The Africanization of Italy may have started 2200 years ago as Hannibal of Carthage led his troops and elephants across the Alps on the way to Rome, but Mario Balotelli’s two-goal performance in Italy’s defeat of Germany in the Euro 2012 semifinal may be mainstreaming it.

The Africanization of Italy may have started 2200 years ago as Hannibal of Carthage led his troops and elephants across the Alps on the way to Rome, but Mario Balotelli’s two-goal performance in Italy’s defeat of Germany in the Euro 2012 semifinal may be mainstreaming it.

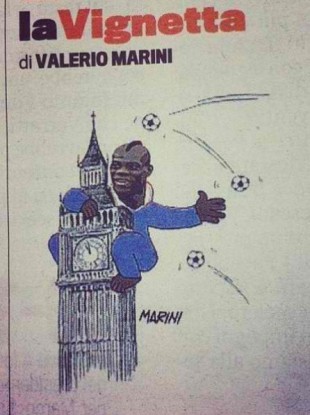

Italians across the political spectrum are gushing in their praise of the 21-year-old striker. “Pride of Italy!” screamed the web site of La Gazzetta dello Sport, which earlier in the week had printed an insulting cartoon of Balotelli as King Kong by Valerio Marini (see below). (Despite an outpouring of criticism from readers and on social media, the paper could only muster this sad excuse for an apology: “if certain readers found the cartoon offensive, we apologize.”)

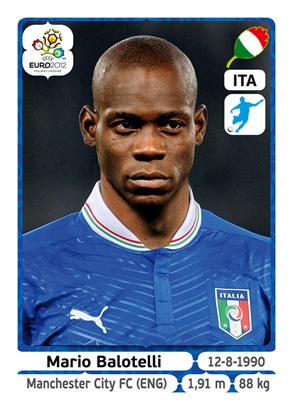

Earlier in the tournament Balotelli had won accolades for his acrobatic overhead strike against Ireland and for his impeccable penalty which opened the shootout against England (scored against Man City teammate Joe Hart). Now, on the eve of the final against Spain in Kiev, ordinary Italians and the media are comparing Balotelli to Gigi Riva, Totò Schillaci, and Gianluca Vialli — illustrious Azzurri of the past who transcended the football pitch to become popular icons of national culture. A big and very noticeable difference between Super-Mario and his predecessors, of course, is that Balotelli is black — the Palermo-born son of the Barwuahs from Ghana who was adopted by the Balotellis of Brescia. He is the first Afritalian football superstar.

Super-Mario’s central role in potentially ushering in a new phase in the Africanization of Italy is reflected in Italian media stories highlighting how Mario is like you and me: he loves football, family, pizza, and hanging out with his friends. In a country where mothers are sacred and where the Virgin Mary is venerated almost as much as her more famous son, Mario’s loving embrace of Mamma Silvia in the stands at the Warsaw stadium shot an arrow into the heart of every Italian. “Boastful and ‘mammone’, Balotelli represents the prototype of the Italian,” wrote Il Giornale, a conservative paper owned by Silvio Berlusconi’s brother, Paolo.

And Balotelli is not an isolated case; he’s not even the only Afritalian in the Euro squad. Sitting on the reserves’ bench is 24-year-old Angelo Obinze Ogbonna (at left), a central defender who plays his club football for Torino. Born in Cassino, near Rome, of Nigerian parents, Ogbonna was recruited into the Torino youth academy at age 14 and played his first serie A match at 19. Like Balotelli, Ogbonna speaks Italian without a trace of accent. The experiences of Super-Mario and Ogbonna open up an opportunity to consider the history of Afritalian footballers.

And Balotelli is not an isolated case; he’s not even the only Afritalian in the Euro squad. Sitting on the reserves’ bench is 24-year-old Angelo Obinze Ogbonna (at left), a central defender who plays his club football for Torino. Born in Cassino, near Rome, of Nigerian parents, Ogbonna was recruited into the Torino youth academy at age 14 and played his first serie A match at 19. Like Balotelli, Ogbonna speaks Italian without a trace of accent. The experiences of Super-Mario and Ogbonna open up an opportunity to consider the history of Afritalian footballers.

Let’s start with Claudio Gentile. He was born in Tripoli, the son of a Sicilian father and a Tripoli-born mother possibly of Italian background, and grew up playing street football in Libya before moving to Como in 1961 with his family. Nicknamed “il libico,” Gentile had his best years at right back for Juventus and Italy in the 1970s and early 1980s, forming with Dino Zoff, Antonio Cabrini, and Gaetano Scirea one of the stingiest defensive lines of all time. Gentile’s ferociously effective man-to-man marking of Maradona and Zico in the 1982 World Cup, which Italy won, has become the stuff of legend.

We had to wait nearly two decades for the next Afritalians to make an appearance in the national team. In 2001, Fabio Liverani, the Rome-born son of a Somali mother and Italian father, made his international debut in a friendly against South Africa. Despite a solid career as a midfielder with Lazio, Fiorentina, and Palermo, Liverani only played twice more for the Azzurri. Around the same time, Matteo Ferrari, the Algeria-born son of an Italian father and a Guinean mother, played eleven times in the heart of Italy’s defense. Prior to Balotelli’s success, Ferrari had held the record for most international appearances for an Afritalian. (He now plays for the Montreal Impact in MLS.)

There are other players of African blood in Italian football. Among them, Stephan El Shaarawi, Stefano Chuka Okaka, and Fabiano Santacroce (of Afro-Brazilian/Italian parentage) have been capped at junior level. There is also a female Afritalian: left back Sara Gama (at right), who also earned the distinction of becoming the first Afritalian woman to captain the U-19 national team, and leading them to the 2008 European title.

There are other players of African blood in Italian football. Among them, Stephan El Shaarawi, Stefano Chuka Okaka, and Fabiano Santacroce (of Afro-Brazilian/Italian parentage) have been capped at junior level. There is also a female Afritalian: left back Sara Gama (at right), who also earned the distinction of becoming the first Afritalian woman to captain the U-19 national team, and leading them to the 2008 European title.

Mauro Valeri, a sociologist and author of La Razza in campo: Per una storia della Rivoluzione Nera nel calcio (EDUP, 2005) wonders if the increasing presence of black players at junior and senior level is “perhaps a sign of a transformation underway, of the affirmation of a Black Revolution [in football] that for more than a decade has been unfolding in Italy.” While structural changes would be necessary for such a shift to be lasting and meaningful, social perceptions of Afritalians may be changing thanks to Balotelli’s sudden popularity. In a grim age of austerity and structural adjustment, Italians seem eager for another taste of Super-Mario-triggered football euphoria.

Tag: Euro 2012

Super-Mario Balotelli wrote a new page in Germany’s History of Failure against Italy in Warsaw today. He scored two goals, the first a header off a delightful Cassano cross; the second a thunderous strike from outside the box, which he celebrated in inimitable style (photo above). He is Italy’s pride and joy.

Manager Cesare Prandelli did his part as well, completely outcoaching his German counterpart Jogi Loew. Italy now moves on the final against Spain on Sunday in Kiev.

Full Italy-Germany highlights courtesy of UEFA.com here.

Germany’s History of Failure Against Italy

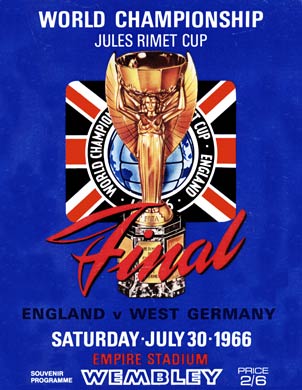

Germany is favored to win Thursday’s Euro 2012 semifinal against Italy. While Die Manschschaft has played the best and most consistent football in the tournament, the Azzurri have won just one game in regulation and reached the semifinal only after surviving a penalty shootout against England. History provides a counterpoint to soccernomics-style prognostications, however, because the Germans — or West Germans — have never defeated Italy in Euros or World Cup tournaments.

It started with a forgettable goalless draw at the 1962 World Cup in Santiago del Chile, but ignited in a globally televised World Cup semifinal played at the Azteca Stadium in Mexico City on June 17, 1970, which Italy won 4-3 in extra time. Outside the Azteca a plaque commemorates it as “The Match of the Century.” The video above combines footage of the original broadcast with Fabio Caressa’s 21st-century play-by-play commentary. Rumor has it that this clip is streaming on a loop in the Azzurri’s team hotel . . .

Come back tomorrow for part 2 of Germany’s history of football failure against Italy.

Author, scholar, and journalist David Goldblatt is probably best known for his sacred text of football studies: The Ball is Round: A Global History of Soccer. On Thursday, March 15 (The Ides of March!), Goldblatt shared work from his new project — a sort of mini-Ball is Round book on the cultural politics of football in Britain after 1989.

Author, scholar, and journalist David Goldblatt is probably best known for his sacred text of football studies: The Ball is Round: A Global History of Soccer. On Thursday, March 15 (The Ides of March!), Goldblatt shared work from his new project — a sort of mini-Ball is Round book on the cultural politics of football in Britain after 1989.

In an engaging public talk at the Department of History at Michigan State University, Goldblatt used the upcoming European Championships in Poland/Ukraine and the London Olympics, to explore the changing relationship between football, Britishness, and Englishness in the age of devolution.

The spontaneous popular theater of the Euros, he argues, carves out an arena for England’s traveling fans to declare their “Englishness.” Fans’ rejection of the Union Jack in favor of the flag of St. George and their performance of particular national songs are cases in point. In the case of the 2012 Olympics, Goldblatt notes that there will be no “England” in the tournament because the International Olympic Committee, unlike FIFA, deals only with sovereign states. (Britain has four members in FIFA: England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.) The formation of the British Olympic football team thus becomes very contentious in a postdevolution context, with only England firmly supporting it. A striking contemporary example of football’s singular significance for popular national identity.

Listen to Goldblatt’s talk here.