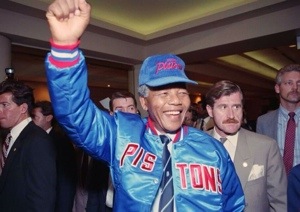

Sport is serious fun. Nelson Mandela, a keen amateur boxer in his youth, appreciated how the antiapartheid sport boycott assisted South Africa’s liberation struggle and, as a democratically elected president, he used the “politics of pleasure” to propel Rainbow Nationalism. Team sports like football reveal much about the experiences and mindsets of neighborhoods, cities, and nations. “The way we play the game, organize it and reward it reflects the kind of community we are,” is how Arthur Hopcraft put it in The Football Man (1968), one of the finest football books ever written.

Sport is serious fun. Nelson Mandela, a keen amateur boxer in his youth, appreciated how the antiapartheid sport boycott assisted South Africa’s liberation struggle and, as a democratically elected president, he used the “politics of pleasure” to propel Rainbow Nationalism. Team sports like football reveal much about the experiences and mindsets of neighborhoods, cities, and nations. “The way we play the game, organize it and reward it reflects the kind of community we are,” is how Arthur Hopcraft put it in The Football Man (1968), one of the finest football books ever written.

These issues strike at the heart of a new project I am embarking on with my Latin Americanist colleague Brenda Elsey, author of a splendid book on fútbol and politics in Chile. Brenda and I will be editing a special issue of Radical History Review on “Historicizing the Politics and Pleasure of Sport.” This marks the first time RHR, an academic journal known for “addressing issues of gender, race, sexuality, imperialism, and class, and stretching the boundaries of historical analysis to explore Western and non-Western histories” will turn its attention to sport. The issue is scheduled for publication in 2016.

Here’s the call for papers:

The global reach of football (soccer), basketball, cricket, and Olympic sports in the contemporary world can be traced back to European and U.S. imperial and commercial expansion. The agents of that imperialism—teachers, soldiers, traders, and colonial officials— believed sport to be an important part of their “civilizing mission.” Military interventions in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, often accompanied by “soft power” cultural programs and private business ventures, fueled the popularity of Western sports. Reform movements tied eugenics and racism to their dissemination. But local elites and subalterns were not simply duped; they enjoyed the games on their own terms. As more communities participated, sport came to represent and constitute broader processes of social change. In the stands, sports pages, and clubhouses, fans rendered sport a place to debate racial and gender hierarchies. In the late twentieth century, international sport became part of a new global capitalist network of sport institutions (e.g. FIFA, International Olympic Committee, International Cricket Council), private corporations, mass media, and migrant athletes and coaches. In this process, sport came to symbolize and intensify unequal social and economic relations.

Histories of sport reveal a paradox: sport generates empowerment and disempowerment; inclusion and exclusion; unity and division. Sports have provided spaces for pleasure, freedom, solidarity, and resistance, but they have also reproduced class privilege, patriarchy, and racism. The performance of masculinities, creation of ideal body types, and the ongoing marginalization of women in sport illustrate these tensions. Recent events in Brazil, where controversy over contemporary mega sporting events merged with massive demonstrations for a range of social justice issues, highlight the unusual capacity of sport both to crystallize inequalities and to trigger civic activism. Reports of labor abuses in Qatar and censorship and environmental damage in Russia cast a dark shadow on the human and material costs of hosting “mega” sports events.

The editors invite submissions from scholars working on any period and world region. We are especially interested in studies that build upon the rich historiography about the nature of agency, identity, and embodiment as a way to explore sport’s contradictory past and present.

Possible topics include, but are not limited to:

– Sport, nationalism, and internationalism

– Sport, the public sphere, and citizenship

– Sport and radical protest

– Race, ethnicity, and “color lines” in sport

– Sport, reactionary politics, and racism

– Fan cultures, youth, consumption, and solidarity (including fan violence)

– Historicizing playing styles, aesthetics, and physical movement

– Histories of bodies, gender, and sexuality (including women’s athletics, masculinities, heteronormativity, queering of sports)

– Sport and the Global South (including sport migration, neocolonialism)

– Histories of Disability/Ability in sports

– Histories of illicit sport, gambling, and doping

– Revisiting landmark works, such as C. L. R. James’s Beyond a Boundary (1963)

– Sport and the Cold War

– The Sporting Press

– Sport-Media-Tourism Complex and mega events

– Stadiums as sites of political struggle, urban geopolitics, and the spaces of sport

– Processes of professionalization and relationships to amateurism

– Historiographies, methodologies, and sourcing of sport studies

The RHR seeks scholarly, monographic research articles, but we also encourage such non-traditional contributions as photo essays, film and book review essays, interviews, brief interventions, “conversations” between scholars and/or activists, and teaching notes and annotated course syllabi for our Teaching Radical History section. Preliminary inquiries can be sent to Peter Alegi (alegi AT msu.edu), Brenda Elsey (Brenda.elsey AT hofstra.edu), and Amy Chazkel (amy.chazkel AT qc.cuny.edu).

Procedures for submission of articles: At this time we are requesting abstracts that are no longer than 400 words; these are due by September 1, 2014 and should be submitted electronically as an attachment to contactrhr@gmail.com with “Issue 125 submission” in the subject line. By October 15, 2014, authors will be notified whether they should submit a full version of their article to undergo the peer review process. The due date for completed drafts of articles is February 1, 2015. An invitation to submit a full article does not guarantee publication; publication depends on the peer review process and the overall shape the journal issue will take.

Please send any images as low-resolution digital files embedded in a Word document along with the text. If chosen for publication, you will need to send high-resolution image files (jpg or tif files at a minimum of 300 dpi), and secure written permission to reprint all images. Authors must also secure permissions for sound clips that they may wish to include with their articles in the online version of the journal. Those articles selected for publication after the peer review process will be included in issue 125 of Radical History Review, scheduled to appear in Spring 2016.

Abstract Deadline: September 1, 2014

contactrhr AT gmail.com