Barcelona, 5 July 1982: Paolo Rossi had just headed in an Antonio Cabrini cross to put us up 1-0 against Brazil in the last game of the second group stage of the 1982 World Cup. My friend Fabio and I, football-obsessed youngsters, sat wide-eyed on the floor of an impossibly crowded living room in a relative’s home outside Pesaro, in the hills of the Marche region of Italy. A few days before we had been part of a spontaneous street carnival with tens of thousands of fellow Romans celebrating our victory against Maradona’s Argentina. Rossi’s goal suddenly made a miracle possible: beat Brazil and earn a place in the semifinals.

Five minutes later, a Brazilian Doctor made an incision that surgically removed the optimism of hope. Socrates, we knew from watching Corinthians games on Teleroma 56 (a local station), had a penchant for embarrassing defenders with graceful pivots on the ball and elegant heel passes. To say nothing of goalkeepers humiliated by his swerving free kicks and shots from impossible angles.

That hot July afternoon on the pitch of Español’s Sarria Stadium, Socrates received the ball in midfield, carried, dished it off to Zico and continued his run forward. With the outside of his right foot, Zico quickly sliced a delightful pass to a streaking Socrates in the box. Socrates took a simple touch and appeared to be running out of room on the right side of the 6-yard box. Where most players would square the ball back into the middle of the box for a teammate to run on and strike at goal, Socrates instead took a precise near-post shot that faked Dino Zoff out of his shorts: 1-1. No! He didn’t just do that?! Watch it here. (Italy went on to win the game 3-2 and the World Cup.)

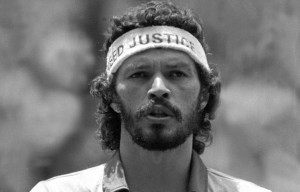

After the 1982 tournament, Corinthians traded Socrates to Fiorentina so we got to appreciate the fullness of this grandiose footballer for many years. Even Juve fans like me, whose contempt for La Viola is unrestrained, became fond of “Tacco d’Oro” — the Golden Heel — the tall, lanky, bearded midfielder with the long curly hair who added so much spectacle to Serie A in the age of Maradona, Platini, and Falcao.

A decade later, I found myself still learning from Socrates but in a completely different context. While teaching one of the first undergraduate courses on soccer ever taught in an American university, my students and I discussed Socrates’s role in Corinthians Democracy, a movement that helped propel democratic change in Brazil in the early 1980s. How many professional athletes would threaten to retire, as Socrates did in 1982, if a conservative businessman were to take the reins of a popular team?

So it was with profound sadness that I learned of Socrates’s passing at the age of 57. The official cause of death was “septic shock from an intestinal infection” according to a São Paulo hospital statement. Like Garrincha, Brazil’s most loved footballer, Socrates was an alcoholic. The rum-like cachaça had become his vital fluid. As Socrates candidly put it in an interview: “This country drinks more cachaça than any other in the world, and it seems like I myself drink it all.” We all battle our demons.

As the South Africans say, “Hamba kahle” brother Socrates. Your love of the game and commitment to social justice will never be forgotten.

Suggested reading:

Matthew Shirts, “Socrates, Corinthians, and Questions of Democracy and Citizenship,” in Joseph Arbena, ed., Sport and Society in Latin America: Diffusion, Dependency, and the Rise of Mass Culture (New York: Greenwood Press, 1988), pp. 97-112.

Simon Romero’s poignant obituary of Socrates in the New York Times is here.