“Beyond the Pitch” is a riveting BBC World Service radio documentary that explores the close links between the “beautiful game” of football and the “dirty game” of politics in multiple African countries.

Produced by Farayi Mungazi and Penny Dale, the 50-minute feature aired on the eve of the 2017 Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) in Gabon, which marks the 60th anniversary of the continent’s most prestigious sporting event.

The documentary opens with Nigeria’s boycott of AFCON 1996 in South Africa. The last-minute withdrawal of the Super Eagles came in retaliation for President Nelson Mandela’s scathing criticism of Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha’s regime, which in November 1995 had executed author Ken Saro Wiwa and eight more Ogoni environmental activists in a sham trial.

The next segment is captivating and among the most historically significant. It tells the story of how football helped Algeria’s struggle for independence from France through mesmerizing interviews with Mohamed and Khadidja Maouche. He was a young professional footballer in France in the late 1950s, but the newlyweds were also members of the National Liberation Front (FLN), the main Algerian liberation movement. The couple reveals how they secretly worked together to facilitate an exodus of Algerian-born footballers from their French clubs to play for the FLN “national” team. “No-one knew I was married to Maouche,” Khadidja says. “They would just be told a FLN activist wanted to speak to them. I would talk to them individually to say: ‘It’s an order, that’s it,’ and they all agreed.” In 1960 Mohamed Maouche eventually joined the FLN team, which played matches in front of large crowds in North Africa, the Middle East, East Asia, and Eastern Europe. “We were the first ambassadors of the revolution and the Algerian people,” he recalls with profound emotion half a century later.

Burundi’s current President Pierre Nkurunziza, a qualified football coach and owner of Hallelujah FC, is mentioned as a bridge to a terrific interview with Dr. Hikabwa Chipande, an historian and Michigan State University alumnus (PhD, 2015). Now a lecturer in African history at the University of Zambia, Chipande brings the BBC reporter through the archives in Lusaka where he conducted doctoral research on the history of Zambian football. As they look at sources documenting former president Kenneth Kaunda’s passion for and involvement in the game, Chipande points to a 1974 photograph of Kaunda serving food to the national team—quite an endearing, populist image. Mungazi then travels to Luanshya, on the Copperbelt, to talk football and politics with Dickson Makwaza, one of the players served by Kaunda in 1974, and with 91-year-old Tom Mtine, a legendary football administrator.

In the second half of the documentary we leap ahead to AFCON 2010 in Angola. The Togo national team bus was targeted by armed separatists from the enclave of Cabinda at the border with the Republic of Congo: “probably the most dramatic moment ‘off the pitch’ in the history of the Africa Cup of Nations,” Mungazi says. The armed attack killed two men and wounded several others: “one of the worst experiences I’ve had in my life,” said Togolese striker and English Premier League veteran, Emmanuel Adebayor.

The last time Uganda qualified for AFCON was in 1978 when the infamous Idi Amin was still in power. A local academic and former national team players explain how Amin, a keen boxer himself, bankrolled sports during his dictatorship (1971-79) to boost nationalism and also as a weapon of mass distraction. But we also hear of the traumatic experiences of John Ntensibe and Mama Baker. The former was imprisoned and forced to load bodies onto trucks after scoring the winning goal for Express FC against the army team, Simba, while Baker, a devoted Express supporter, was arrested twice for little more than being Uganda’s biggest soccer fan.

Fast forward again to the 21st century: we hear about George Weah, Africa’s only World Player of the Year (1995), who launched a career in politics in Liberia after retiring from the game. Weah lost a presidential election in 2004 (to future Nobel Peace laureate Ellen Sirleaf Johnson), but recently won a Senate seat and may run again for his country’s highest office.

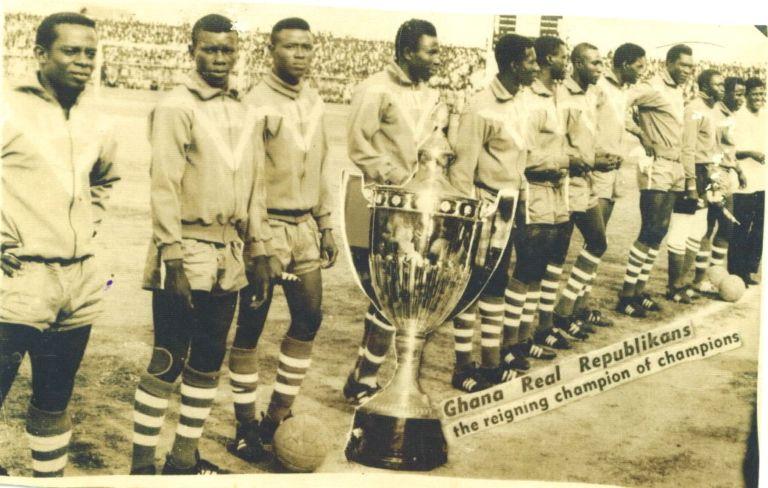

The final chapter in the story of the links between politics and football focuses on Ghana. There, top clubs Accra Hearts of Oak and Kumasi Asante Kotoko have long been entangled in party politics and presidential contests. Veteran Ghanaian reporter Kwabena Yeboah also describes the emergence of Real Republikans, a super club of the 1960s closely connected to President Kwame Nkrumah. Subsequent regimes in Ghana, it is noted, used the men’s national team, the Black Stars, to strengthen their popularity and “perpetuate their reign.”

As a scholar who has been writing about African football history, culture, and politics for a long time, I found Farayi Mungazi and Penny Dale’s “Beyond the Pitch” documentary to be finely researched and evocatively presented through African voices. The producers did well to carefully bring out the game’s contradictory capacity to be a force for empowerment and disempowerment. What a great way to get ready for the upcoming 2017 AFCON in Gabon. And what a wonderful resource for teaching and research.

Click here to listen and download the podcast version of the documentary.

Tag: Hikabwa Chipande

Zambia won the African Nations Cup in 2012. It is a recognized regional football powerhouse. As in most African countries, Zambians are fiercely passionate and knowledgeable about the game.

Yet to this day no academic history of soccer in Zambia exists. Hikabwa Decius Chipande, a native of Zambia currently completing his PhD in history at Michigan State University, is determined to eliminate this inexcusable oversight.

On March 26, the Football Scholars Forum, a fútbol think tank based in the MSU History Department, hosted an online discussion of Chipande’s paper titled “Mining for Goals: Football and Social Change on the Zambian Copperbelt, 1940s to 1960s.” This paper is part of Chipande’s larger doctoral dissertation in African history, which I am supervising at MSU.

The paper was precirculated on the FSF website and then, following the group’s tradition, the author was invited to make brief introductory remarks about the project before ably taking questions from the audience for 90 minutes.

Participants from three continents engaged in a discussion about the changing structure of clubs on the Zambian Copperbelt; sport in Africanist scholarship; the place of Zambia in wider south-central and southern African histories; local fan culture; and the importance of print media and oral interviews to represent multiple local voices and perspectives on the past.

The audio recording of the full session can be downloaded here.

Zambian Fútbology

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

LUSAKA—On June 4, 2014, I was invited by Dr. Walima Kalusa, the University of Zambia’s History Department head, to present a fútbological paper based on my current doctoral research on the political and social history of football in Zambia (1940s-1993). The seminar on “Football and Social Change on the Northern Rhodesian Copperbelt, 1940s to 1960s” was well attended by UNZA History staff, graduate students, and other interested scholars.

I explored how urbanized African miners appropriated football from their European supervisors and, after World War II, created a new black popular culture. When colonial authorities and mining companies introduced post-War social welfare programs to appease miners and urban residents, local Africans used these structures to demand greater access to resources for organized football and other amenities in their communities. In the late 1940s and into the 1950s, Africans popularized the game on the Copperbelt and used it to build vibrant social networks and communities to replace what they left in their rural villages.

As early as 1937, the British had established the Central Native Committee, which seized control of African sport due to fears that the colonized might use football as a tool for political agitation. Despite these moves, ordinary African athletes, officials, and fans developed alternative ways of organizing and enjoying their football. For example, supporters clubs formed. These hard-core fans unexpectedly made club officials and mine managers more accountable to the people. The emerging vernacular fan culture, which no scholar has ever researched before, shows how Zambians were sometimes able to use sport to rework the application of harsh colonial policies.

Another aspect of the history of Zambian football that has eluded researchers has to do with international matches played in colonial times. As I have discovered, Copperbelt teams played in the Belgian Congo, Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), and South Africa. My work illustrates how these sporting adventures, among other things, turned into incubators for Pan-Africanism because the camaraderie experienced by Zambians in these contests sharpened their sense of solidarity with fellow Africans in neighboring colonies.

Guest Post by Hikabwa Chipande (@HikabwaChipande)

LUSAKA—Zambia is mourning football radio commentator Dennis Liwewe, who died on April 22, 2014, at the age of 78.

LUSAKA—Zambia is mourning football radio commentator Dennis Liwewe, who died on April 22, 2014, at the age of 78.

Liwewe caught the soccer fever on the Copperbelt in the late 1950s and 1960s, an era that led to the emergence of great players such as Samuel “Zoom” Ndlovu, John “Ginger” Pensulo and Kenny Banda. He became the first black football commentator in the early 1960s before Zambia’s independence. Liwewe’s passionate radio broadcasts made him a household name among ordinary Zambians. At a time when there was no television, Liwewe’s enthusiastic and absorbing descriptions of matches helped popularize the game across the country.

By the mid 1970s, he was known as a prominent football announcer in neighboring countries such as Tanzania, Malawi, Zimbabwe and Botswana. When Zambia reached the final of the 1974 African Cup of Nations finals in Cairo (which Chipolopolo lost to Zaire [now DR Congo]), the Egyptian weekly magazine Al-Musawar labeled Dennis Liwewe the greatest football commentator south of the Sahara. He drew favorable comparisons with the famous Egyptian radio and television broadcaster Mohamed Latif. (Latif had played for Egypt’s national team in the 1930s, then became a referee in the 1940s, before going on to earn the nickname “Sheikh of Commentators” in the 1950s.)

From the 1960s to the early 1990s, football on the radio was synonymous with Dennis Liwewe. His emotionally loaded calls made listeners of all ages in towns and villages around the country visualize what was happening in a stadium far away. He could estimate and explain all free-kick angles, distances to the goal, and the speed of the ball in a vivid and unmistakable voice. He had that distinctive ability to carry listeners with him, bringing enjoyment to their lives and even making them proud to be modern Zambians. It was not uncommon to hear both young and old people reciting and imitating his soccer commentaries, a kind of oral literature. No wonder Zambians felt that broadcasters who did not announce like Liwewe were just not good enough.

Even after the introduction of the Mwembeshi satellites and television broadcasts in 1974, Liwewe’s radio work remained popular. It was common for soccer fans to watch live matches on television with the volume turned down to listen to Liwewe on the radio. Many fans also went to Independence Stadium in Lusaka carrying two-band radios so they would not miss Liwewe’s entertaining narration. My good friend Mtoniswa Banda reminded me that another reason why fans carried radios to the stadium was because Liwewe often exaggerated or made up his play-by-play commentary. Even when the action was dull and distant, he could narrate it as if it were only a few inches from the goalposts! Other Zambian supporters also note that Liwewe became too commercial in his old age, to the point that he demanded to be paid in cash for an interview about the history of the game.

Aside from his radio work, Liwewe was employed by the Mining Mirror as a sports reporter for the Nchanga Consolidated Mines in Chingola. Subsequently, he rose to the position of Director of Public Relations of the Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines (ZCCM) before retiring in 1985.

Dennis Liwewe’s name in Zambia evokes memories of young people in urban townships and rural villages assembling makeshift radios, repairing (or buying) new ones, putting their old batteries out in the sun hoping to get enough power to listen to their favorite football announcer. History will show that here in south-central Africa his voice, passion, and imagination were not only admired, but loved, like the beautiful game itself.

The latest Cowries and Rice podcast features Michigan State University History PhD candidate Hikabwa Decius Chipande discussing China’s stadium diplomacy in Zambia. Intriguingly, the enterprising hosts of the podcast, Winslow Robertson and Dr. Nkemjika Kalu, contacted Chipande in Lusaka after reading his “China’s Stadium Diplomacy: A Zambian Perspective” post on this blog.

In the interview (listen above), Chipande expands on his original contribution to explore several key aspects of the national and international politics of stadium construction in contemporary Zambia. Chipande shares his expert view on Zambian responses to the new arenas, inspired by Elliot Ross’s recent essay on the topic for Roads & Kingdoms, and contextualizes them within larger Chinese investments in mining and other sectors of the economy in south-central Africa.

Chipande is a recipient of the FIFA Havelange Research Scholarship for his doctoral dissertation on the social and political history of football in Zambia, 1950-1993. Reach out to him on Twitter at @HikabwaChipande.

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

“If you want to see the heart of China’s soft-power push into Africa,” writes Elliot Ross in a recent piece for Sports Illustrated’s “Roads & Kingdoms” series, “you’ll find it in the continent’s new soccer stadia.”

I am one of the many Zambians saddened that most of our national team matches are now staged at the Chinese-built Levy Mwanawasa Stadium in Ndola, an industrial town on the Copperbelt 200 miles north of the capital, Lusaka. This is not only because I live in Lusaka, where the team used to play its home games, but also because the move greatly diminishes, if not erases, the deeper significance of historic football venues.

It was in Lusaka’s then-newly constructed Independence Stadium on October 23, 1964, that the Union Jack was lowered and the new Zambian flag raised at midnight in a sumptuous ceremony attended by the Princess Royal and Kenneth Kaunda’s new cabinet. The following day, the stadium hosted the final of the Ufulu (independence) tournament. Ghana’s Black Stars, reigning African champions, beat Zambia 3-2 in front of about 18.000 spectators. From then on, almost all important international matches (as well as domestic cup finals) were played at Independence Stadium, a local example of how stadiums in postcolonial Africa, “quickly became almost sacred ground for the creation and performance of national identities” (Alegi, African Soccerscapes, p. 55).

Occasionally, Dag Hammarskjöld Stadium in Ndola hosted big matches. Constructed by the Ndola Playing Fields Association during the colonial era, this ground was rechristened in honor of the Swedish Secretary-General of the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjöld, who died in 1961 in a plane crash near Ndola. After the British colony of Northern Rhodesia became independent Zambia, the stadium was donated to the Ndola City Council. As the largest stadium in the Copperbelt, the traditional hub of football in the country, it hosted virtually every important match in the region.

In January 1986, the Zambian government bought into the idea of hosting the 1988 African Nations Cup finals. Mary Fulano, then a member of the Central Committee in charge of sport, informed the public that the government had started renovating both Independence and Dag Hammarskjöld stadiums. But in December 1986, after Dag Hammarskjöld stadium had been demolished for its planned reconstruction, Youth and Sport minister Frederick Hapunda announced that government had withdrawn its bid to host the 1988 tournament.

Copperbelt residents complained that they needed their beloved stadium, but the government kept on issuing empty promises. Surprisingly, two decades later, when an opportunity arose to build a new stadium in Ndola courtesy of China, the Zambian government opted for a completely new Levy Mwanawasa Stadium in a different area, thereby burying the rich history of Dag Hammarskjöld Stadium.

In 2012, I attended the inauguration of the Levy Mwanawasa Stadium: a 2014 World Cup qualifier between Zambia and Ghana (see my blog post about it here). The atmosphere at the venue was similar to the one described by Elliot Ross at the Estádio Nacional do Zimpeto in Maputo. Unlike the game in Maputo, however, there was no pushing and shoving at Levy Mwanawasa, thanks to plenty of available space and sound event management. But the stadium was so vast that the crowd could not sing and chant cohesively, or create the electrifying atmosphere so many of us treasure at football grounds.

The ignominuous end for Independence Stadium in Lusaka came after FIFA inspectors in 2007 declared it unsafe for international matches. As a temporary solution, the Football Association of Zambia moved internationals to Nkonkola Stadium in a small mining town on the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo. Bolstered by another Chinese loan, the Zambian government then erected a new National Heroes Stadium directly across from Independence Stadium and the graves of national team members who perished in the Gabon air crash of 1993.

The demolition of Independence Stadium prompted many people to wonder why the government chose not to renovate the hallowed ground and build the Chinese-funded stadium somewhere else in Lusaka. While younger Zambians tend to like the new sporting arenas, many older fans lament the disappearance of stadiums they associate with the stories of their personal lives, their memory, their past.

Regardless of age and status, Zambians are very much aware of “Chinese soft diplomacy.” People know that Chinese stadiums have less to do with friendship or mutual cooperation and more with gaining access to Africa’s material resources. Yet there is very little that can be done about it because the government does not consult with citizens on economic deals with China. There is criticism about Chinese firms bringing very cheap laborers to work in construction sites. But there seems to be a general feeling among the population that it is acceptable for the Chinese to build stadiums and other infrastructure in exchange for copper because the alternative is allowing Zambia’s political leaders to pocket the profits from this wealth.

—

*Hikabwa Chipande is a PhD candidate in History at Michigan State University. He is a recipient of the FIFA Havelange Research Scholarship for his doctoral dissertation on the social and political history of football in Zambia, 1950-1993. Follow him on Twitter at @HikabwaChipande

Football and Independence in Zambia

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

LUSAKA—On a rainy Friday evening at the Pamodzi Hotel, Zambia Open University Professor Ackson Kanduza, president of the Southern African Historical Society, convened a forum based on my paper “Football and Independence in Zambia: A Political and Social History 1950s-1964.”

Part of my doctoral research on colonial and postcolonial Zambian football, the paper draws on archival, newspaper, and oral sources to argue that the changing culture of the African game influenced the anti-colonial nationalist struggle by fighting racial segregation and promoting African leaders to highly visible and prestigious administrative positions before independence.

In the early 1960s, colonial racism in then-Northern Rhodesia was still intense. Segregation kept Africans out of European-owned shops and forced black customers to shop through a window instead; Africans were not allowed to enter whites-only train carriages and buses; and jobs paying higher wages were reserved for whites.

But in 1961-62, black and liberal white businessmen founded the nonracial (racially mixed) National Football League. A black man, Tom Mtine, was named chairman of an otherwise white-dominated league executive. Two years prior to independence, the NFL permitted black players to be on the same teams as whites, and Africans were also allowed to represent the territory in international competitions. The emergence of black administrators like Tom Mtine and the game’s function as a “neutral” cultural form among people speaking 73 languages helped to assert black power as well as a sense of Zambian-ness that cannot be ignored in the history of Zambia.

An audience of both academics and members of the general public posed interesting questions and offered constructive comments. Most participants agreed with me that these sporting events signified an important step towards political freedom. Some noted that as Zambians celebrated their country’s 40th independence anniversary, my historical evidence about black leaders in football and the hosting of an international football tournament in 1964 to celebrate the nation’s birth would be highly appreciated by millions of Zambians. The discussion also grappled with the seemingly contradictory evidence that the British believed the game to be part of the “white man’s burden” while local people used it to fight colonial oppression.

“I did not know that our football has such a rich history,” said Pride Mwaanga; “I was wondering about the connection between football and independence, but now it makes sense!” Other participants asked why this rich history of Zambian football has not yet been explored. Echoing the conclusions of Marissa Moorman’s recent history of music and nationhood in the musseques (shantytowns) of colonial Luanda, Angola, audience members highlighted how, unlike anti-colonial political leaders, Zambian football administrators and players’ contributions to building the Zambian nation are not recognized in typical historical accounts.

Participants also stressed the need to publish biographies of past footballing greats such as “Ucar” Godfrey Chitalu, Dickson Makwaza, John “Ginger” Pensulo and many, many others. Professor Moses Musonda, Zambia Open University Deputy Vice Chancellor, pointed out that we need more scholars to research and write the history of football in Zambia, otherwise we are going to lose this valuable past.

Other interesting contributions came from Mrs. Kanduza and, again, from Prof. Musonda, who both gave testimonies of how they experienced leisure activities in welfare centers during the colonial era. These social centers played a critical role in the development of football. Prof. Musonda stated that Europeans enforced separate social institutions such as welfare halls to make sure that young Africans did not have the opportunity to challenge young Europeans in sport. Ironically, the same welfare centers and sporting facilities helped African men and women build their self-esteem and were later turned into avenues for political agitation.

Prof. Kanduza concluded the event by pointing out that a goal of the Zambia Open University is to organize forums that give opportunities to listen to unheard local voices. He highlighted how the research and discussion of “Football and Independence in Zambia” captures voices and conveys the historical experiences of African people through the prism of sport. The evening ended with a promise to organize more of these lively and insightful sessions in the near future.

—

*Hikabwa Chipande is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at Michigan State University. He is currently in Lusaka researching the social, cultural and political history of football in colonial and postcolonial Zambia. Follow him on Twitter at @hikabwachipande