Thirty years ago, on May 29, 1985, I gathered with a dozen teammates in a living room in Rome to watch the European Cup final between my Juventus and Liverpool. Barely fifteen years old, black-and-white scarf around my neck, there was nothing more I wanted than to avenge our shocking loss to Hamburg in the final two years earlier.

There was reason to be moderately optimistic, partly because four months earlier we had beaten Liverpool 2-0 (Boniek 39′, 79′) to claim the 1984 European Super Cup.

Forty-five minutes or so before the scheduled kickoff in Brussels, I took my seat on the floor. A perfectly unobstructed view of the television screen. Within minutes, disturbing images of chaos at the run down Heysel Stadium started beaming in.

The voice of Bruno Pizzul, a kind of Martin Tyler of Italian football, conveyed bewildering news. Something terrible was unfolding. Death at the stadium? We switched on the radio. Confusion.

Then, slowly, an accumulation of anecdotal reports led to confirmation of an unspeakable tragedy: 36 people were dead (a figure later revised to 39). Almost all Juventus fans. Men, women, and children killed in a stampede and wall collapse in the corner Z sector as they fled a charge by Liverpool supporters.

My heart was in my throat.

Tag: UEFA

The 2015 African Nations Cup begins on January 17 in Equatorial Guinea. The oil-rich dictatorship, a former Spanish colony with a population of 736,000, agreed to host the tournament on short notice after Morocco pulled out due to fears related to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

Africa’s most important tournament is organized by the Confederation of African Football (CAF), a trailblazing pan-Africanist institution born at the dawn of the era of decolonization. Joining the world body, as I’ve written elsewhere, was an honorable, quick, and inexpensive way for newly independent nations to assert their full membership in the international community.

CAF took tangible shape at the 1956 FIFA Congress in Lisbon. There, delegates from Egypt, Sudan, and South Africa convened to draft a constitution and by-laws. The men also decided to organize a continental championship. Ethiopia was also involved in the discussions, but Yidnecatchew Tessema was unable to travel to Lisbon. The African proposal was later sent to FIFA for review and approval (see image at left).

On February 8, 1957, football officials from Sudan, Egypt, Ethiopia, and South Africa convened at Khartoum’s Grand Hotel to formally launch CAF. Fred Fell, a white man representing apartheid South Africa, was invited because his country was a member of FIFA and the Africans did not wish to be perceived as undiplomatic. In the meantime, the white South African football association gingerly debated the composition of the national team. However, the authorities Pretoria opposed a mixed selection and the white football establishment did not challenge the policy.

There are conflicting accounts about what happened next. CAF officials stated that they promptly excluded South Africa in a show of unequivocal pan-African solidarity. Fell and white South African football put forward a different story: they claimed they withdrew the team prior to any sanctions due to the team’s impending tour to Europe as well as security concerns linked to the ongoing Suez Crisis. Unfortunately, the minutes of the meeting at CAF were later destroyed in a fire so we may never know the exact truth of the matter. What is certain is that the South African issue did not disappear. To the contrary, the struggle against apartheid in football would become a powerful bond that united CAF and nearly all African nations for three decades.

South Africa’s absence in 1957 meant that only three teams, comprised of amateurs, participated in the inaugural African Nations Cup. Ethiopia, which had been drawn to play against South Africa, received a bye into the final. Egypt defeated hosts Sudan 2–1 and then dispatched Ethiopia 4–0 in the final watched by a crowd of 30,000 at the Stade Municipal. All four goals were scored by striker Mohammed Diab El-Attar “Ad Diba.” “Those were unforgettable matches,” Ad Diba recalled in an interview in 2001. “The success of this championship and its popularity amongst the Sudanese encouraged the African federation to organize a tournament on a biennial basis and to be played in a different country each time,” he said. Ad Diba made history again eleven years later in Addis Ababa, when he refereed the Afcon final between Congo (DRC) and Ghana (see video).

In those early days, CAF brought to life Kwame Nkrumah’s dream of a United States of Africa. At the same time, football provided a rare form of national culture, unity, and pride in postcolonial Africa.

Today, the African Nations Cup has transformed itself into a globalized commercial event with multinational corporate sponsors, matches on satellite television and online, many European coaches, and most players on the sixteen squads employed by European clubs. It is a far cry from 1957. And yet an alluring contradiction has endured: the Afcon showcases Pan-African solidarity while triggering 90-minute nationalism.

Tomorrow’s Champions League final between Chelsea and Bayern Munich seems promising, even for neutrals like me. The Bavarians are at home, but Chelsea are currently in better form. In an intriguing twist, Chelsea have four players suspended, Bayern three, “which means any assessment of what might happen is going to be dotted with ifs and maybes” writes Jonathan Wilson in his SI.com column.

So let’s play every armchair manager’s favorite fun game. My prediction: Chelsea 2, Bayern 1, possibly after extra time. Goalscorers: Drogba, Mata, and Robben.

What’s your prediction?

UEFA bans vuvuzelas

UEFA announced that vuvuzelas will not be permitted in European stadia hosting UEFA competitions. ‘The magic of football consists of the two-way exchange of emotions between the pitch and the stands, where the public can transmit a full range of feelings to the players,’ explained the European confederation’s web site. ‘However, UEFA is of the view that the vuvuzelas would completely change the atmosphere, drowning supporter emotions and detracting from the experience of the game.’

Curbing fans’ freedom to express themselves is generally not my cup of tea, but maybe these self-interested football technocrats are helping to preserve what’s left of stadium soundscapes and our hearing.

Click here to read the UEFA statement.

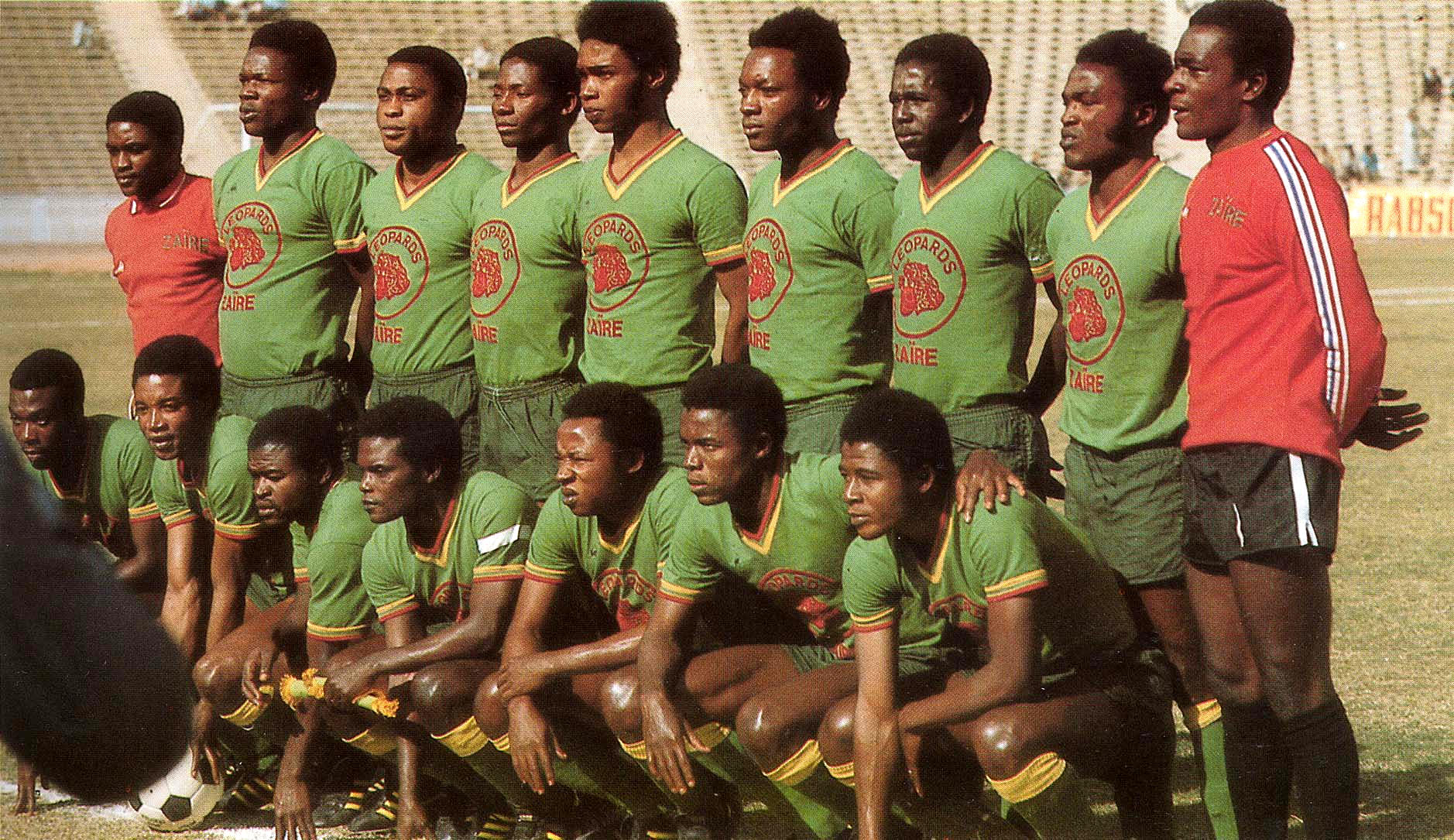

(Insert above. Zaire, Africa’s only representative in the 1974 World Cup Finals.)

(Please be aware the following is classic football anorak commentary. Davy considers how UEFA can best re calibrate its representation in future World Cups.)

Thirteen European nations will materialize in South Africa in 2010. Many deservedly so. Only five African nations will join them. I expect after the performances of Africa’s representatives, demand for a fairer apportioning of places in future World Cups will be irresistible and undeniable.

The fat is in the UEFA zone, as are the bigger television audiences and mobile credit card carrying supporters. Trimming UEFA representation in future World Cups could be a gristly experience. Asia and the Americas have sound claims also.