The Football Scholars Forum, the online think tank based at Michigan State University, recently explored fascinating aspects of the long and complex relationship between fútbol and politics in the history of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

The Football Scholars Forum, the online think tank based at Michigan State University, recently explored fascinating aspects of the long and complex relationship between fútbol and politics in the history of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

In its second session of the 2015-16 season, FSF co-founder Alex Galarza, PhD candidate in History at Michigan State, shared a chapter from his dissertation: “Dreaming of Sports City: Consumption, Urban Transformation, and Soccer Clubs in Buenos Aires.” Galarza’s doctoral research has been funded by prestigious national and international grants, including the coveted Fulbright and FIFA Havelange scholarships.

The potential impact of Galarza’s dissertation work beyond the ivory tower of academia can be gleaned from his involvement in an ongoing documentary film project. Working with four young Argentine journalists, Galarza aims to use the format of filmmaking to reveal the “hidden” history of Boca Juniors’ Ciudad Deportiva—a (failed) urban renaissance construction project that sheds new light on the role of professional soccer clubs in city planning and everyday life. (Watch the trailer here.)

The Forum encouraged Galarza to explain how this history of Buenos Aires compares with the experiences of other Latin American cities, and broader processes of modernization and state formation. The author and participants also discussed constructions of race, whiteness, and gender through fútbol, the politics of club governance, and the ideological projects behind stadium construction.

Listen to or download the audio recording here.

Tag: History

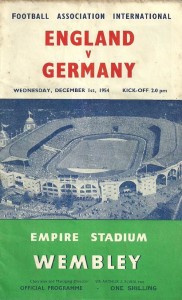

The Football Scholars Forum opened its 2015-16 season on Wednesday, October 14, with a discussion of Christoph Wagner’s DeMontfort University PhD thesis entitled “Crossing The Line: The English Press and Anglo-German Football, 1954-1996.”

The Football Scholars Forum opened its 2015-16 season on Wednesday, October 14, with a discussion of Christoph Wagner’s DeMontfort University PhD thesis entitled “Crossing The Line: The English Press and Anglo-German Football, 1954-1996.”

Based on extensive archival research, “Crossing the Line” analyzes representations of Germany and Germans in English newspapers’ football coverage of key international matches between the two western European nations. Within a shifting post-war historical context, the study notes a persistent undercurrent of hostility in Anglo-German cultural relations, football included.

However, two distinct phases were described. In the first, extending from the 1950s to the rise of Thatcher, dailies generally adopted a restrained tone and their coverage was notable for the “relative absence of anti-German sentiment.” A major transformation occurred in the second phase, from the 1980s to the mid-1990s, as English press coverage turned more negative, chauvinistic, and increasingly xenophobic.

The FSF discussion with the author touched on many different aspects of Wagner’s study, from the militarization of language in the football press and the forging of national stereotypes to narratives of English decline, methodology and sources.

A recording of the session is available here.

For more information about the Football Scholars Forum visit the online think tank’s website.

Zambia won the African Nations Cup in 2012. It is a recognized regional football powerhouse. As in most African countries, Zambians are fiercely passionate and knowledgeable about the game.

Yet to this day no academic history of soccer in Zambia exists. Hikabwa Decius Chipande, a native of Zambia currently completing his PhD in history at Michigan State University, is determined to eliminate this inexcusable oversight.

On March 26, the Football Scholars Forum, a fútbol think tank based in the MSU History Department, hosted an online discussion of Chipande’s paper titled “Mining for Goals: Football and Social Change on the Zambian Copperbelt, 1940s to 1960s.” This paper is part of Chipande’s larger doctoral dissertation in African history, which I am supervising at MSU.

The paper was precirculated on the FSF website and then, following the group’s tradition, the author was invited to make brief introductory remarks about the project before ably taking questions from the audience for 90 minutes.

Participants from three continents engaged in a discussion about the changing structure of clubs on the Zambian Copperbelt; sport in Africanist scholarship; the place of Zambia in wider south-central and southern African histories; local fan culture; and the importance of print media and oral interviews to represent multiple local voices and perspectives on the past.

The audio recording of the full session can be downloaded here.

This is my video blog contribution to the Football Scholars Forum roundtable taking place on Saturday, April 12, 2014, at the global fútbological conclave known as the Soccer as the Beautiful Game conference at Hofstra University in New York.

These pre-conference blog posts are intended to launch the discussion about points of overlap and tension in the soccer writing of journalists and academics. Roundtable participants will share their insights on sources and methodologies, topics, audience, market logic vs. academic logic, and the role of digital tools in writing and dissemination.

The rest of the roundtable team is composed of Simon Kuper (Financial Times), Brenda Elsey (historian, Hofstra U.) Alex Galarza (Michigan State U.), John Foot (U. Bristol), and Grant Wahl (Sports Illustrated). To read their posts visit: http://footballscholars.org

Sunday’s clásico was made for Ray Hudson’s commentary: like a “hair dryer in a hot tub” to use his magisterial description of Iniesta’s opening goal. I was happy with the outcome since I’ve had a soft spot for Barça for a long, long time. It dates back to my older brother in 1977 (or thereabouts) taking me to see Sandro Ciotti’s Il Profeta del Gol—a film about Cruyff with jaw-dropping goals from his azulgrana days. In honor of the Dutch genius, I even wore number 14 in high school and college back when I daydreamed about walking out of the tunnel at Camp Nou to take on Real Madrid.

Given all that, it’s the perfect time to review Sid Lowe’s Fear and Loathing in La Liga: Barcelona vs Real Madrid for today’s Football Scholars Forum.

Lowe, as readers of this blog probably know, is a noted fútbol journalist who writes about Spanish football for The Guardian and other major media outlets. He is also a rare sports reporter with a PhD (in History from the University of Sheffield in 2008 with a thesis on “The Juventud de Acción Popular in Spain, 1932-1937”). For a long time the biggest game in the world was not called el clásico but the derbi (p. 18). This book is a gold mine of such futbological facts and statistics. But the most revealing part of the journey, at least for me, came from its analysis and contextualization of the rivalry’s social and political dynamics.

The author’s academic training and sensibility is brought to bear on Fear and Loathing in La Liga in a number of ways. First, the chronological structure of the book. Second, the rich and diverse sources include government documents, minutes of club meetings, newspaper archives, newsreels, and many oral interviews with elderly protagonists, famous players, and club directors. (Regrettably, the commercial publisher decided to present the book without citations, probably for fear of alienating general readers.) Third, the book situates the fútbol rivalry within the larger context of a changing Spain. Fourth, it eagerly and ably goes beyond simple binaries that simplify the rivalry to just Spain vs. Catalonia, or in Lowe’s words: “Madrid fascists; Barça civil war losers. Madrid civil war victors and repressors; Barça left, Madrid right; Barça good, Madrid bad” (p. 12).

Lowe deploys the historian’s literary device of the potted biography to both complicate the facile dichotomy and to humanize his story. Two brilliant early chapters, for instance, focus on Barça and Madrid presidents during the civil war: Josep Sunyol (“The Martyr President”) and Rafael Sánchez Guerra (“The Forgotten President”). Having examined the historical evidence, Lowe debunks part of the political mythology of Barcelona. He reminds us that Madrid was where the civil war was fought, not Barcelona and argues persuasively that Franco’s forces murdered Sunyol not because he was Barça’s president “but because he accidentally crossed the front line and represented the Republic.” The story of Madrid’s president during the war, Rafael Sánchez Guerra, “a democrat, a liberal . . . committed to the Republic” (p. 39) arrested and tried by the Franco regime, serves as a useful counterpoint to the better known role of Santiago Bernabeu, the right-wing patriarch of Real Madrid during the Franco era.

The 1950s, the book shows, were a golden era for both the clubs and the rivalry itself. With the construction of Bernabeu stadium and Camp Nou, Barça and Madrid had grandiose stages for the performances of their newly arrived superstars: László Kubala (Hungary) and Alfredo Di Stéfano (Argentina), respectively. Camp Nou was the “House that László Built” (see pp. 97, 102-03) and his team’s wonderful success at the time motivated Bernabeu to sign Di Stefano. One of the book’s revelations, based on fascinating hard evidence, is the extent to which Barça’s dithering and doubt, as much as pressure from the Franco regime, led Di Stefano to Madrid. This was a crucial episode in the making of the rivalry as the Blond Arrow’s Dream Team (Puskas, Gento, Kopa, Del Sol, Santamaria . . .) went on to win the first five European Cups!

After Barcelona knocked Madrid out of the 1960-61 European Cup, the rivalry entered a “dark era” that ended with the arrival of Johan Cruyff on the eve of the Franco regime’s demise. The long 1960s are remembered for Real Madrid becoming cultural ambassadors of the dictatorship (though players had little choice in this) as well as for the infamous Copa del Generalissimo quarterfinal of 1970 when referee José Guruceta gifted visiting Madrid a penalty that eliminated the hosts. Guruceta’s match report describes 30,000 cushions thrown on to the pitch; his name, Lowe writes, “became Catalan shorthand for every referee in Spain, shorthand for injustice. For some, he had become shorthand for the football authorities, for Real Madrid and for the dictatorship” (p. 211).

The second half of the book opens with Johan Cruyff’s explosive impact at the Camp Nou in 1973-74. Cruyff’s debut coincided with the appearance of Barca’s slogan “mes que un club” (“More than a club”, now trademarked), which the book notes “did not feel entirely coincidental, football, politics and culture converging” (p. 232). Madrid’s response to the Cruyff-ication of Barca came in the 1980s with the Quinta del Buitre, which succeeded in resurrecting Real’s reputation but failed to win back the trophy that most defines the club: the European Cup.

The final third of the book covers the period from the 1990s to the present. It focuses on how and why Barcelona and Madrid came to dominate European football after 1998. This part is written in a markedly more journalistic style and is less original in its analysis. It is always more difficult for historians to write about contemporary events and avid readers have benefited from English-language books by Phil Ball and Jimmy Burns, among others. Last but not least, the satellite and Internet revolution has made it possible for many of us to closely follow the clásico’s recent history, on and off the pitch. Still, the 406-page book saves some juicy insights for the very end as it considers the impact of the Galacticos, the Special One, the cantera vs. cartera approaches to developing young players (training them vs. buying them), as well as how Spain’s international success has changed both the Barcelona vs. Real Madrid rivalry and fans’ sense of nationhood.

With our memories of Barcelona’s operatic 4-3 comeback victory at the Bernabeu on Sunday still fresh and raw, let us not give in too readily to melancholy or nostalgia. As the closing passage of Fear and Loathing in La Liga puts it: “Real Madrid and Barcelona FC will meet again and when they do the cast will be the most impressive in the game, tickets will sell out in hours and millions will gather in front of television screens across the world, more than for any other club match anywhere. And on the morning of the game they will still be there, clutching flowers, pleading for victory. Once more into the fray. Life in ninety minutes” (p. 409).

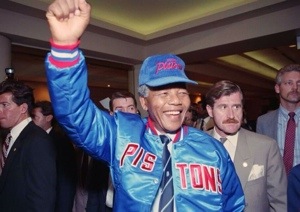

Sport is serious fun. Nelson Mandela, a keen amateur boxer in his youth, appreciated how the antiapartheid sport boycott assisted South Africa’s liberation struggle and, as a democratically elected president, he used the “politics of pleasure” to propel Rainbow Nationalism. Team sports like football reveal much about the experiences and mindsets of neighborhoods, cities, and nations. “The way we play the game, organize it and reward it reflects the kind of community we are,” is how Arthur Hopcraft put it in The Football Man (1968), one of the finest football books ever written.

Sport is serious fun. Nelson Mandela, a keen amateur boxer in his youth, appreciated how the antiapartheid sport boycott assisted South Africa’s liberation struggle and, as a democratically elected president, he used the “politics of pleasure” to propel Rainbow Nationalism. Team sports like football reveal much about the experiences and mindsets of neighborhoods, cities, and nations. “The way we play the game, organize it and reward it reflects the kind of community we are,” is how Arthur Hopcraft put it in The Football Man (1968), one of the finest football books ever written.

These issues strike at the heart of a new project I am embarking on with my Latin Americanist colleague Brenda Elsey, author of a splendid book on fútbol and politics in Chile. Brenda and I will be editing a special issue of Radical History Review on “Historicizing the Politics and Pleasure of Sport.” This marks the first time RHR, an academic journal known for “addressing issues of gender, race, sexuality, imperialism, and class, and stretching the boundaries of historical analysis to explore Western and non-Western histories” will turn its attention to sport. The issue is scheduled for publication in 2016.

Here’s the call for papers:

The global reach of football (soccer), basketball, cricket, and Olympic sports in the contemporary world can be traced back to European and U.S. imperial and commercial expansion. The agents of that imperialism—teachers, soldiers, traders, and colonial officials— believed sport to be an important part of their “civilizing mission.” Military interventions in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, often accompanied by “soft power” cultural programs and private business ventures, fueled the popularity of Western sports. Reform movements tied eugenics and racism to their dissemination. But local elites and subalterns were not simply duped; they enjoyed the games on their own terms. As more communities participated, sport came to represent and constitute broader processes of social change. In the stands, sports pages, and clubhouses, fans rendered sport a place to debate racial and gender hierarchies. In the late twentieth century, international sport became part of a new global capitalist network of sport institutions (e.g. FIFA, International Olympic Committee, International Cricket Council), private corporations, mass media, and migrant athletes and coaches. In this process, sport came to symbolize and intensify unequal social and economic relations.

Histories of sport reveal a paradox: sport generates empowerment and disempowerment; inclusion and exclusion; unity and division. Sports have provided spaces for pleasure, freedom, solidarity, and resistance, but they have also reproduced class privilege, patriarchy, and racism. The performance of masculinities, creation of ideal body types, and the ongoing marginalization of women in sport illustrate these tensions. Recent events in Brazil, where controversy over contemporary mega sporting events merged with massive demonstrations for a range of social justice issues, highlight the unusual capacity of sport both to crystallize inequalities and to trigger civic activism. Reports of labor abuses in Qatar and censorship and environmental damage in Russia cast a dark shadow on the human and material costs of hosting “mega” sports events.

The editors invite submissions from scholars working on any period and world region. We are especially interested in studies that build upon the rich historiography about the nature of agency, identity, and embodiment as a way to explore sport’s contradictory past and present.

Football and Independence in Zambia

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

Guest Post by *Hikabwa Chipande

LUSAKA—On a rainy Friday evening at the Pamodzi Hotel, Zambia Open University Professor Ackson Kanduza, president of the Southern African Historical Society, convened a forum based on my paper “Football and Independence in Zambia: A Political and Social History 1950s-1964.”

Part of my doctoral research on colonial and postcolonial Zambian football, the paper draws on archival, newspaper, and oral sources to argue that the changing culture of the African game influenced the anti-colonial nationalist struggle by fighting racial segregation and promoting African leaders to highly visible and prestigious administrative positions before independence.

In the early 1960s, colonial racism in then-Northern Rhodesia was still intense. Segregation kept Africans out of European-owned shops and forced black customers to shop through a window instead; Africans were not allowed to enter whites-only train carriages and buses; and jobs paying higher wages were reserved for whites.

But in 1961-62, black and liberal white businessmen founded the nonracial (racially mixed) National Football League. A black man, Tom Mtine, was named chairman of an otherwise white-dominated league executive. Two years prior to independence, the NFL permitted black players to be on the same teams as whites, and Africans were also allowed to represent the territory in international competitions. The emergence of black administrators like Tom Mtine and the game’s function as a “neutral” cultural form among people speaking 73 languages helped to assert black power as well as a sense of Zambian-ness that cannot be ignored in the history of Zambia.

An audience of both academics and members of the general public posed interesting questions and offered constructive comments. Most participants agreed with me that these sporting events signified an important step towards political freedom. Some noted that as Zambians celebrated their country’s 40th independence anniversary, my historical evidence about black leaders in football and the hosting of an international football tournament in 1964 to celebrate the nation’s birth would be highly appreciated by millions of Zambians. The discussion also grappled with the seemingly contradictory evidence that the British believed the game to be part of the “white man’s burden” while local people used it to fight colonial oppression.

“I did not know that our football has such a rich history,” said Pride Mwaanga; “I was wondering about the connection between football and independence, but now it makes sense!” Other participants asked why this rich history of Zambian football has not yet been explored. Echoing the conclusions of Marissa Moorman’s recent history of music and nationhood in the musseques (shantytowns) of colonial Luanda, Angola, audience members highlighted how, unlike anti-colonial political leaders, Zambian football administrators and players’ contributions to building the Zambian nation are not recognized in typical historical accounts.

Participants also stressed the need to publish biographies of past footballing greats such as “Ucar” Godfrey Chitalu, Dickson Makwaza, John “Ginger” Pensulo and many, many others. Professor Moses Musonda, Zambia Open University Deputy Vice Chancellor, pointed out that we need more scholars to research and write the history of football in Zambia, otherwise we are going to lose this valuable past.

Other interesting contributions came from Mrs. Kanduza and, again, from Prof. Musonda, who both gave testimonies of how they experienced leisure activities in welfare centers during the colonial era. These social centers played a critical role in the development of football. Prof. Musonda stated that Europeans enforced separate social institutions such as welfare halls to make sure that young Africans did not have the opportunity to challenge young Europeans in sport. Ironically, the same welfare centers and sporting facilities helped African men and women build their self-esteem and were later turned into avenues for political agitation.

Prof. Kanduza concluded the event by pointing out that a goal of the Zambia Open University is to organize forums that give opportunities to listen to unheard local voices. He highlighted how the research and discussion of “Football and Independence in Zambia” captures voices and conveys the historical experiences of African people through the prism of sport. The evening ended with a promise to organize more of these lively and insightful sessions in the near future.

—

*Hikabwa Chipande is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at Michigan State University. He is currently in Lusaka researching the social, cultural and political history of football in colonial and postcolonial Zambia. Follow him on Twitter at @hikabwachipande