “We lost to a better side . . . at the end of the day we have to look at ourselves and admit we were just not good enough even though we gave it our best shot.” Midfielder Siphiwe Tshabalala echoed Igesund’s understated honesty in his comments to the press. He apologized for the team’s debacle, adding that: “we are hurting and we know the nation is also hurting and we are not proud of not doing well but we just have to apply ourselves better in the future.”

Tshabalala and Igesund’s comments cut straight to the realities of why South Africa lost to Nigeria. Bafana certainly did not lose because goalkeeper Itumeleng Khune withdrew due to an ankle injury that threatened his participation in an upcoming Kaizer Chiefs league match against Mamelodi Sundowns. Let’s acknowledge the painful reality and move on: The South African national team is, at best, mediocre; we have to face this truth.

What makes digesting this bitter pill more difficult is that Nigeria did not even field her best team. The CHAN competition is limited to home-based players, which meant that Nigerians playing in European clubs were ineligible for selection unlike most Bafana regulars who ply their trade in the well-endowed domestic Premier Soccer League. Despite this apparent advantage, Bafana was no match for a team of young Nigerian players with limited experience in international competition. The visitors delivered three staggering blows and came close to a fourth before Bernard Parker scored a consolation penalty for the hosts.

Jordaan and Mbalula’s frustration with the national team is understandable. South African fans were frustrated watching the game. The problem is not that politicians and football officials were voicing their legitimate concerns, but rather the way in which they were framing these issues. These micro-level critiques, while useful in expressing frustration and releasing tension, are unproductive for getting to the root of South African football’s larger problems.

While not solely responsible, SAFA should be assisting in whatever way possible to develop talent at the grassroots level in order to eventually effect positive change at the highest level. Jordaan stated that SAFA is aware of the need for “big changes” at “grassroots level,” adding that “If we want to build a winning team for the future we have to have efficient structures in place right from school level.” Yet this vision is narrowly framed in terms of how this vaguely defined development would result in better showings by the senior national team.

Jordaan is right that grassroots development is desperately needed. But perhaps not in the ways he and others like Mbalula are suggesting. Mohlomi Maubane spoke to this important issue in a 2012 post on this blog. “SAFA’s understanding of the ‘bigger picture’ in domestic football is confined to four-year cycles for the men’s national team,” Mohlomi wrote. “But local football needs sound management, serious youth development for boys and girls, better coaches’ training, and infrastructural improvements at the grassroots.”

Using football as a tool for development not only helps to nurture athletic talent (as Jordaan noted) but also works to build healthy, productive members of society. As the remarkable work of Izichwe Football Club in Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal demonstrates, this kind of development takes time, work, and resources. While the results won’t be seen right away, South African football can move forward through community-based, player-centered, long-term, sustainable approaches to youth and coaching development.

Minister Mbalula was correct in one regard: “We indeed have a crisis of monumental proportions.” Hopefully, the latest Bafana loss will inspire South African sport administrators and partners to invest the necessary resources and knowledge to go beyond crisis management and move closer to fulfilling South Africa’s great football potential.

*Liz Timbs is a PhD student in African history at Michigan State University. Her research interests are in the history of health and healing in South Africa; masculinity studies; and comparative studies between South Africa and the United States. Follow her on Twitter: @tizlimbs.

Gordon Igesund named Bafana Bafana coach

It’s official: Gordon Igesund is the new Bafana Bafana coach. The well-travelled Durbanite was the outright favourite for the job, and his appointment is the climax of what has been a remarkable coaching career.

Igesund’s first coaching job was in 1985 as a player-coach for Witbank Aces. For the next 11 years, he mainly coached modest teams battling to avoid relegation, sometimes unsuccessfully. In 1992 he won the NSL Second Division title with D’Alberton Callies, but his rise to prominence began in 1996-97 when he guided Durban’s Manning Rangers to the inaugural PSL title. More league honors followed at Orlando Pirates (2001-02), Santos (2001-02), and Sundowns (2006-07), which made Igesund the only coach to annex the championship with four different PSL clubs.

His appointment as the national team coach on a two-year contract comes on the back of an impressive stint at the helm of Moroka Swallows. The fabled Soweto team sent Igesund an SOS eighteen months ago when they found themselves at the bottom of the table nearly halfway through the season. Igesund masterminded The Dube Birds’ great escape, and this season they had an astonishing year, finishing an agonising second to Orlando Pirates.

It is Igesund’s heroics at Moroka Swallows that SAFA expect him to emulate with beleaguered Bafana Bafana, currently ranked 68th in FIFA’s world rankings. South Africa’s qualification bid for the 2014 World Cup in Brazil is in serious jeopardy after draws against Ethiopia and Botswana. While South Africa’s hosting of the next edition of the African Nations Cup guarantees Bafana Bafana’s participation, there is well-founded anxiety in the country over the threat of an uninspiring showing in the tournament.

“The bigger picture is the 2013 AFCON and qualifying us for Brazil 2014,”declared SAFA President, Kirsten Nematandani, at Igesund’s unveiling. It’s the same brief former Bafana coach Pitso Mosimane was given two years ago. As SAFA made abundantly clear to Igesund, should the national team fail to reach the semi-finals of the African Nations Cup next year, then he will join Mosimane on the growing list of former Bafana coaches, which now stands at eighteen.

Igesund’s pedigree gives many South Africans hope that, despite recent results, he is indeed the manager who can lead Bafana to the continental crown and to the World Cup in Brazil. He is a wily old fox who has paid his dues in the trenches. He knows how to nurture self-belief and instil a desire to win into any team under his tutelage, regardless of available talent and financial resources. We wish him good luck in his new position.

There is a problem, however, that Igesund cannot solve even if he ends up meeting his new employers’ lofty objectives. That is, SAFA’s understanding of the “bigger picture” in domestic football is confined to four-year cycles for the men’s senior national team (or in this case a two-year cycle). But local football needs sound management, serious youth development for boys and girls, better coaches’ training, and infrastructural improvements at the grassroots. In other words, the goals SAFA has set for Igesund are no more than an attempt at a quick-fix solution.

SAFA would have done better to concede their administrative shortcomings, apologize for the dismal state of football in the country, and state that Igesund is the best bet for turning hapless Bafana Bafana into a winning team. Instead, SAFA hired the country’s most decorated coach and required him to take one of the least feared teams in Africa to the semi-finals of the continent’s premier tournament and then to the World Cup. While there is no question of Igesund’s success as a club coach, it would not be surprising if, after the 2013 African Nations Cup, he were to become the 19th Bafana coach in 20 years.

Spotlight on African Coaches

Editor’s Note: This post begins a multi-part series on African coaches.

Continuing with Pitso is Regressing

Guest Post by Mohlomi Maubane

SOWETO, SOUTH AFRICA — In a recent issue of Kick Off, South Africa’s leading soccer magazine, Editor Richard Maguire argued against firing Bafana Bafana coach Pitso Mosimane (in photo above). Pitso, of course, is singularly responsible for South Africa’s embarrassing failure to qualify for the 2012 African Nations Cup finals (aka The Comedy in Nelspruit). I have been collecting Kickoff since high school. As a magazine, it expects vision, competence and innovation from every member of the South African football fraternity; hence the editorial vouching for Pitso to stay on as Bafana Bafana coach was surprising.

The crux of Maguire’s argument is that Mosimane should remain in charge for the sake of continuity. I say there should not have even been a beginning. Mosimane’s coaching success has been overblown. At club level, he led well-endowed Supersport United to five cup finals, losing three, and at national team level he was an assistant coach during a mediocre run from 2006 to 2010, when Bafana sunk to 90th in the FIFA World Rankings.

The ridiculous manner in which South Africa failed to qualify for the 2012 African Nations Cup finals showed Mosimane to be as unprofessional as his employers. How can a national coach fail to read or grasp competition rules? This is a man who thinks of himself as a “modern” coach always in step with the latest developments in the world game. Perhaps common sense is not part of the curriculum of the courses Mosimane often brags of attending. And for all his supposed keeping abreast with the latest trends in the game, Mosimane’s idea of “global football” is confined to the English Premier League and La Liga.

SAFA appointed Pitso Mosimane as Bafana Bafana coach soon after the 2010 World Cup. At the time, there was talk of the dawn of a new era in South African football. In truth, there was the usual lack of specific detail on how to make this new epoch come about. Instead, SAFA officials spoke at length about Vision 2014, Bafana Bafana’s campaign to qualify for the World Cup in Brazil. The seven other national teams under SAFA’s auspices were left unmentioned. Now, a year after the Vision 2014 was unveiled, we are a joke in the football world.

More than anyone else, it was Mosimane’s job to ensure Bafana qualified for 2012. He was entrusted with the troops and should have known the rules of engagement. When he was introduced as the new Bafana coach after the World Cup, Mosimane was his typical pompous self, saying he did not expect favors from anyone, he knew his mandate, and that he wanted to be judged by the results. Here are the Nations Cup results: 2 wins, 3 draws, and 1 loss, 4 goals scored, 2 against. Having failed to qualify, his story has now changed. In his first press conference after the Comedy in Nelspruit, Mosimane had the audacity to say he did not fail because South Africa finished top of their group! That Bafana actually failed to qualify was in the past; it was time to move on, he said.

Indeed it is time to move on, and perhaps it is best to do so with a coach who reads and understands the rule book; one whose trophies and coaching acumen supersede his chest-thumping bravado. Pitso Mosimane has been in the national structures for more than five years and South African football would not be served well by a continuation of his underachievement.

If Mosimane were a football journalist and wanted to write for Kick Off, I suspect Maguire would send him away with the disdain he probably feels when the magazine has to document yet another SAFA cock-up.

Bafana Buffoonery

South African players embarrass themselves and the nation by dancing in celebration after a 0-0 home draw with Sierra Leone on October 9, 2011 in Nelspruit. Niger had qualified instead! (For details see yesterday’s post here.)