Guest Post by Khaya Sibeko (@KhayaSibeko1)

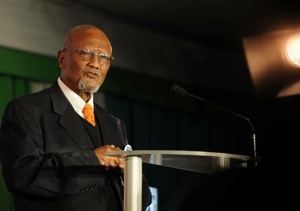

JOHANNESBURG—On October 30, 2013, Leepile Taunyane, South Africa’s legendary football administrator, died at the age of 85. It would not be an exaggeration to compare his passing to the burning of a national archive.

Born in Alexandra, Johannesburg, Taunyane grew up playing football in the streets and then joined Rangers in the early 1950s, a club known for its technical prowess and feared for its lineup stacked with ex-convicts. After hanging up his boots, in the 1960s Taunyane started a career as a football organizer and served as principal first at Alexandra High School and then at Katlehong High.

His administrative career saw him involved in every major transformation in the South African game. Taunyane worked with Bethuel Morolo at the South African Bantu Football Association and then with his successor, George Thabe. In the mid-1980s, an era of massive political and social upheaval in apartheid South Africa, Taunyane led the Transvaal affiliate of Thabe’s Africans-only organization to throw its weight behind the National Soccer League. A precursor of today’s Premier Soccer League, the NSL was a new, racially integrated league launched in 1985 as a break away league from Thabe’s NPSL. Taunyane became the NSL’s first president.

In a recent City Press article, Premier Soccer League and Orlando Pirates chairperson, Irvin Khoza honored his mentor: “I was his student when he was a teacher. He recruited me at the tender age of 14 to become a member of the Alexandra Football Association. We later rubbed shoulders in the national league and federation structures. Dr. Taunyane personifies the values that govern my decision-making and actions, consciously and unconsciously.”

Taunyane was “the last of the Mohicans” of football administrators of a venerable generation. Even when others around him found the temptations of post-isolation football too much to resist, Taunyane remained a diligent and incorruptible servant of the beautiful game. It was no surprise when, a few years ago, the PSL bestowed the honorific title of Life President.

It is not enough to celebrate and award titles, of course. By publicly recognizing Taunyane’s great legacy, local football administrators should strive to follow his exemplary managerial conduct. That would be the best way to remember and honor a “son of the soil” who spared neither time nor energy in the service of football and education.

Undoubtedly, the gods of South African football have placed Taunyane alongside Bethuel Mokgosinyane, Solomon Senaoane, Dan Twala, Albert Luthuli, Henry Ngwenya, George Singh and so many elders of the distant past, men whose efforts shaped our football in the era of segregation and apartheid. Without the contributions of men like Taunyane, South Africa would never have hosted the 2010 World Cup and the PSL would not be among the ten richest leagues in the world.

Tag: South Africa

Guest Post by *Liz Timbs

In Zulu culture, an imbiza is a large ceramic pot used for brewing utshwala (sorghum beer). This vessel enables the fermentation of a fluid that facilitates communication with the amadlozi (ancestors) and lubricates social interactions. Taking my cue from this vernacular technology, I am launching Imbiza: A Digital Repository of 2010 World Cup Stadiums and Fan Parks—an open access collection of primary sources for brewing ideas and encouraging public dialogue about this defining event in South Africa after apartheid.

The potential for this digital project crystallized during a recent session of the Football Scholars Forum on Alegi and Bolsmann’s new book Africa’s World Cup: Critical Reflections on Play, Patriotism, Spectatorship, and Space. During the online discussion, the conversation turned to ways of integrating academically-oriented essays like those in Africa’s World Cup with web-based images, videos, and texts produced by non-specialists for a general audience.

While this idea was initially framed in terms of what could be done for next year’s World Cup in Brazil, the historian in me started thinking about how a project like this could help further understand the 2010 World Cup. Serendipitously, I was also searching for a suitably interesting project to fulfill the requirements of my Cultural Heritage Informatics Fellowship, a program run by Dr. Ethan Watrall at Michigan State University in collaboration with MATRIX, the digital humanities and social sciences center. After some more pondering and a chat with Peter Alegi, my PhD supervisor (and curator of this blog), I decided to go for it.

In building the Imbiza repository, I aim to integrate openly accessible texts, images, sounds, and videos that capture fans’ perspectives and experiences at World Cup stadiums and fan parks. I’ve already begun to collect materials, so accumulating enough sources surely will not be an issue. Among the main challenges for the project will be organizing, tagging, and presenting the items in an accessible, informed, and compelling manner. My hope is that this project will build a model that can be replicated in the study of future World Cups and mega-events, allowing for critical engagement as well as nostalgic reflection.

I do not want this to be a solitary academic venture; that would get away from the whole point of it. I want Imbiza to stand as a testament to the potential of digital technologies for collaborative knowledge production. I am limited by geography, time, and finances in building this archive from my base in East Lansing, but digital platforms, like this one, can get around some of these obstacles.

So consider this blog post a call; a call for submissions, ideas, and inspiration to make Imbiza a success. With the 2014 World Cup in Brazil just a few months away, the time is now to reflect on the legacies of the 2010 World Cup. Ke nako!

—

Follow this project’s progress on Twitter via the hashtag #Imbiza and on the project blog. If you have comments, submissions, sources, or questions, please contact me at imbizaarchive AT gmail.com.

*Liz Timbs is a PhD student in African history at Michigan State University. Her research interests are in the history of health and healing in South Africa; masculinity studies; and comparative studies between South Africa and the United States. Follow her on Twitter: @tizlimbs.

Guest Post by *Liz Timbs

In August 2013, I had the privilege of spending three days with the Izichwe Football Club in Pietermaritzburg, capital of South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province. During my brief stay, I observed training sessions, visited players’ high schools, and interviewed some of the young men and coaches. The quotes below come from these conversations.

Every weekday afternoon at the University of KwaZulu-Natal campus in Pietermaritzburg, two dozen 10th grade-boys come together on a humble football pitch to hone their skills at Izichwe Football Club. Established in 2010 and named after the first military regiment (ibutho) commanded by Shaka Zulu, the club is “not just about kicking a ball,” says Thabo Dladla, founding director of Izichwe and Director of Soccer at UKZN. It is also about developing young men of character and respect who represent their communities and themselves with pride and honor.

Respect (inhlonipho in the Zulu language) and discipline (inkuliso) are core values at Izichwe as they are in Zulu culture more broadly. The coaches refer to the teenagers as amadoda (umarried young men) and even baba (father) to stress the importance of carrying themselves in a mature way on and off the pitch.

These two dozen high school boys at Izichwe embody the values and lessons imparted to them by their coaches, especially Thabo’s emphasis on showing self-respect as much as respect for others. When I spoke with the youngsters, they politely thanked me for coming to Pietermaritzburg to meet them and spoke with poise beyond their years.

“The program is not only about sports or soccer. It’s mostly about life,” Asanda tells me. Izichwe is “about respecting the people you are around, and playing fair, which applies in life. You do it the right way. Don’t cheat. Don’t cheat yourself.” Similarly, Simphiwe stated, without hesitation, that Izichwe had taught him “to work hard in life and to respect your instructors.” Asanda and Simphiwe’s statements were echoed in a team meeting I observed. Technical director Mhlanga Madondo, a police officer, entreated the players to look at their performances in the previous weekend’s tournament, stating that he expected them to “take responsibility for their own growth.”

“The program is not only about sports or soccer. It’s mostly about life,” Asanda tells me. Izichwe is “about respecting the people you are around, and playing fair, which applies in life. You do it the right way. Don’t cheat. Don’t cheat yourself.” Similarly, Simphiwe stated, without hesitation, that Izichwe had taught him “to work hard in life and to respect your instructors.” Asanda and Simphiwe’s statements were echoed in a team meeting I observed. Technical director Mhlanga Madondo, a police officer, entreated the players to look at their performances in the previous weekend’s tournament, stating that he expected them to “take responsibility for their own growth.”

Hard work is another crucial component of the Izichwe way. When I asked Lindi what the program had given him, he said, simply: “discipline.” Every day, without exception, the boys make their way to the university sports fields to train from 3:30p.m. to 5:30p.m. Many of the boys also play for their school teams at least one day a week (with one boy competing in cross country events in addition to playing school soccer). Saturday is match day in a local amateur league. Sundays are reserved for tournaments. This intense, demanding schedule instills in the boys not only physical endurance and strength, but mental acuity as well. Dladla believes this constant pressure shows the dedication and perseverance of his players. “Boys like Siphesehle (the cross country runner), he’s very, very competitive, you know? He did cross country; he came [to training], and I said, “Hey! You rest!” He said, “No, coach! I came to train!”

Although the players’ development as athletes is central to the program, Thabo, a former teacher and ex-professional footballer, regularly reminds players that “nothing in this life is as important as knowledge.” As a result, the program integrates numerous educational programs into their activities. Every night at the conclusion of practice, around 5:30, a group of the players gathers in a classroom on campus to study under the supervision of volunteer university students.

Although the players’ development as athletes is central to the program, Thabo, a former teacher and ex-professional footballer, regularly reminds players that “nothing in this life is as important as knowledge.” As a result, the program integrates numerous educational programs into their activities. Every night at the conclusion of practice, around 5:30, a group of the players gathers in a classroom on campus to study under the supervision of volunteer university students.

The coaches closely monitor individuals’ academic performance by reviewing school progress reports. This scrutiny, one parent explained, helps to “notice any hiccups in their progress at school.” In the opinion of Devon, the life sciences teacher at Alexandra High School, which several Izichwe boys attend, such devoted attention to player’s academics is unusual when compared with many other students who lack such careful supervision. “It’s a structured lifestyle which, I think, is lacking in a lot of our schools,” Devon explained. “I think that’s partly why these boys are so successful. They grow and they excel in every area.”

The youngsters openly expressed their gratitude to the adults who put precious time, energy, and resources into the program. “There are many kids out there who want this opportunity and we are very special to get that,” Mpumelelo said. Sandile stated unequivocally that the program has “changed the most part of my life.” Keelyn agreed, and without hesitation added that thanks to Izichwe, “I found myself.” Sandile spoke passionately about his appreciation for Izichwe: “Basically, what this program means to me is that it gives me the opportunity to realize a dream that I never thought . . . it was never something I believed I’d be able to do . . . it just made me realize, if I continue working hard enough, I can be one of the best players in the world.”

The youngsters openly expressed their gratitude to the adults who put precious time, energy, and resources into the program. “There are many kids out there who want this opportunity and we are very special to get that,” Mpumelelo said. Sandile stated unequivocally that the program has “changed the most part of my life.” Keelyn agreed, and without hesitation added that thanks to Izichwe, “I found myself.” Sandile spoke passionately about his appreciation for Izichwe: “Basically, what this program means to me is that it gives me the opportunity to realize a dream that I never thought . . . it was never something I believed I’d be able to do . . . it just made me realize, if I continue working hard enough, I can be one of the best players in the world.”

The Izichwe coaches are also grateful to be part of this project. Coach Madondo said that working with these young men has inspired him; he’s seen them “not just growing physically, but also [in] how to approach life.” Coach Ronnie “Reese” Chetty, who had a long coaching career including experiences in the United States, told me he is reinvigorated by the hard work and dedication these young men exhibit on a daily basis. The coaches are also driven and guided by the hardships, struggles, and perseverance of some of the players and families.

“It’s people like Sipesehle and Mhlengi’s mothers who sometimes give me lots of motivation when I see how hard they try, you know?” explained Thabo Dladla. “So then, I say: ‘Hey man! I cannot give up. I cannot let them down. So let me try and help them develop real men,’ you know?”

And from what I saw these Izichwe boys are becoming real men of immense diligence, humility, discipline, and respect. And, perhaps even more so, this community of boys, men, and parents demonstrates the great potential for grassroots soccer programs to fuel the development of not only athletic talent with a bright future in sport, but also of productive citizens in a democratic society.

—

*Liz Timbs is a PhD student in African history at Michigan State University. Her research interests are in the history of health and healing in South Africa; the professionalization of medicine; masculinity studies; and comparative studies between South Africa and the United States. Follow her on Twitter: @tizlimbs

By Bruce Berglund (cross-posted from @NewBookSports)

By Bruce Berglund (cross-posted from @NewBookSports)

In 2010, for the first time, an African nation hosted the FIFA World Cup. The advertisements surrounding the tournament used graphics and sounds intended to conjure the image of a vibrant, exotic land. In fact, though, the African-ness of the South African World Cup was pretty thin, when not wholly fabricated. For example, the music that introduced ESPN’s World Cup coverage sounded very African, as it opened with the sounding of an ox horn (the promo showed a bare-chested tribesman blowing the horn atop a mountain, silhouetted against the setting sun) and then built with pulsing drums and a choir singing layered refrains. But the piece had been written by a composer from Utah, the musicians had recorded it in Utah, and the choir consisted of members of the Broadway cast of The Lion King. At least Shakira’s ubiquitous song “Waka Waka (This Time for Africa)” had a more substantial African connection. It had been lifted, initially without credit, from a Cameroonian military song made popular in the 1980s by the group Golden Sounds.

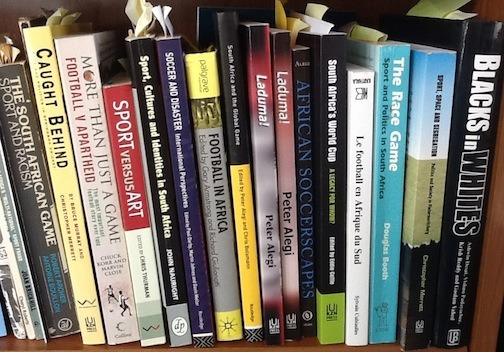

The ironies of the 2010 tournament in South Africa are revealed in a number of essays in Africa’s World Cup: Critical Reflections on Play, Patriotism, Spectatorship, and Space (University of Michigan Press, 2013), edited by Peter Alegi and Chris Bolsmann. In the interview with Peter, we learn of the findings and observations of the volume’s contributors: an international collection of anthropologists, architectural critics, bloggers, geographers, sociologists, journalists, photographers, and former players who all attended matches in South Africa. They make sharp criticisms of class divides at the venues, the nationalism and commercialism, and, of course, the imperial reach of FIFA. But as we hear from Peter, the book’s authors were also fans. When mixing with other fans outside the stadiums, and then cheering their teams when the matches began, even normally skeptical academics and journalists were caught up in the event. Their experiences show that, for all its faults, the FIFA World Cup is still an incomparable event.

Click here to download the mp3 of the interview.

Guest Post by *Marc Fletcher

Gloomy skies and wet weather greeted the Research Forum on South African Football held at the University of Johannesburg (UJ) last month. The bleak conditions made for an intimate crowd, but the academics, journalists and sports practitioners in attendance were rewarded with three strikingly different presentations on varying aspects of the “beautiful game” in South Africa. The aim of the forum was to advance the specialized study of soccer in the country and beyond.

First up was Chris Bolsmann, a South African sociologist based at Aston University, Birmingham. His paper entitled “Professional Football in Apartheid South Africa: Leisure, Consumption and Identity in the National Football League, 1959-1977” provided a rich history of the whites-only National Football League (NFL) during apartheid. The common misconception of South African football is that it has historically been, and continues to be, an exclusively black, working-class game. Yet, Chris’s work challenges such a perception and begins to reconstruct a past that is often forgotten or even ignored. Matches in this white league were staged in front of segregated crowds. A successful corporate affair, the NFL attracted a host of world-renowned players, including George Best and Bobby Charlton. In concluding that the NFL became the leisure and sporting entertainment of choice for significant numbers of white and black (particularly Indian and Coloured) South Africans, this history emphasized how football in South Africa has had a more diverse support base than is often acknowledged.

First up was Chris Bolsmann, a South African sociologist based at Aston University, Birmingham. His paper entitled “Professional Football in Apartheid South Africa: Leisure, Consumption and Identity in the National Football League, 1959-1977” provided a rich history of the whites-only National Football League (NFL) during apartheid. The common misconception of South African football is that it has historically been, and continues to be, an exclusively black, working-class game. Yet, Chris’s work challenges such a perception and begins to reconstruct a past that is often forgotten or even ignored. Matches in this white league were staged in front of segregated crowds. A successful corporate affair, the NFL attracted a host of world-renowned players, including George Best and Bobby Charlton. In concluding that the NFL became the leisure and sporting entertainment of choice for significant numbers of white and black (particularly Indian and Coloured) South Africans, this history emphasized how football in South Africa has had a more diverse support base than is often acknowledged.

My paper on “Divisions, Difference and Encounters in Johannesburg Soccer Fandom,” explored contemporary cultures of fandom beset by race and class divisions, where domestic football is regularly constructed as an Africanized space without white supporters. However, through an ethnography of Kaizer Chiefs, Bidvest Wits, and Manchester United supporters’ clubs in Johannesburg, I began to explore the deeper complexities, where supporters on the margins of these groups began to engage with the other. In doing so, some fans challenged these social barriers in football and thus reinterpreted their understanding of soccer fandom and their wider experiences of everyday life in the city.

My paper on “Divisions, Difference and Encounters in Johannesburg Soccer Fandom,” explored contemporary cultures of fandom beset by race and class divisions, where domestic football is regularly constructed as an Africanized space without white supporters. However, through an ethnography of Kaizer Chiefs, Bidvest Wits, and Manchester United supporters’ clubs in Johannesburg, I began to explore the deeper complexities, where supporters on the margins of these groups began to engage with the other. In doing so, some fans challenged these social barriers in football and thus reinterpreted their understanding of soccer fandom and their wider experiences of everyday life in the city.

Chris Fortuin, based in the Department of Sport and Movement Studies at UJ, gave the third paper–an eye-opening account of the grim state of youth development in South African football. It was alarming to hear the inadequate ratio of qualified youth coaches to players in South Africa compared to some of the giants of international soccer, especially Spain. The shortage of such coaches, along with the absence of a coherent development plan at the national level, is harming the game at all levels and has contributed to the malaise of the men’s national team, Bafana Bafana.

Chris Fortuin, based in the Department of Sport and Movement Studies at UJ, gave the third paper–an eye-opening account of the grim state of youth development in South African football. It was alarming to hear the inadequate ratio of qualified youth coaches to players in South Africa compared to some of the giants of international soccer, especially Spain. The shortage of such coaches, along with the absence of a coherent development plan at the national level, is harming the game at all levels and has contributed to the malaise of the men’s national team, Bafana Bafana.

The presentations encouraged members of the audience to think more seriously about football as an academic field of inquiry. During the second half of the forum panelists responded to numerous questions from the floor. One question stuck out, one that is often asked; why are black South Africans not writing about this subject? It is true that much of what is written on the subject is by foreigners like me. But a main goal of football scholars, regardless of origin, is to empower South African students in the humanities and social sciences (and other fields) with tools and desire to critically engage with football studies.

With questions on the presentations filling up the second half, the question of where does the academic study of South African football go from here was left unresolved. Events such as the UJ forum can play a vital role in motivating South African scholars to research and write about their game. Clearly, football is a legitimate and fascinating area of research. But many more events like the forum are needed to further develop the field and chart future directions.

To this end, readers of this blog who are in the Johannesburg area, are welcome to attend the UJ Wednesday Seminar Series on Wednesday, May 8, at 3:30pm, where I will be presenting a paper entitled “Reinforcing Divisions and Blurring Boundaries: Race, Identity and the Contradictions of Johannesburg Soccer Fandom.” For details about the event click here.

The journey continues.

*Marc Fletcher, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Johannesburg, blogs at One Man and His Football: Tales of the Global Game. Follow him on Twitter: @MarcFletcher1

Guest Post by Marc Fletcher* (cross-posted with permission of Africa is a Country and the author.)

One of the key sights of this year’s Africa Cup of Nations has been emptiness. Aside from the opener between South Africa and Cape Verde, the television cameras have picked up images of large swathes of empty seats. Whether it was Burkina Faso’s last gasp equalizer against Nigeria in Nelspruit or Tunisia’s equally late winner versus Algeria in Rustenburg, the empty seats appeared to outnumber the fans that had made the trip. Coverage from previous editions of the tournament in Ghana, Angola and Equatorial Guinea picked up similar images. This is clearly not a South African-only problem.

I had earlier hoped that the more reasonable pricing structure for this tournament as opposed to the 2010 World Cup would have made the games more accessible to majority of poorer, working class football fans; those who make up the vast majority of the support base of South Africa’s domestic clubs. The empty seats suggest that it’s reaching few people in general.

So what are the issues behind this?

Firstly, there aren’t many players in this tournament that can be described as superstars. In the World Cup, there was Messi, Ronaldo and the entire Spanish squad. This time around, there’s Didier Drogba, whose career is winding down in China but few others. Yes, there are players such as Yaya Touré and Asamoah Gyan but they simply do not have the same star status. Why spend hard-earned money to watch two teams that you have little or no interest in?

Secondly, the 5 pm kick off times are hardly conducive to getting bums on seats. As I write this, I have one eye on the Bafana v Angola match. While attendance seems to be significantly greater than in most of the other matches, there are still many empty seats. Traffic at this time in the major cities can be nightmarish and some fans will be unwilling to put themselves through the gridlock and confusion. To make sure that you get to the stadium in plenty of time means taking the afternoon off work.

A big contributory factor is that that there are few, if any African countries that have a large fan base with a large enough disposable income to fly out to the southern tip of the continent for the tournament. Unlike the vast hoards of traveling football tourists at the Euros or at the World Cup, the support of visiting teams is usually restricted to a small rump of die-hard regular fans who are sometimes subsided by the state or political parties. While the commitment on the part of these fans is impressive, this is not going to fill these former World Cup venue. This is a problem that is not going to go away anytime soon.

But the thing that strikes me most as I write from Johannesburg is the absence of evidence that the tournament is taking place. In 2010, there were numerous posters around the city, large fan parks with big screens and people blowing vuvuzelas on street corners. Thousands crammed onto the streets in the north of the city when Bafana went on an open-top bus tour while a giant photo of Cristiano Ronaldo was emblazoned on Nelson Mandela Bridge. This time, it is severely underwhelming. There is no party atmosphere, no fan parks, little hype on local television or radio. Bafana shirts are far less apparent on the street in contrast to 2010. It’s not totally absent though. Staff at my local Spar were wearing their Bafana shirts today, while bar staff on Soweto’s tourist strip on Vilakazi Street were doing the same.

Still, it’s as if the tournament has passed Jo’burg by and I wouldn’t be surprised if it passes most of South Africa by with little more than a passing awareness that Africa’s biggest football tournament is in their country. The slogan of the tournament is “The beat at Africa’s feet,” but this beat is strangely subdued.

Maybe people realize that they have more important things to do than watch football?

N.B. During the South Africa vs Angola match, Moses Mabhida stadium in Durban seemed to be fuller in the second half. The commentator on Supersport (the South African satellite channel that dominates football broadcasting on the continent) has suggested that there is an excessive number of security cordons, which has delayed many fans from getting into the ground until the latter part of the first half.

* Marc Fletcher (MarcFletcher1), a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Johannesburg, blogs at One Man and His Football: Tales of the Global Game.

These are interesting times for politics and football in South Africa. The African National Congress is meeting this week in Bloemfontein/Mangaung to select the ruling party’s new leaders while 94-year-old Nelson Mandela is still hospitalized recovering from surgery and a lung infection. Domestic football has been rocked by a FIFA match fixing report alleging that a transnational match-fixing syndicate based in Singapore, assisted by South African Football Association (SAFA) officials, fixed Bafana Bafana’s friendlies against Thailand, Bulgaria, Colombia and Guatemala in the build up to the 2010 World Cup. Five SAFA men, including its president, Kirsten Nematandani (in photo above), have been suspended pending “further examination” of possible “criminal intent in collusion” with a front organization set up by the convicted match fixer Wilson Raj Perumal.

These are interesting times for politics and football in South Africa. The African National Congress is meeting this week in Bloemfontein/Mangaung to select the ruling party’s new leaders while 94-year-old Nelson Mandela is still hospitalized recovering from surgery and a lung infection. Domestic football has been rocked by a FIFA match fixing report alleging that a transnational match-fixing syndicate based in Singapore, assisted by South African Football Association (SAFA) officials, fixed Bafana Bafana’s friendlies against Thailand, Bulgaria, Colombia and Guatemala in the build up to the 2010 World Cup. Five SAFA men, including its president, Kirsten Nematandani (in photo above), have been suspended pending “further examination” of possible “criminal intent in collusion” with a front organization set up by the convicted match fixer Wilson Raj Perumal.

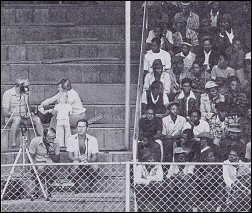

Consumed by the details of this latest sporting malfeasance as well as the tensions in ANC politics at a particularly difficult moment for South Africa, I was stunned to belatedly learn of the death of Sedick Isaacs at the age of 72. I had the extraordinary privilege to meet him in 2010 while a Fulbright Scholar at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN). I was humbled and honored to share the stage with Isaacs in a symposium on football history held on the UKZN Westville campus and sponsored by the German cultural exchange program, DAAD.

Isaacs spoke matter-of-factly about the cruelty and hardships endured during his 13 years on Robben Island. What had earned him a place in apartheid’s most notorious prison had been his role as saboteur in the armed struggle. Standing before us wearing a blue sweater in the humidity of sub-tropical Durban, Isaacs pointed out that his years on Robben Island had left him always feeling cold regardless of the temperature. A point he reiterated in Cape Town two weeks later when he spoke at my book launch for African Soccerscapes. (That’s us in the photo below.)

By studying and playing on Robben Island, Isaacs told us, prisoners formed and maintained communities of survival and resistance. He earned a university degree while behind bars and also helped to build and administer the prisoners’ Makana Football Association. (The story is admirably told by Chuck Korr and Marvin Close in More Than Just a Game: Football v Apartheid.) When the prisoners finally secured the warden’s approval for their league after three years of struggle, Isaacs ended up handling much of the day-to-day operations of the Makana FA.

Dr. Isaacs explained that the weekly cycle of matches proved crucial in fighting “eventless time” — a debilitating condition for prisoners serving lengthy sentences. The cycle worked something like this: teams started the week by analyzing the previous match and then by midweek there was growing anticipation for upcoming matches. Conversations, banter, and meetings stoked the hype and created heroes and personalities. By the weekend, excitement surrounding the matches reached fever pitch. Football’s importance, Isaacs said, was enhanced by its force as a provider of human emotions in an emotionally neutral context.

Dr. Isaacs explained that the weekly cycle of matches proved crucial in fighting “eventless time” — a debilitating condition for prisoners serving lengthy sentences. The cycle worked something like this: teams started the week by analyzing the previous match and then by midweek there was growing anticipation for upcoming matches. Conversations, banter, and meetings stoked the hype and created heroes and personalities. By the weekend, excitement surrounding the matches reached fever pitch. Football’s importance, Isaacs said, was enhanced by its force as a provider of human emotions in an emotionally neutral context.

Isaacs pointed out that the only positive effects of long prison sentences is that they can strengthen prisoners’ organizational skills and improve their understanding of human nature. The activities of the Makana FA reinforced this outcome. Intriguingly, both candidates for the ANC presidency in 2012, South African President Jacob Zuma and his challenger Kgalema Motlanthe, played football on Robben Island. “If it had not been for the beautiful game and these community building devices,” Isaacs concluded, “we could have become psychological and physical wrecks incapable of integration into a multicultural world, let alone be able to contribute positively to it.” May you rest in peace Sedick Isaacs. An exemplary South African who can teach folks in Mangaung and at SAFA a few lessons about doing the right thing in politics and football.